A supervolcano is a large volcano that has had an eruption with a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 8, the largest recorded value on the index. This means the volume of deposits for that eruption is greater than 1,000 cubic kilometers.

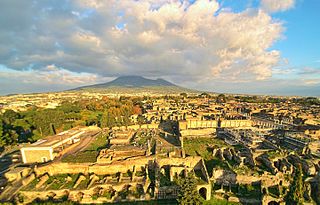

Mount Vesuvius is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes which form the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier and originally much higher structure.

Bradyseism is the gradual uplift or descent of part of the Earth's surface caused by the filling or emptying of an underground magma chamber and/or hydrothermal activity, particularly in volcanic calderas. It can persist for millennia in between eruptions and each uplift event is normally accompanied by thousands of small to moderate earthquakes. The word derives from the ancient Greek words "bradus", meaning 'slow', and "seism" meaning 'movement', and was coined by Arturo Issel in 1883.

Mount Tarawera is the volcano responsible for one of New Zealand's largest historic eruptions. Located 24 kilometres southeast of Rotorua in the North Island, it consists of a series of rhyolitic lava domes that were fissured down the middle by an explosive basaltic eruption in 1886, which killed an estimated 120 people. These fissures run for about 17 kilometres northeast-southwest.

A volcano tectonic earthquake is an earthquake induced by the movement of magma. The movement results in pressure changes in the rock around where the magma has experienced stress. At some point, the rock may break or move. The earthquakes may also be related to dike intrusion and may occur as earthquake swarms. An example is the 2007–2008 Nazko earthquake swarm in central British Columbia, Canada.

Galeras is an Andean stratovolcano in the Colombian department of Nariño, near the departmental capital Pasto. Its summit rises 4,276 metres (14,029 ft) above sea level. It has erupted frequently since the Spanish conquest, with its first historical eruption being recorded on December 7, 1580. A 1993 eruption killed nine people, including six scientists who had descended into the volcano's crater to sample gases and take gravity measurements in an attempt to be able to predict future eruptions. It is currently the most active volcano in Colombia.

Porak or Axarbaxar is a stratovolcano located in the Vardenis volcanic ridge. It lies about 20 km (12 mi) southeast of Lake Sevan and the volcanic field spans the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan (NKR) with lava flows running into both countries. Ten satellite cones and fissure vents lie on the flanks of the volcano.

Morne Diablotins is the highest mountain in Dominica, an island-nation in the Caribbean Lesser Antilles. It is the second highest mountain in the Lesser Antilles, after La Grande Soufrière in Guadeloupe. Morne Diablotins is located in the northern interior of the island, about 15 miles north of Dominica's capital Roseau and about 6 miles southeast of Portsmouth, the island's second-largest town. It is located within Morne Diablotin National Park.

George Patrick Leonard Walker was a British geologist who specialized in mineralogy and volcanology.

Mount Hasan is a volcano in Anatolia, Turkey. It has two summits, the 3,069 metres (10,069 ft) high eastern Small Hasan Dagi and the 3,253 metres (10,673 ft) high Big Hasan Dagi, and rises about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) above the surrounding terrain. It consists of various volcanic deposits, including several calderas, and its activity has been related to the presence of several faults in the area and to regional tectonics.

Somma Vesuviana is a town and comune in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, southern Italy.

Laguna de Ayarza is a crater lake in Guatemala. The lake is a caldera that was created some 20,000 years ago by a catastrophic eruption that destroyed a twinned volcano and blanketed the entire region with a layer of pumice. The lake has a surface area of 14 km² and a maximum depth of 230 m. The lake has a surface elevation of 1409 m.

The 1703 Apennine earthquakes were a sequence of three earthquakes of magnitude ≥6 that occurred in the central Apennines of Italy, over a period of 19 days. The epicenters were near Norcia, Montereale and L'Aquila, showing a southwards progression over about 36 km. These events involved all of the known active faults between Norcia and L'Aquila. A total of about 10,000 people are estimated to have died as a result of these earthquakes, although because of the overlap in areas affected by the three events, casualty numbers remain highly uncertain.

The magma supply rate measures the production rate of magma at a volcano. Global magma production rates on Earth are about 20–25 cubic kilometres per year (4.8–6.0 cu mi/a).

Dispersal index is a parameter in volcanology. The dispersal index was defined by George P. L. Walker in 1973 as the surface area covered by an ash or tephra fall, where the thickness is equal or more than 1/100 of the thickness of the fall at the vent. An eruption with a low dispersal index leaves most of its products close to the vent, forming a cone; an eruption with a high dispersal index forms thinner sheet-like deposits which extends to larger distances from the vent. A dispersal index of 500 square kilometres (190 sq mi) or more of coarse pumice is one proposed definition of a Plinian eruption. Likewise, a dispersal index of 50,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi) has been proposed as a cutoff for an ultraplinian eruption. The definition of 1/100 of the near-vent thickness was partially dictated by the fact that most tephra deposits are not well preserved at larger distances.

The geology of Martinique originated from volcanic eruptions, but has different rocks than nearby Lesser Antilles volcanic island arc islands all of which formed in the last 40 million years in the Cenozoic. A high-alumina basalt ranges from olivine basalt to tridymite-rich dacite. Calc-alkaline volcanic rocks are rich in hornblende and orthpyroxene andesite, hornblende andesite and quartz-hornblende dacite are also common. Mount Pelee is one of the most active Caribbean volcanoes with 20 eruptions in the last 5000 years. It also heats groundwater, generating hydrothermal eruptions at sulfur springs in 1751 and 1851.