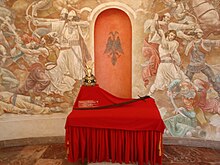

The coat of arms of Albania is an adaptation of the flag of Albania and is based on the symbols of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. It features the black double-headed eagle, documented in official use since 1458, as evidenced from a sealed document uncovered in the Vatican Secret Archive, addressed to Pope Pius II and co-sealed by notary Johannes Borcius de Grillis. The stylized gold helmet is partially based on the model of crown-like rank that once belonged to Skanderbeg, currently on display at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, first mentioned in 1593 in the Ambras armory inventory and depicted in 1601/03 in the "Armamentarium Heroicum" of Jakob Schrenck von Notzing. The ruler of Austria, Ferdinand II, acquired the helmet from the Duke of Urbino, so mentioned in a letter sent to him from the duke, dated 15 October 1578.

The League of Lezhë, also commonly referred to as the Albanian League, was a military and diplomatic alliance of the Albanian aristocracy, created in the city of Lezhë on 2 March 1444. The League of Lezhë is considered the first unified independent Albanian country in the Medieval age, with Skanderbeg as leader of the regional Albanian chieftains and nobles united against the Ottoman Empire. Skanderbeg was proclaimed "Chief of the League of the Albanian People," while Skanderbeg always signed himself as "DominusAlbaniae".

The Battle of Albulena, also known as the Battle of Ujëbardha, was fought on 2 September 1457 between Albanian forces led by Skanderbeg and an Ottoman army under Isak bey Evrenoz and Skanderbeg's nephew, Hamza Kastrioti.

The Arianiti were an Albanian noble family that ruled large areas in Albania and neighbouring areas from the 11th to the 16th century. Their domain stretched across the Shkumbin valley and the old Via Egnatia road and reached east to today's Bitola.

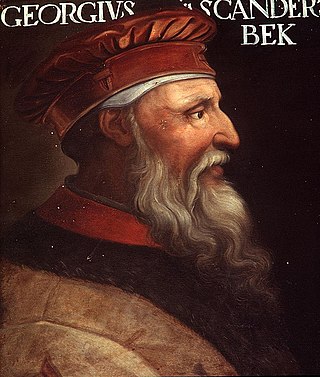

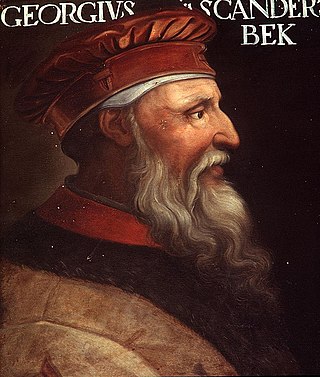

Gjergj Kastrioti, commonly known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanian feudal lord and military commander who led a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania, North Macedonia, Greece, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Serbia.

The Progoni were an Albanian noble family which established the first Albanian state in recorded history, the Principality of Arbanon.

Demetrio Progoni was an Albanian leader who ruled as Prince of the Albanians from 1208 to 1216 the Principality of Arbanon, the first Albanian state. He was the successor and brother of Gjin Progoni and their father, Progon of Kruja. Following the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in the Fourth Crusade, he managed to further secure the independence of Arbanon and extended its influence to its maximum height. Throughout much his rule he was in struggle against the Republic of Venice, Zeta of Đorđe Nemanjić and later the Despotate of Epiros and inversely, maintained good relations with their rivals, the Republic of Ragusa, and at first Stefan Nemanjić of Raška, whose daughter Komnena he married. The Gëziq inscription found in the Catholic church of Ndërfandë shows that by the end of his life he was a Catholic. In Latin documents, of the time, he is often styled as princeps Arbanorum and in Byzantine documents as megas archon and later as Panhypersebastos. Under increasing pressure from the Despotate of Epiros, his death around 1216 marks the end of Arbanon as a state and the beginning of a period of autonomy until its final ruler Golem of Kruja joined the Nicaean Empire. The annexation sparked the Rebellion of Arbanon in 1257. He didn't have any sons to continue his dynasty, but his wealth and a part of his domain in Mirdita passed after Demetrio's death to his underage nephew, Progon, whom he named protosevastos. The Dukagjini family which appeared in historical record 70 years later in the same region may have been relatives or direct descendants of the Progoni.

The Battle of Torvioll, also known as the Battle of Lower Dibra, was fought on 29 June 1444 on the Plain of Torvioll, in what is modern-day Albania. Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg was an Ottoman Albanian general who decided to go back to his native land and take the reins of a new Albanian League against the Ottoman Empire. He, along with 300 other Albanians fighting at the Battle of Niš, deserted the Ottoman army to head towards Krujë, which fell quickly through a subversion. He then formed the League of Lezhë, a confederation of Albanian princes united in war against the Ottoman Empire. Murad II, realizing the threat, sent one of his most experienced captains, Ali Pasha, to crush the new state with a force of 25,000-40,000 men.

The Principality of Kastrioti was one of the Albanian principalities during the Late Middle Ages. It was formed by Pal Kastrioti who ruled it until 1407, after which his son, Gjon Kastrioti ruled until his death in 1437 and then ruled by the national hero of Albania, Skanderbeg.

Andronika Arianiti, also known as Donika Kastrioti, was an Albanian noblewoman and the spouse of Albanian leader and national hero Skanderbeg. She was the daughter of Gjergj Arianiti, an earlier leader in the ongoing revolt against the Ottomans.

The Albanian–Venetian War of 1447–48 was waged between Venetian and Ottoman forces against the Albanians under George Kastrioti Skanderbeg. The war was the result of a dispute between the Republic and the Dukagjini family over the possession of the Dagnum fortress. Skanderbeg, then ally of the Dukagjini family, moved against several Venetian held towns along the Albanian coastline, in order to pressure the Venetians into restoring Dagnum. In response, the Republic sent a local force to relieve the besieged fortress of Dagnum, and urged the Ottoman Empire to send an expeditionary force into Albania. At that time the Ottomans were already besieging the fortress of Svetigrad, stretching Skanderbeg's efforts thin.

The siege of Svetigrad or Sfetigrad began on 14 May 1448 when an Ottoman army, led by Sultan Murad II, besieged the fortress of Svetigrad. After the many failed Ottoman expeditions into Albania against the League of Lezhë, a confederation of Albanian Principalities created in 1444 and headed by Skanderbeg, Murad II decided to march an army into Skanderbeg's dominions in order to capture the key Albanian fortress of Svetigrad. The fortress lay on an important route between present-day North Macedonia and Albania, and thus its occupation would give the Ottomans easy access into Albania.

Gjon II Kastrioti, was the son of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero, and of Donika Kastrioti, daughter of the powerful Albanian prince, Gjergj Arianiti. He was for a short time Lord of Kruja after his father's death, then Duke of San Pietro in Galatina (1485), Count of Soleto, Signore of Monte Sant'Angelo and San Giovanni Rotondo. In 1495, Ferdinand I of Naples gave him the title of the Signore of Gagliano del Capo and Oria. While in his teens, he was forced to leave the country after the death of his father in 1468. He is known also for his role in the Albanian Uprisings of 1481, when, after reaching the Albanian coast from Italy, settling in Himara, he led a rebellion against the Ottomans. In June 1481, he supported forces of Ivan Crnojević to successfully recapture Zeta from the Ottomans. He was unable to re-establish the Kastrioti Principality and liberate Albania from the Ottomans, and he retired in Italy after three years of war in 1484.

Vladan Gjurica was an Albanian nobleman and Skanderbeg's main advisor during Skanderbeg's rebellion. He is thought to be from Gjoricë, in modern-day Dibër County from which he got the surname Gjurica/Jurica. He was most likely a member of the Arianiti family. During the Battle of Vaikal he was captured and sent to Constantinople where he was skinned alive.

The Jonima were a noble Albanian family that held a territory around Lezhë, as vassals of Arbanon, Serbia and Ottoman Empire, active in the 13th to 15th centuries. The Jonima, like most Albanian noble families, were part of a fis or clan. It is also said that they had close ties to the Kastrioti family.

Dhimitër Jonima was an Albanian nobleman from the Jonima family. He initially resisted the Ottomans - namely at the Battle of Kosovo - before becoming their vassal, and he eventually switched to become a vassal of Venice. He was the lord of the lands that encompassed the trade route from Lezhë to Prizren, holding possessions between Lezhë and Rrëshen.

The Spani were a noble Albanian family that emerged in the 14th century. They owned large estates in and around the fortified town of Drivasto and in neighbouring Scutari. During the late 15th century, a faction of the family settled in Venetian territories, primarily Venice itself and Dalmatia.

Komnen Arianiti was an Albanian nobleman of the Arianiti family, who held an area in central Albania around Durrës. His son Gjergj became a prominent leader of the Albanian-Ottoman wars.

Skanderbeg's rebellion was an almost 25-year long anti-Ottoman rebellion led by the Albanian military commander Skanderbeg in what is today Albania and its neighboring countries. It was a rare successful instance of resistance by Christians during the 15th century and through his leadership led Albanians in guerrilla warfare against the Ottomans.

Stanisha Kastrioti was an Albanian nobleman, a member of the Kastrioti family, and older brother of Skanderbeg.