Campaign finance laws in the United States have been a contentious political issue since the early days of the union. The most recent major federal law affecting campaign finance was the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, also known as "McCain-Feingold". Key provisions of the law prohibited unregulated contributions to national political parties and limited the use of corporate and union money to fund ads discussing political issues within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary election; However, provisions of BCRA limiting corporate and union expenditures for issue advertising were overturned by the Supreme Court in Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life.

In the United States, a political action committee (PAC) is a tax-exempt 527 organization that pools campaign contributions from members and donates those funds to campaigns for or against candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation. The legal term PAC was created in pursuit of campaign finance reform in the United States. Democracies of other countries use different terms for the units of campaign spending or spending on political competition. At the U.S. federal level, an organization becomes a PAC when it receives or spends more than $1,000 for the purpose of influencing a federal election, and registers with the Federal Election Commission (FEC), according to the Federal Election Campaign Act as amended by the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002. At the state level, an organization becomes a PAC according to the state's election laws.

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 is the primary United States federal law regulating political campaign fundraising and spending. The law originally focused on creating limits for campaign spending on communication media, adding additional penalties to the criminal code for election law violations, and imposing disclosure requirements for federal political campaigns. The Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on February 7, 1972.

A publicly funded election is an election funded with money collected through income tax donations or taxes as opposed to private or corporate funded campaigns. It is a policy initially instituted after Nixon for candidates to opt into publicly funded presidential campaigns via optional donations from tax returns. It is an attempt to move toward a one voice, one vote democracy, and remove undue corporate and private entity dominance.

OpenSecrets is a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. that tracks and publishes data on campaign finance and lobbying, including a revolving door database which documents the individuals who have worked in both the public sector and lobbying firms and may have conflicts of interest. It was created from the 2021 merger of the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) and the National Institute on Money in Politics (NIMP), both of which were organizations that tracked data on campaign finance in the United States and advocated for stricter regulation and disclosure of political donations.

Matching funds are funds that are set to be paid in proportion to funds available from other sources. Matching fund payments usually arise in situations of charity or public good. The terms cost sharing, in-kind, and matching can be used interchangeably but refer to different types of donations.

The financing of electoral campaigns in the United States happens at the federal, state, and local levels by contributions from individuals, corporations, political action committees, and sometimes the government. Campaign spending has risen steadily at least since 1990. For example, a candidate who won an election to the House of Representatives in 1990 spent on average $407,600, while the winner in 2022 spent on average $2.79 million; in the Senate, average spending for winning candidates went from $3.87 million to $26.53 million.

The Electoral Finance Act 2007 was a controversial act in New Zealand. The Fifth Labour Government introduced the Electoral Finance Bill partly in response to the 2005 New Zealand election funding controversy, in particular to "third-party" campaigns.

Political funding in Australia deals with political donations, public funding and other forms of funding received by politician or political party in Australia to pay for an election campaign. Political parties in Australia are publicly funded, to reduce the influence of private money upon elections, and subsequently, the influence of private money upon the shaping of public policy. After each election, the Australian Electoral Commission distributes a set amount of money to each political party, per vote received. For example, after the 2013 election, political parties and candidates received $58.1 million in election funding. The Liberal Party received $23.9 million in public funds, as part of the Coalition total of $27.2 million, while the Labor Party received $20.8 million.

Electoral reform in the United States refers to efforts to change American elections and the electoral system used in the United States.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States regarding campaign finance laws and free speech under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The court held 5–4 that the freedom of speech clause of the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting independent expenditures for political campaigns by corporations, nonprofit organizations, labor unions, and other associations.

The financing of federal political entities in Canada is regulated under the Canada Elections Act. A combination of public and private funds finances the activities of these entities during and outside of elections.

Political finance covers all funds that are raised and spent for political purposes. Such purposes include all political contests for voting by citizens, especially the election campaigns for various public offices that are run by parties and candidates. Moreover, all modern democracies operate a variety of permanent party organizations, e.g. the Democratic National Committee and the Republican National Committee in the United States or the Conservative Central Office and the Labour headquarters in the United Kingdom. The annual budgets of such organizations will have to be considered as costs of political competition as well. In Europe the allied term "party finance" is frequently used. It refers only to funds that are raised and spent in order to influence the outcome of some sort of party competition. Whether to include other political purposes, e.g. public relation campaigns by lobby groups, is still an unresolved issue. Even a limited range of political purposes indicates that the term "campaign funds" is too narrow to cover all funds that are deployed in the political process.

Political party funding is a method used by a political party to raise money for campaigns and routine activities. The funding of political parties is an aspect of campaign finance.

Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress—and a Plan to Stop It is the sixth book by Harvard law professor and free culture activist Lawrence Lessig. In a departure from the topics of his previous books, Republic, Lost outlines what Lessig considers to be the systemic corrupting influence of special-interest money on American politics, and only mentions copyright and other free culture topics briefly, as examples. He argued that the Congress in 2011 spent the first quarter debating debit-card fees while ignoring what he sees as more pressing issues, including health care reform or global warming or the deficit. Lessig has been described in The New York Times as an "original and dynamic legal scholar."

The term corporate donation refers to any financial contribution made by a corporation to another organization that furthers the contributor's own objectives. Two major kinds of such donations deserve specific consideration, charitable as well as political donations.

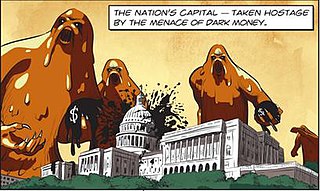

In politics, particularly the politics of the United States, dark money refers to spending to influence elections, public policy, and political discourse, where the source of the money is not disclosed to the public.

Political funding in New Zealand deals with political donations, public funding and other forms of funding received by politician or political party in New Zealand to pay for an election campaign. Only quite recently has political funding become an issue of public policy. Now there is direct and indirect funding by public money as well as a skeleton regulation of income, expenditure and transparency.

The American Anti-Corruption Act (AACA), sometimes shortened to Anti-Corruption Act, is a piece of model legislation designed to limit the influence of money in American politics by overhauling lobbying, transparency, and campaign finance laws. It was crafted in 2011 "by former Federal Election Commission chairman Trevor Potter in consultation with dozens of strategists, democracy reform leaders and constitutional attorneys from across the political spectrum," and is supported by reform organizations such as Represent.Us, which advocate for the passage of local, state, and federal laws modeled after the AACA. It is designed to limit or outlaw practices perceived to be major contributors to political corruption.

A number of measures have been suggested to improvise and strengthen the existing electoral practices in India.