Human cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices cannibalism is called a cannibal. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into zoology to describe animals consuming parts of individuals of the same species as food.

Cuauhtémoc, also known as Cuauhtemotzín, Guatimozín, or Guatémoc, was the Aztec ruler (tlatoani) of Tenochtitlan from 1520 to 1521, making him the last Aztec Emperor. The name Cuauhtemōc means "one who has descended like an eagle", and is commonly rendered in English as "Descending Eagle", as in the moment when an eagle folds its wings and plummets down to strike its prey. This is a name that implies aggressiveness and determination.

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves", or at Tamoanchan.

The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

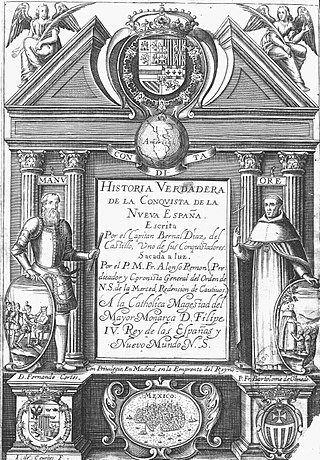

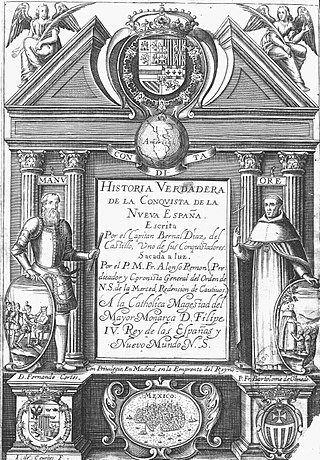

Bernal Díaz del Castillo was a Spanish conquistador who participated as a soldier in the conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and late in his life wrote an account of the events. As an experienced soldier of fortune, he had already participated in expeditions to Tierra Firme, Cuba, and to Yucatán before joining Cortés. In his later years he was an encomendero and governor in Guatemala where he wrote his memoirs called The True History of the Conquest of New Spain. He began his account of the conquest almost thirty years after the events and later revised and expanded it in response to the biography published by Cortés's chaplain Francisco López de Gómara, which he considered to be largely inaccurate in that it did not give due recognition to the efforts and sacrifices of others in the Spanish expedition.

Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España is a first-person narrative written in 1568 by military adventurer, conquistador, and colonist settler Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1492–1584), who served in three Mexican expeditions: those of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (1517) to the Yucatán peninsula; the expedition of Juan de Grijalva (1518); and the expedition of Hernán Cortés (1519) in the Valley of Mexico. The history relates his participation in the conquest of the Aztec Empire.

A tzompantli or skull rack was a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations, which was used for the public display of human skulls, typically those of war captives or other sacrificial victims. It is a scaffold-like construction of poles on which heads and skulls were placed after holes had been made in them. Many have been documented throughout Mesoamerica, and range from the Epiclassic through early Post-Classic. In 2015 archeologists announced the discovery of the Huey Tzompantli, with more than 650 skulls, in the archeological zone of the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

The Aztecs were a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican people of central Mexico in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. They called themselves Mēxihcah.

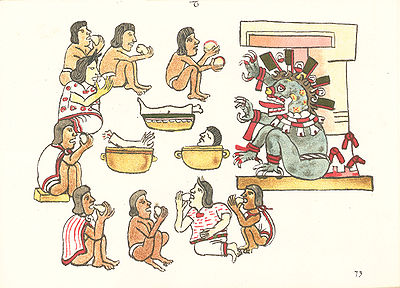

Human sacrifice was common in many parts of Mesoamerica, so the rite was nothing new to the Aztecs when they arrived at the Valley of Mexico, nor was it something unique to pre-Columbian Mexico. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Purépechas and Toltecs, and the Maya performed sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the Olmecs, and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. However, the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations. What distinguished Aztec practice from Maya human sacrifice was the way in which it was embedded in everyday life. These cultures also notably sacrificed elements of their own population to the gods.

Tlaxcala was a pre-Columbian city and state in central Mexico.

Aztec cuisine is the cuisine of the former Aztec Empire and the Nahua peoples of the Valley of Mexico prior to European contact in 1519.

Exocannibalism, as opposed to endocannibalism, is the consumption of flesh from humans that do not belong to one's close social group—for example, eating one's enemies. It has been interpreted as an attempt to acquire desired qualities of the victim and as "ultimate form of humiliation and domination" of a vanquished enemy in warfare. Such practices have been documented in various cultures, including the Aztecs in Mexico and the Caribs and Tupinambá in South America.

Tlatelolco was a pre-Columbian altepetl, or city-state, in the Valley of Mexico. Its inhabitants, known as the Tlatelolca, were part of the Mexica, a Nahuatl-speaking people who arrived in what is now central Mexico in the 13th century. The Mexica settled on an island in Lake Texcoco and founded the altepetl of Mexico-Tenochtitlan on the southern portion of the island. In 1337, a group of dissident Mexica broke away from the Tenochca leadership in Tenochtitlan and founded Mexico-Tlatelolco on the northern portion of the island. Tenochtitlan was closely tied with its sister city, which was largely dependent on the market of Tlatelolco, the most important site of commerce in the area.

Tenayuca is a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological site in the Valley of Mexico. In the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology, Tenayuca was a settlement on the former shoreline of the western arm of Lake Texcoco. It was located approximately 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to the northwest of Tenochtitlan.

In Mesoamerican culture, Tonatiuh is an Aztec sun deity of the daytime sky who rules the cardinal direction of east. According to Aztec Mythology, Tonatiuh was known as "The Fifth Sun" and was given a calendar name of naui olin, which means "4 Movement". Represented as a fierce and warlike god, he is first seen in Early Postclassic art of the Pre-Columbian civilization known as the Toltec. Tonatiuh's symbolic association with the eagle alludes to the Aztec belief of his journey as the present sun, travelling across the sky each day, where he descended in the west and ascended in the east. It was thought that his journey was sustained by the daily sacrifice of humans. His Nahuatl name can also be translated to "He Who Goes Forth Shining" or "He Who Makes The Day." Tonatiuh was thought to be the central deity on the Aztec calendar stone but is no longer identified as such. In Toltec culture, Tonatiuh is often associated with Quetzalcoatl in his manifestation as the morning star aspect of the planet Venus.

A macuahuitl is a weapon, a wooden club with several embedded obsidian blades. The name is derived from the Nahuatl language and means "hand-wood". Its sides are embedded with prismatic blades traditionally made from obsidian. Obsidian is capable of producing an edge sharper than high quality steel razor blades. The macuahuitl was a standard close combat weapon.

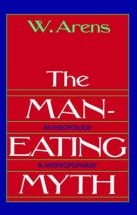

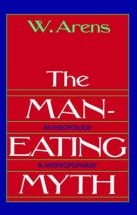

The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy is an influential anthropological study of socially sanctioned "cultural" cannibalism across the world, which casts a critical perspective on the existence of such practices. It was authored by the American anthropologist William Arens of Stony Brook University, New York, and first published by Oxford University Press in 1979.

Moctezuma's table refers to both the place and the manner in which the Aztec emperor (Tlatoani) ate his food. Important chronologists were witnesses to this daily ritual. One of these, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, extrapolated in his book, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain, how the Mexicas specific protocols and etiquette were passed down from one generation to the next. The abundance of typical meals that were found in this daily banquet are largely reflected in today's Mexican cuisine. Moctezuma's table represents more than just Aztec cuisine and the perfection of great eating because it also demonstrates the prerogative that was required to create them. Trade routes and agreements with civilizations bordering Aztec territory were essential in order to have the most delicious and fresh ingredients.

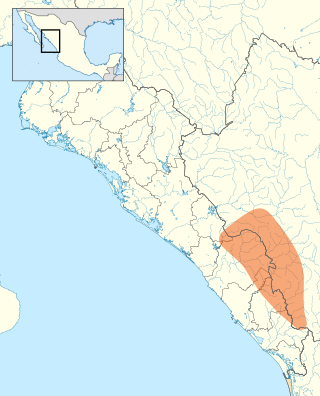

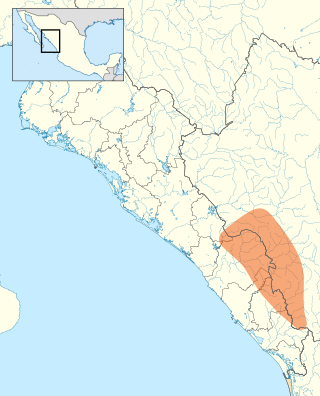

The Xixime were an indigenous people who inhabited a portion of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains in the present day states of Durango and Sinaloa, Mexico. The Xixime are noted for their reported practice of cannibalism and resistance to Spanish colonization in the form of the Xixime Rebellion of 1610.