Internal medicine, also known as general internal medicine in Commonwealth nations, is a medical specialty for medical doctors focused on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of internal diseases in adults. Medical practitioners of internal medicine are referred to as internists, or physicians in Commonwealth nations. Internists possess specialized skills in managing patients with undifferentiated or multi-system disease processes. They provide care to both hospitalized (inpatient) and ambulatory (outpatient) patients and often contribute significantly to teaching and research. Internists are qualified physicians who have undergone postgraduate training in internal medicine, and should not be confused with "interns", a term commonly used for a medical doctor who has obtained a medical degree but does not yet have a license to practice medicine unsupervised.

In a physical examination, medical examination, clinical examination, or medical checkup, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a medical condition. It generally consists of a series of questions about the patient's medical history followed by an examination based on the reported symptoms. Together, the medical history and the physical examination help to determine a diagnosis and devise the treatment plan. These data then become part of the medical record.

A primary care physician (PCP) is a physician who provides both the first contact for a person with an undiagnosed health concern as well as continuing care of varied medical conditions, not limited by cause, organ system, or diagnosis. The term is primarily used in the United States. In the past, the equivalent term was 'general practitioner' in the US; however in the United Kingdom and other countries the term general practitioner is still used. With the advent of nurses as PCPs, the term PCP has also been expanded to denote primary care providers.

Defensive medicine, also called defensive medical decision making, refers to the practice of recommending a diagnostic test or medical treatment that is not necessarily the best option for the patient, but mainly serves to protect the physician against the patient as potential plaintiff. Defensive medicine is a reaction to the rising costs of malpractice insurance premiums and patients’ biases on suing for missed or delayed diagnosis or treatment but not for being overdiagnosed.

Fee-for-service (FFS) is a payment model where services are unbundled and paid for separately.

David Lawrence Sackett was an American-Canadian physician and a pioneer in evidence-based medicine. He is known as one of the fathers of Evidence-Based Medicine. He founded the first department of clinical epidemiology in Canada at McMaster University, and the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. He is well known for his textbooks Clinical Epidemiology and Evidence-Based Medicine.

A caregiver, carer or support worker is a paid or unpaid person who helps an individual with activities of daily living. Caregivers who are members of a care recipient's family or social network, and who may have no specific professional training, are often described as informal caregivers. Caregivers most commonly assist with impairments related to old age, disability, a disease, or a mental disorder.

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, self-appointed physician-evaluation organization that certifies physicians practicing internal medicine and its subspecialties. The American Board of Internal Medicine is not a membership society, educational institution, or licensing body.

The National Physicians Alliance (NPA) was a 501(c)(3) national, multi-specialty medical organization founded in 2005. The organization's mission statement was: "The National Physicians Alliance creates research and education programs that promote health and foster active engagement of physicians with their communities to achieve high quality, affordable health care for all. The NPA offers a professional home to physicians across medical specialties who share a commitment to professional integrity and health justice." In 2019, they merged with Doctors for America.

John E. "Jack" Wennberg was the pioneer and leading researcher of unwarranted variation in the healthcare industry. In four decades of work, Wennberg has documented the geographic variation in the healthcare that patients receive in the United States. In 1988, he founded the Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences at Dartmouth Medical School to address that unwarranted variation in healthcare.

Michael Alan Grodin is Professor of Health Law, Bioethics, and Human Rights at the Boston University School of Public Health, where he has received the distinguished Faculty Career Award for Research and Scholarship, and 20 teaching awards, including the "Norman A. Scotch Award for Excellence in Teaching." He is also Professor of Family Medicine and Psychiatry at the Boston University School of Medicine. In addition, Dr. Grodin is the Director of the Project on Medicine and the Holocaust at the Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies, and a member of the faculty of the Division of Religious and Theological Studies. He has been on the faculty at Boston University for 35 years. He completed his B.S. degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his M.D. degree from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and his postdoctoral and fellowship training at UCLA and Harvard University.

David M. Eddy is an American physician, mathematician, and healthcare analyst who has done seminal work in mathematical modeling of diseases, clinical practice guidelines, and evidence-based medicine. Four highlights of his career have been summarized by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences: "more than 25 years ago, Eddy wrote the seminal paper on the role of guidelines in medical decision-making, the first Markov model applied to clinical problems, and the original criteria for coverage decisions; he was the first to use and publish the term 'evidence-based'."

Unnecessary health care is health care provided with a higher volume or cost than is appropriate. In the United States, where health care costs are the highest as a percentage of GDP, overuse was the predominant factor in its expense, accounting for about a third of its health care spending in 2012.

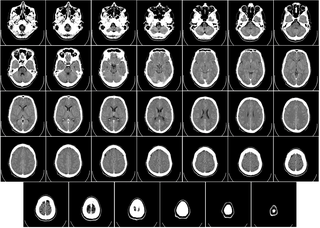

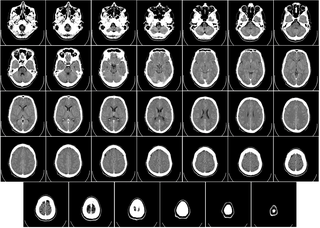

Computed tomography of the head uses a series of X-rays in a CT scan of the head taken from many different directions; the resulting data is transformed into a series of cross sections of the brain using a computer program. CT images of the head are used to investigate and diagnose brain injuries and other neurological conditions, as well as other conditions involving the skull or sinuses; it used to guide some brain surgery procedures as well. CT scans expose the person getting them to ionizing radiation which has a risk of eventually causing cancer; some people have allergic reactions to contrast agents that are used in some CT procedures.

Overscreening, also called unnecessary screening, is the performance of medical screening without a medical indication to do so. Screening is a medical test in a healthy person who is showing no symptoms of a disease and is intended to detect a disease so that a person may prepare to respond to it. Screening is indicated in people who have some threshold risk for getting a disease, but is not indicated in people who are unlikely to develop a disease. Overscreening is a type of unnecessary health care.

Preoperative care refers to health care provided before a surgical operation. Preoperative care aims to do whatever is right to increase the success of the surgery.

Penny Wise Budoff was an American physician. She was a family practitioner, and a clinical associate professor of family medicine at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. She is known for her research, which established that menstrual cramping is a physical phenomenon rather than a psychological one. She wrote two books on women's health.

Wendy Levinson MD is a Canadian physician and academic. She is the Chair of Choosing Wisely Canada, "a campaign to help physicians and patients engage in conversations about unnecessary tests, treatments and procedures". She is also Professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Conflict of interest in the health care industry occurs when the primary goal of protecting and increasing the health of patients comes into conflict with any other secondary goal, especially personal gain to healthcare professionals, and increasing revenue to a healthcare organization from selling health care products and services. The public and private sectors of the medical-industrial complex have various conflicts of interest which are specific to these entities.

Choosing Wisely Canada (CWC) is a Canadian-based health education campaign launched on April 2, 2014 under the leadership of Wendy Levinson, in partnership with the Canadian Medical Association, and based at Unity Health Toronto and the University of Toronto. The campaign aims to help clinicians and patients engage in conversations about unnecessary tests, treatments and procedures, and to assist physicians and patients in making informed and effective choices to ensure high quality care.