Panama is a country located in Central America, bordering both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, between Colombia and Costa Rica. Panama is located on the narrow and low Isthmus of Panama.

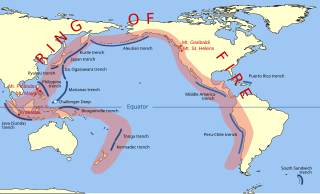

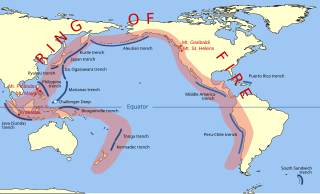

The Ring of Fire is a tectonic belt of volcanoes and earthquakes.

The Cocos Plate is a young oceanic tectonic plate beneath the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of Central America, named for Cocos Island, which rides upon it. The Cocos Plate was created approximately 23 million years ago when the Farallon Plate broke into two pieces, which also created the Nazca Plate. The Cocos Plate also broke into two pieces, creating the small Rivera Plate. The Cocos Plate is bounded by several different plates. To the northeast it is bounded by the North American Plate and the Caribbean Plate. To the west it is bounded by the Pacific Plate and to the south by the Nazca Plate.

Pacaya is an active complex volcano in Guatemala, which first erupted approximately 23,000 years ago and has erupted at least 23 times since the Spanish conquest of Guatemala. It rises to an elevation of 2,552 metres (8,373 ft). After being dormant for over 70 years, it began erupting vigorously in 1961 and has been erupting frequently since then. Much of its activity is Strombolian, but occasional Plinian eruptions also occur, sometimes showering the area of the nearby Departments with ash.

The Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, also known as the Transvolcanic Belt and locally as the Sierra Nevada, is an active volcanic belt that covers central-southern Mexico. Several of its highest peaks have snow all year long, and during clear weather, they are visible to a large percentage of those who live on the many high plateaus from which these volcanoes rise.

The Sunda Arc is a volcanic arc that produced the volcanoes that form the topographic spine of the islands of Sumatra, Nusa Tenggara, Java, the Sunda Strait, and the Lesser Sunda Islands. The Sunda Arc begins at Sumatra and ends at Flores, and is adjacent to the Banda Arc. The Sunda Arc is formed via the subduction of the Indo-Australian Plate beneath the Sunda and Burma plates at a velocity of 63–70 mm/year.

The Caribbean Plate is a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off the northern coast of South America.

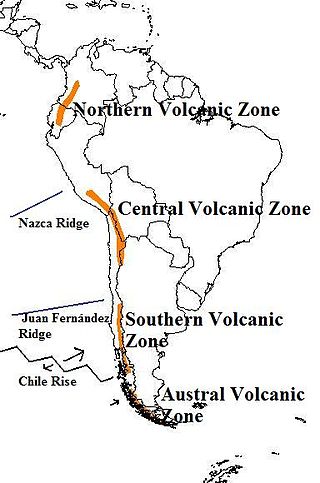

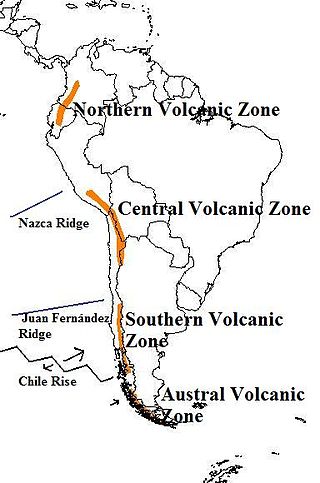

Cerro Azul, sometimes referred to as Quizapu, is an active stratovolcano in the Maule Region of central Chile, immediately south of Descabezado Grande. Part of the South Volcanic Zone of the Andes, its summit is 3,788 meters (12,428 ft) above sea level, and is capped by a summit crater that is 500 meters (1,600 ft) wide and opens to the north. Beneath the summit, the volcano features numerous scoria cones and flank vents.

The Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province (NCVP), formerly known as the Stikine Volcanic Belt, is a geologic province defined by the occurrence of Miocene to Holocene volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest of North America. This belt of volcanoes extends roughly north-northwest from northwestern British Columbia and the Alaska Panhandle through Yukon to the Southeast Fairbanks Census Area of far eastern Alaska, in a corridor hundreds of kilometres wide. It is the most recently defined volcanic province in the Western Cordillera. It has formed due to extensional cracking of the North American continent—similar to other on-land extensional volcanic zones, including the Basin and Range Province and the East African Rift. Although taking its name from the Western Cordillera, this term is a geologic grouping rather than a geographic one. The southmost part of the NCVP has more, and larger, volcanoes than does the rest of the NCVP; further north it is less clearly delineated, describing a large arch that sways westward through central Yukon.

El Valle is a stratovolcano in central Panama and is the easternmost volcano along the Central American Volcanic Arc which has been formed by the subduction of the Nazca Plate below Central America. Some time prior to 200,000 years ago, the volcano underwent a huge eruption event that caused the top of the volcano to collapse into the empty magma chamber below forming a large caldera. Several lava domes have developed inside the caldera since the collapse—forming Cerro Pajita, Cerro Gaital and Cerro Caracoral peaks. Prior to research in the early 1990s, it was thought that no active volcanism existed within Panama. But radioactive dates from El Valle show that the volcano last erupted as recently as 200,000 years ago.

Volcanic activity is a major part of the geology of Canada and is characterized by many types of volcanic landform, including lava flows, volcanic plateaus, lava domes, cinder cones, stratovolcanoes, shield volcanoes, submarine volcanoes, calderas, diatremes, and maars, along with less common volcanic forms such as tuyas and subglacial mounds.

The geology of the Pacific Northwest includes the composition, structure, physical properties and the processes that shape the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The region is part of the Ring of Fire: the subduction of the Pacific and Farallon Plates under the North American Plate is responsible for many of the area's scenic features as well as some of its hazards, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, and landslides.

The Andean Volcanic Belt is a major volcanic belt along the Andean cordillera in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It is formed as a result of subduction of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South American Plate. The belt is subdivided into four main volcanic zones which are separated by volcanic gaps. The volcanoes of the belt are diverse in terms of activity style, products, and morphology. While some differences can be explained by which volcanic zone a volcano belongs to, there are significant differences within volcanic zones and even between neighboring volcanoes. Despite being a type location for calc-alkalic and subduction volcanism, the Andean Volcanic Belt has a broad range of volcano-tectonic settings, as it has rift systems and extensional zones, transpressional faults, subduction of mid-ocean ridges and seamount chains as well as a large range of crustal thicknesses and magma ascent paths and different amounts of crustal assimilations.

The Izu–Bonin–Mariana (IBM) arc system is a tectonic plate convergent boundary in Micronesia. The IBM arc system extends over 2800 km south from Tokyo, Japan, to beyond Guam, and includes the Izu Islands, the Bonin Islands, and the Mariana Islands; much more of the IBM arc system is submerged below sealevel. The IBM arc system lies along the eastern margin of the Philippine Sea Plate in the Western Pacific Ocean. It is the site of the deepest gash in Earth's solid surface, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench.

The Panama Plate is a small tectonic plate (microplate) that exists between two actively spreading ridges and moves relatively independently of its surrounding plates. The Panama Plate is located between the Cocos Plate and the Nazca Plate to the south and the Caribbean Plate to the north. Most of its borders are convergent boundaries, including a subduction zone to the west. It consists, for the most part, of the countries of Costa Rica and Panama.

Aguas Calientes is a major Miocene caldera in Salta Province, Argentina. It is in the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, a zone of volcanism covering southern Peru, Bolivia, northwest Argentina and northern Chile. This zone contains stratovolcanoes and calderas.

Jotabeche is a Miocene-Pliocene caldera in the Atacama Region of Chile. It is part of the volcanic Andes, more specifically of the extreme southern end of the Central Volcanic Zone (CVZ). This sector of the Andean Volcanic Belt contains about 44 volcanic centres and numerous more minor volcanic systems, as well as some caldera and ignimbrite systems. Jotabeche is located in a now inactive segment of the CVZ, the Maricunga Belt.

La Negra Formation is a geologic formation of Jurassic age, composed chiefly of volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks, located in the Coast Range of northern Chile. The formation originated in marine and continental (terrestrial) conditions, and bears evidence of submarine volcanism as well as large explosive eruptions. The volcanism of La Negra Formation is thought to have lasted for about five million years.

The geology of Nicaragua includes Paleozoic crystalline basement rocks, Mesozoic intrusive igneous rocks and sedimentary rocks spanning the Cretaceous to the Pleistocene. Volcanoes erupted in the Paleogene and within the last 2.5 million years of the Quaternary, due to the subduction of the Cocos Plate, which drives melting and magma creation. Many of these volcanoes are in the Nicaraguan Depression paralleled by the northwest-trending Middle America Trench which marks the Caribbean-Cocos plate boundary. Almost all the rocks in Nicaragua originated as dominantly felsic continental crust, unlike other areas in the region which include stranded sections of mafic oceanic crust. Structural geologists have grouped all the rock units as the Chortis Block.

The geology of Costa Rica is part of the Panama Microplate, which is slowly moving north relative to the stable Caribbean Plate.