The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, the Famine and the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland lasting from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a historical social crisis and subsequently had a major impact on Irish society and history as a whole. The most severely affected areas were in the western and southern parts of Ireland—where the Irish language was dominant—and hence the period was contemporaneously known in Irish as an Drochshaol, which literally translates to "the bad life" and loosely translates to "the hard times". The worst year of the famine was 1847, which became known as "Black '47". During the Great Hunger, roughly 1 million people died and more than 1 million more fled the country, causing the country's population to fall by 20–25% between 1841 and 1871. Between 1845 and 1855, at least 2.1 million people left Ireland, primarily on packet ships but also on steamboats and barques—one of the greatest exoduses from a single island in history.

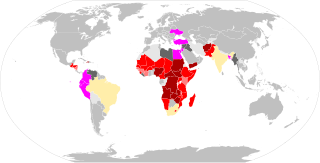

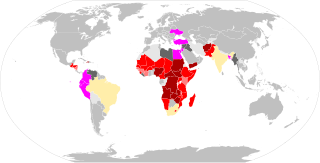

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several possible factors, including war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every inhabited continent in the world has experienced a period of famine throughout history. During the 19th and 20th century, Southeast and South Asia, as well as Eastern and Central Europe, suffered the greatest number of fatalities. Deaths caused by famine declined sharply beginning in the 1970s, with numbers falling further since 2000. Since 2010, Africa has been the most affected continent in the world by famine.

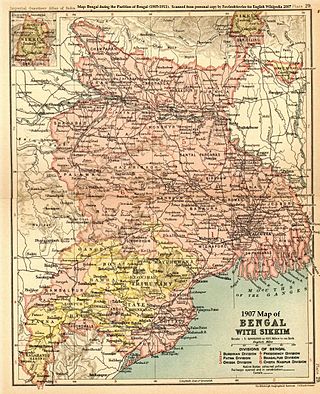

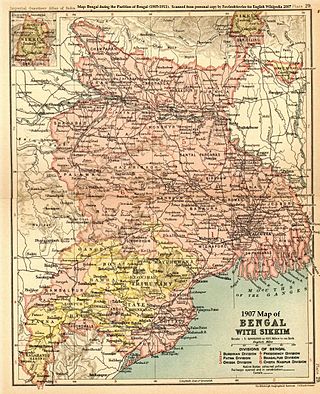

The Ganges Delta is a river delta in Eastern South Asia predominantly covering the Bengal region of the subcontinent, consisting of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. It is the world's largest river delta and it empties into the Bay of Bengal with the combined waters of several river systems, mainly those of the Brahmaputra river and the Ganges river. It is also one of the most fertile regions in the world, thus earning the nickname the Green Delta. The delta stretches from the Hooghly River east as far as the Meghna River.

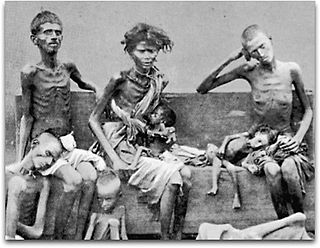

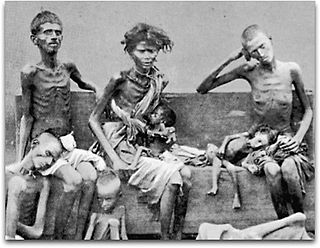

The Bengal famine of 1943 was an anthropogenic famine in the Bengal province of British India during World War II. An estimated 0.8–3.8 million people died, in the Bengal region, from starvation, malaria and other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions and lack of health care. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and catastrophically disrupted the social fabric. Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the British Indian Army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or other large cities in search of organised relief.

The Vietnamese famine of 1945 was a famine that occurred in northern Vietnam in French Indochina during World War II from October 1944 to late 1945, which at the time was under Japanese occupation from 1940 with Vichy France as an ally of Nazi Germany in Western Europe. Between 400,000 and 2 million people are estimated to have starved to death during this time.

Famine scales are metrics of food security going from entire populations with adequate food to full-scale famine. The word "famine" has highly emotive and political connotations and there has been extensive discussion among international relief agencies offering food aid as to its exact definition. For example, in 1998, although a full-scale famine had developed in southern Sudan, a disproportionate amount of donor food resources went to the Kosovo War. This ambiguity about whether or not a famine is occurring, and the lack of commonly agreed upon criteria by which to differentiate food insecurity has prompted renewed interest in offering precise definitions. As different levels of food insecurity demand different types of response, there have been various methods of famine measurement proposed to help agencies determine the appropriate response.

Famine had been a recurrent feature of life in the South Asian subcontinent countries of India and Bangladesh, most notoriously under British rule. Famines in India resulted in millions of deaths over the course of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Famines in British India were severe enough to have a substantial impact on the long-term population growth of the country in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Great Bengal famine of 1770 was a famine that struck Bengal and Bihar between 1769 and 1770 and affected some 30 million people. It occurred during a period of dual governance in Bengal. This existed after the East India Company had been granted the diwani, or the right to collect revenue, in Bengal by the Mughal emperor in Delhi, but before it had wrested the nizamat, or control of civil administration, which continued to lie with the Mughal governor, the Nawab of Bengal Nazm ud Daula (1765-72).

The North Korean famine, also known as the Arduous March or the March of Suffering, was a period of mass starvation together with a general economic crisis from 1994 to 1998 in North Korea. During this time there was an increase in defection from North Korea which peaked towards the end of the famine period.

Agriculture is the largest employment sector in Bangladesh, making up 14.2 percent of Bangladesh's GDP in 2017 and employing about 42.7 percent of the workforce. The performance of this sector has an overwhelming impact on major macroeconomic objectives like employment generation, poverty alleviation, human resources development, food security, and other economic and social forces. A plurality of Bangladeshis earn their living from agriculture. Due to a number of factors, Bangladesh's labour-intensive agriculture has achieved steady increases in food grain production despite the often unfavorable weather conditions. These include better flood control and irrigation, a generally more efficient use of fertilisers, as well as the establishment of better distribution and rural credit networks.

The European potato failure was a food crisis caused by potato blight that struck Northern and Western Europe in the mid-1840s. The time is also known as the Hungry Forties. While the crisis produced excess mortality and suffering across the affected areas, particularly affected were the Scottish Highlands, with Highland Potato Famine and, even more harshly, Ireland, which experienced Great Famine. Many people starved due to lack of access to other staple food sources.

The Orissa famine of 1866 affected the east coast of India from Madras northwards, an area covering 180,000 miles and containing a population of 47,500,000; the impact of the famine, however, was greatest in the region of Orissa, now Odisha, which at that time was quite isolated from the rest of India. In Odisha, the total number who died as a result of the famine was at least a million, roughly one third of the population.

The Doji bara famine of 1791–1792 in the Indian subcontinent was brought on by a major El Niño event lasting from 1789–1795 and producing prolonged droughts. Recorded by William Roxburgh, a surgeon with the British East India Company, in a series of pioneering meteorological observations, the El Niño event caused the failure of the South Asian monsoon for four consecutive years starting in 1789.

The Indian famine of 1899–1900 began with the failure of the summer monsoons in 1899 over Western and Central India and, during the next year, affected an area of 476,000 square miles (1,230,000 km2) and a population of 59.5 million. The famine was acute in the Central Provinces and Berar, the Bombay Presidency, the minor province of Ajmer-Merwara, and the Hissar District of the Punjab; it also caused great distress in the princely states of the Rajputana Agency, the Central India Agency, Hyderabad and the Kathiawar Agency. In addition, small areas of the Bengal Presidency, the Madras Presidency and the North-Western Provinces were acutely afflicted by the famine.

Bangladesh–Cuba relations refer to the bilateral relations between Bangladesh and Cuba. Relations between the two countries have been warm with both the countries putting their efforts to strengthen it further.

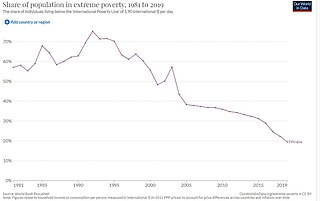

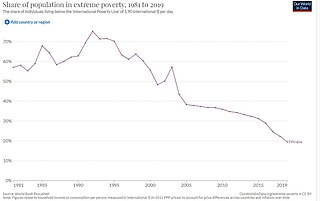

The African country of Ethiopia has made massive strides towards alleviating poverty since 2000 when it was assessed that their poverty rate was one of the greatest among all other countries. The country has made great strides in different areas of the Millennium Development Goals including eradicating various diseases and decreasing the rate of child mortality. Despite these improvements, poverty is still extremely high within the country. One of the leading factors in driving down poverty was the expansion of the agricultural sector. Poor farmers have been able to set higher food prices to increase their sales and revenue, but this expansion has come at a cost to the poorest citizens of the country, as they could not afford the higher priced food. One of the biggest challenges to alleviating this issue is changing the structure of Ethiopia's economy from an agricultural-based economy to a more industry-based economy. The current strategy for addressing poverty in Ethiopia is by building on existing government systems and development programs that are already in place within the country.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity has intensified in many places – in the second quarter of 2020 there were multiple warnings of famine later in the year. In an early report, the Nongovernmental Organization (NGO) Oxfam-International talks about "economic devastation" while the lead-author of the UNU-WIDER report compared COVID-19 to a "poverty tsunami". Others talk about "complete destitution", "unprecedented crisis", "natural disaster", "threat of catastrophic global famine". The decision of WHO on March 11, 2020, to qualify COVID as a pandemic, that is "an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people" also contributed to building this global-scale disaster narrative.

The 1992 famine in Somalia resulted from a severe drought and devastation caused by warring factions in southern Somalia, primarily the Somali National Front, in the fertile inter-riverine breadbasket between the Jubba and Shebelle rivers. The resulting famine primarily affected residents living in the riverine area, predominantly in Bay Region, and those internally displaced by the civil war.

During 2022 and 2023 there were food crises in several regions as indicated by rising food prices. In 2022, the world experienced significant food price inflation along with major food shortages in several regions. Sub-Saharan Africa, Iran, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Iraq were most affected. Prices of wheat, maize, oil seeds, bread, pasta, flour, cooking oil, sugar, egg, chickpea and meat increased. Causes included disruption of supply chains due to the COVID–19 pandemic, an energy crisis, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and significant floods and heatwaves in 2021 which destroyed key crops in the Americas and Europe. Droughts were also a factor; in early 2022, some areas of Spain and Portugal lost 60-80% of their crops due to widespread drought.

The premiership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman began on January 12 of 1972 when he was sworn in as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh after briefly serving as the President after returning from Pakistan's jail on January 10, 1972. He served as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh until January 25, 1975, for three years, and later led the parliament to adopt an amendment of the constitution that made him the President of Bangladesh, effectively for life.