Emma Goldman was a Lithuanian-born anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the 20th century.

Anarchist communism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and the distribution of resources "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Anarchism and violence have been linked together by events in anarchist history such as violent revolution, terrorism, assassination attempts and propaganda of the deed. Propaganda of the deed, or attentát, was espoused by leading anarchists in the late 19th century and was associated with a number of incidents of political violence. Anarchist thought, however, is quite diverse on the question of violence. Where some anarchists have opposed coercive means on the basis of coherence, others have supported acts of violent revolution as a path toward anarchy. Anarcho-pacifism is a school of thought within anarchism which rejects all violence.

Sam Dolgoff was an anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist from Russia who grew up, lived and was active in the United States.

Marie Louise Berneri was an anarchist activist and author. Born in Italy, she spent much of her life in Spain, France, and England. She was involved with the short-lived publication, Revision, with Luis Mercier Vega and was a member of the group that edited Revolt, War Commentary, and the newspaper Freedom. She was a continuous contributor to Spain and the World. She also wrote a survey of utopias, Journey Through Utopia, first published in 1950 and re-issued in 2020. Neither East Nor West is a selection of her writings (1952).

Charlotte Mary Wilson was an English Fabian and anarchist who co-founded Freedom newspaper in 1886 with Peter Kropotkin, and edited, published, and largely financed it during its first decade. She remained editor of Freedom until 1895.

Anarchism in Russia developed out of the populist and nihilist movements' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

The Manifesto of the Sixteen, or Proclamation of the Sixteen, was a document drafted in 1916 by eminent anarchists Peter Kropotkin and Jean Grave which advocated an Allied victory over Germany and the Central Powers during the First World War. At the outbreak of the war, Kropotkin and other anarchist supporters of the Allied cause advocated their position in the pages of the Freedom newspaper, provoking sharply critical responses. As the war continued, anarchists across Europe campaigned in anti-war movements and wrote denunciations of the war in pamphlets and statements, including one February 1916 statement signed by prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman and Rudolf Rocker.

Marie Le Compte was an American journal editor and anarchist who was active during the early 1880s.

Maria Isidorovna Goldsmith, also known as Marie Goldsmith, was a Russian Jewish anarchist and collaborator of Peter Kropotkin. She also wrote under the pseudonyms Maria Isidine and Maria Korn.

The Anarchist Prince is a biography of Peter Kropotkin by George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumović.

Anarchist Portraits is a 1988 history book by Paul Avrich about the lives and personalities of multiple prominent and inconspicuous anarchists.

Memoirs of a Revolutionist is Peter Kropotkin's autobiography and his most famous work.

Moshe Katz (1864–1941) was an American Jewish editor and activist. He was a central figure of New York City's Jewish anarchist circle at the turn of the century, participating with the Pioneers of Liberty and giving speeches. He briefly edited the Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper Fraye Arbeter Shtime in the 1890s and contributed to other Yiddish-language periodicals. Katz translated multiple anarchist classics into Yiddish: Conquest of Bread, Moribund Society and Anarchy, and Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist. He grew towards Labor Zionism after the 1903 anti-Jewish Kishinev pogrom and eventually moved to Philadelphia to launch and edit a Yiddish daily periodical, Di Yiddishe velt, for twenty years beginning in 1914. Katz brought his New York literary contacts to the Philadelphia paper with content that rivaled the Yiddish periodicals of New York.

Boleslav Kazimirovich Kukel was a Russian general, Governor of Transbaikalia, officially "the chief of General Staff of East Siberia," a geologist and geographer, and a Lithuanian strongly inspired with the modern ideas of the epoch, who maintained personal connections to various Russian radical political figures exiled to Siberia.

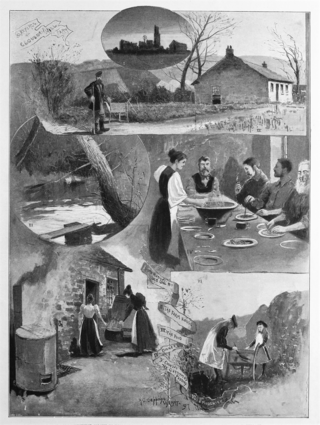

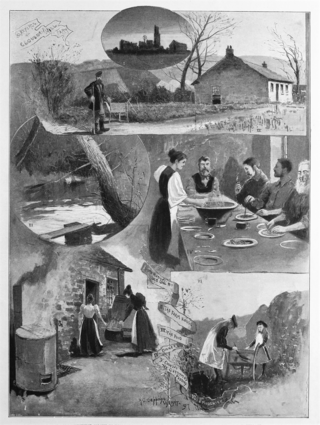

Clousden Hill Free Communist and Co-operative Colony was an anarcho-communist commune from 1895 until 1898 in Forest Hall, North Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England. The commune was part of the back-to-the-land movement, operating a 12-acre farm under collective ownership and democratic control.

The Libertarian Book Club and Libertarian League were two postwar anarchist groups in New York City associated with Sam and Esther Dolgoff.

The Great French Revolution, 1789–1793 is a 1909 history of the French Revolution by Peter Kropotkin, published in both French and English. It was first translated from French to English by William Heinemann in 1909.