Chinese Indonesians, colloquially Cindo, Chindo or simply Orang Tionghoa or Tionghoa are Indonesians whose ancestors arrived from China at some stage in the last eight centuries. Chinese Indonesians are the fourth largest community of Overseas Chinese in the world after Thailand, Malaysia, and the United States.

British Chinese, also known as Chinese British or Chinese Britons, are people of Chinese – particularly Han Chinese – ancestry who reside in the United Kingdom, constituting the second-largest group of Overseas Chinese in Western Europe after France.

Chinese Singaporeans are Singaporeans of Han Chinese ancestry. Chinese Singaporeans constitute 75.9% of the Singaporean citizen population according to the official census, making them the largest ethnic group in Singapore.

Chinese Australians are Australians of Chinese origin. Chinese Australians are one of the largest groups within the global Chinese diaspora, and are the largest Asian Australian community. Per capita, Australia has more people of Chinese ancestry than any country outside Asia. As a whole, Australian residents identifying themselves as having Chinese ancestry made up 5.5% of Australia's population at the 2021 census.

The Cantonese people or Yue people, are a Han Chinese subgroup originating from or residing in the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, in southern mainland China. In a strict sense, "Cantonese" refers only to people with roots from Guangzhou and its satellite cities and towns, rather than generally referring to the people of the Liangguang region.

Cài is a Chinese-language surname that derives from the name of the ancient Cai state. In 2019 it was the 38th most common surname in China, but the 9th most common in Taiwan, where it is usually romanized as "Tsai", "Tsay", or "Chai" and the 8th most common in Singapore, where it is usually romanized as "Chua", which is based on its Teochew and Hokkien pronunciation. Koreans use Chinese-derived family names and in Korean, Cai is 채 in Hangul, "Chae" in Revised Romanization, It is also a common name in Hong Kong where it is romanized as "Choy", "Choi" or "Tsoi". In Macau, it is spelled as "Choi". In Malaysia, it is romanized as "Choi" from the Cantonese pronunciation, and "Chua" or "Chuah" from the Hokkien or Teochew pronunciation. It is romanized in the Philippines as "Chua" or "Chuah", and in Thailand as "Chuo" (ฉั่ว). Moreover, it is also romanized in Cambodia as either "Chhay" or "Chhor" among people of full Chinese descent living in Cambodia and as “Tjhai”, "Tjoa" or "Chua" in Indonesia.

Chinese Jamaicans are Jamaicans of Chinese ancestry, which include descendants of migrants from China to Jamaica. Early migrants came in the 19th century; there was another moment of migration in the 1980s and 1990s. Many of the descendants of early migrants have moved abroad, primarily to Canada and the United States. Most Chinese Jamaicans are Hakka and many can trace their origin to the indentured Chinese laborers who came to Jamaica in the mid-19th to early 20th centuries.

Indonesian Americans are migrants from the multiethnic country of Indonesia to the United States, and their U.S.-born descendants. In both the 2000 and 2010 United States census, they were the 15th largest group of Asian Americans recorded in the United States as well as one of the fastest growing.

Waves of Chinese emigration have happened throughout history. They include the emigration to Southeast Asia beginning from the 10th century during the Tang dynasty, to the Americas during the 19th century, particularly during the California gold rush in the mid-1800s; general emigration initially around the early to mid 20th century which was mainly caused by corruption, starvation, and war due to the Warlord Era, the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War; and finally elective emigration to various countries. Most emigrants were peasants and manual labourers, although there were also educated individuals who brought their various expertises to their new destinations. As of 2023, illegal Chinese immigration to New York City has accelerated, and its Flushing (法拉盛), Queens neighborhood has become the present-day global epicenter receiving Chinese immigration as well as the international control center directing such migration.

Tan is a common Chinese surname 譚, and is considered the 56th most common.

Lin is the Mandarin romanization of the Chinese surname written 林. It is also used in Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia.

Indonesians in Hong Kong, numbering 102,100, form the second-largest ethnic minority group in the territory, behind Filipinos. Most Indonesians coming to Hong Kong today are those who arrive under limited-term contracts for employment as foreign domestic helpers. The Hong Kong Immigration Department allows the Indonesian consulate to force Indonesian domestic helpers to use employment agencies. Indonesian migrant workers in Hong Kong comprise 2.4% of all overseas Indonesian workers. Among the Indonesian population is a group of Chinese Indonesians, many of them finding refuge in Hong Kong after the civil persecution of them.

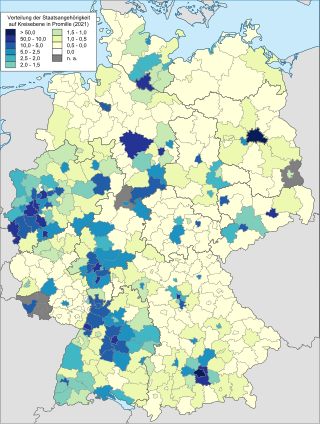

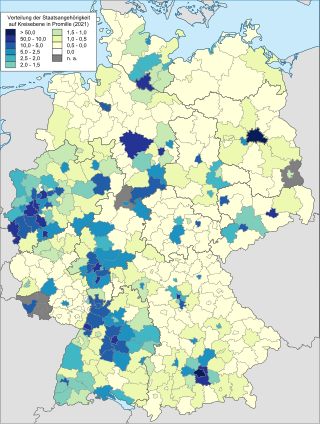

Chinese people in Germany form one of the smaller groups of overseas Chinese in Europe, consisting mainly of Chinese expatriates living in Germany and German citizens of Chinese descent. The German Chinese community is growing rapidly and, as of 2016, was estimated to be around 212,000 by the Federal Institute for Population Research. In comparison to that, the Taiwanese OCAC had estimated there were 110,000 people of Chinese descent living in Germany in 2008.

Chinese people in Denmark form one of the smaller and less-studied Chinese diaspora communities of Europe. Many chinese do voice work out of Denmark

Taishanese people, Sze Yup people, or Toisanese are a Han Chinese group coming from Sze Yup, which consisted of the four county-level cities of Taishan, Kaiping, Xinhui and Enping. Heshan has since been added to this historic region and the prefecture-level city of Jiangmen administers all five of these county-level cities, which are sometimes informally called Ng Yap. The ancestors of Taishanese people are said to have arrived from central China under a thousand years ago and migrated into Guangdong during the Tang Dynasty. Taishanese, as a dialect of Yue Chinese, has linguistically preserved many characteristics of Middle Chinese.

A Chinese restaurant is a restaurant that serves Chinese cuisine. Most of them are in the Cantonese style, due to the history of the Chinese diaspora, though other regional cuisines such as Sichuan cuisine and Hakka cuisine are also common. Many Chinese restaurants may adapt their cuisine to fit local taste preferences, as in British Chinese cuisine and American Chinese cuisine. Some Chinese restaurants may also serve other Asian cuisines in their menus, such as Japanese, Korean, Indonesian, or Thai cuisines, though their selection is often limited and minimal compared to Chinese dishes.

Hong Kong Americans, include Americans who are also Hong Kong residents who identify themselves as Hong Kongers, Americans of Hong Kong ancestry, and also Americans who have Hong Kong parents.

Hongkongers in the Netherlands are people in the Netherlands originated from Hong Kong or having at least once such parent.

Chung Hwa Hui was a conservative, largely pro-Dutch political organization and party in the Dutch East Indies, often criticised as a mouthpiece of the colonial Chinese establishment. The party campaigned for legal equality between the colony's ethnic Chinese subjects and Europeans, and advocated ethnic Chinese political participation in the Dutch colonial state. The CHH was led by scions of the 'Cabang Atas' gentry, including its founding president, H. H. Kan, and supported by ethnic Chinese conglomerates, such as the powerful Kian Gwan multinational.