The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execution of Charles I. The republic's existence was declared through "An Act declaring England to be a Commonwealth", adopted by the Rump Parliament on 19 May 1649. Power in the early Commonwealth was vested primarily in the Parliament and a Council of State. During the period, fighting continued, particularly in Ireland and Scotland, between the parliamentary forces and those opposed to them, in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish war of 1650–1652.

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In September 1640, King Charles I issued writs summoning a parliament to convene on 3 November 1640. He intended it to pass financial bills, a step made necessary by the costs of the Bishops' Wars against Scotland. The Long Parliament received its name from the fact that, by Act of Parliament, it stipulated it could be dissolved only with agreement of the members; and those members did not agree to its dissolution until 16 March 1660, after the English Civil War and near the close of the Interregnum.

Richard Cromwell was an English statesman, the second and final Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and the son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland, with their associated territories were joined together in the Commonwealth of England, governed by a Lord Protector. It began when Barebone's Parliament was dissolved, and the Instrument of Government appointed Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. Cromwell died in September 1658 and was succeeded by his son Richard Cromwell.

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle KG PC JP was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was crucial to the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, who rewarded him with the title Duke of Albemarle and other senior positions.

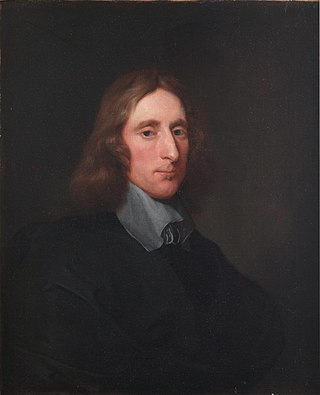

John Lambert was an English Parliamentarian general and politician. Widely regarded as one of the most talented soldiers of the period, he fought throughout the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and was largely responsible for victory in the 1650 to 1651 Scottish campaign.

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

Edmund Ludlow was an English parliamentarian, best known for his involvement in the execution of Charles I, and for his Memoirs, which were published posthumously in a rewritten form and which have become a major source for historians of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Ludlow was elected a Member of the Long Parliament and served in the Parliamentary armies during the English Civil Wars. After the establishment of the Commonwealth in 1649 he was made second-in-command of Parliament's forces in Ireland, before breaking with Oliver Cromwell over the establishment of the Protectorate. After the Restoration Ludlow went into exile in Switzerland, where he spent much of the rest of his life. Ludlow himself spelt his name Ludlowe.

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms, sometimes known as the British Civil Wars, were a series of intertwined conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bishops' Wars, the First and Second English Civil Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish War of 1650–1652. They resulted in victory for the Parliamentarian army, the execution of Charles I, the abolition of monarchy, and founding of the Commonwealth of England, a unitary state which controlled the British Isles until the Stuart Restoration in 1660.

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland with the New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in August 1649.

John Desborough (1608–1680) was an English soldier and politician who supported the parliamentary cause during the English Civil War.

Colonel Daniel Axtell, c. 1622 to 19 October 1660, was a grocer and religious radical from Hertfordshire who served with the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. He was in charge of security during the Trial of Charles I at Westminster Hall in January 1649, and as a result was excluded from the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion after the 1660 Stuart Restoration. He was hanged, drawn and quartered for treason on 19 October 1660.

Colonel Sir Richard Ingoldsby was an English officer in the New Model Army during the English Civil War and a politician who sat in the House of Commons variously between 1647 and 1685. As a Commissioner (Judge) at the trial of King Charles I, he signed the king's death warrant but was one of the few regicides to be pardoned.

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660, which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various forms of republican government.

Events from the year 1659 in England.

Francis Lascelles (1612-1667), also spelt Lassels, was an English politician, soldier and businessman who fought for Parliament in the 1639-1652 Wars of the Three Kingdoms and was a Member of Parliament between 1645 and 1660.

James Berry, died 9 May 1691, was a Clerk from the West Midlands who served with the Parliamentarian army in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Characterised by a contemporary and friend as "one of Cromwell's favourites", during the 1655 to 1657 Rule of the Major-Generals, he was administrator for Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Shropshire and Wales.

The Restoration of the monarchy began in 1660. The Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland (1649–1660) resulted from the Wars of the Three Kingdoms but collapsed in 1659. Politicians such as General Monck tried to ensure a peaceful transition of government from the "Commonwealth" republic back to monarchy. From 1 May 1660 the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under King Charles II. The term Restoration may apply both to the actual event by which the monarchy was restored, and to the period immediately before and after the event.

Scotland under the Commonwealth is the history of the Kingdom of Scotland between the declaration that the kingdom was part of the Commonwealth of England in February 1652, and the Restoration of the monarchy with Scotland regaining its position as an independent kingdom, in June 1660.

Ireland during the Interregnum (1649–1660) covers the period from the execution of Charles I until the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660.