The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club or simply the Jacobins, was the most influential political club during the French Revolution of 1789. The period of its political ascendancy includes the Reign of Terror, during which well over 10,000 people were put on trial and executed in France, many for political crimes.

The Girondins, or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initially were part of the Jacobin movement. They campaigned for the end of the monarchy, but then resisted the spiraling momentum of the Revolution, which caused a conflict with the more radical Montagnards. They dominated the movement until their fall in the insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, which resulted in the domination of the Montagnards and the purge and eventual mass execution of the Girondins. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

Charles Victoire Emmanuel Leclerc was a French Army general who served under Napoleon Bonaparte during the French Revolution. He was husband to Pauline Bonaparte, sister to Napoleon. In 1801, he was sent to Saint-Domingue (Haiti), where an expeditionary force under his command captured and deported the Haitian leader Toussaint L'Ouverture, as part of an unsuccessful attempt to reassert imperial control over the Saint-Domingue government. Leclerc died of yellow fever during the failed expedition.

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont, known as Charlotte Corday, was a figure of the French Revolution. In 1793, she was executed by guillotine for the assassination of Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who was in part responsible for the more radical course the Revolution had taken through his role as a politician and journalist. Marat had played a substantial role in the political purge of the Girondins, with whom Corday sympathized. His murder was depicted in the painting The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David, which shows Marat's dead body after Corday had stabbed him in his medicinal bath. In 1847, writer Alphonse de Lamartine gave Corday the posthumous nickname l'ange de l'assassinat.

The sans-culottes were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the Ancien Régime. The word sans-culotte, which is opposed to "aristocrat", seems to have been used for the first time on 28 February 1791 by Jean-Bernard Gauthier de Murnan in a derogatory sense, speaking about a "sans-culottes army". The word came into vogue during the demonstration of 20 June 1792.

Olympe de Gouges was a French playwright and political activist whose writings on women's rights and abolitionism reached a large audience in various countries. She began her career as a playwright in the early 1780s. As political tension rose in France, Olympe de Gouges became increasingly politically engaged. She became an outspoken advocate against the slave trade in the French colonies in 1788. At the same time, she began writing political pamphlets. In her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (1791), she challenged the practice of male authority and the notion of male-female inequality. She was executed by guillotine during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794) for attacking the regime of the Revolutionary government and for her association with the Girondists.

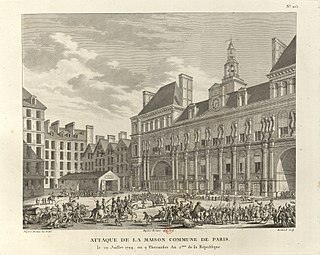

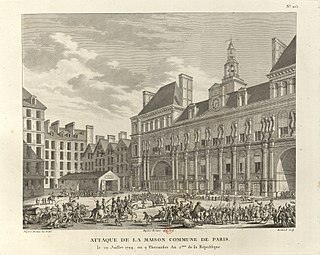

The Paris Commune during the French Revolution was the government of Paris from 1789 until 1795. Established in the Hôtel de Ville just after the storming of the Bastille, it consisted of 144 delegates elected by the 60 divisions of the city. Before its formal establishment, there had been much popular discontent on the streets of Paris over who represented the true Commune, and who had the right to rule the Parisian people. The first mayor was Jean Sylvain Bailly, a relatively moderate Feuillant who supported constitutional monarchy. He was succeeded in November 1791 by Pétion de Villeneuve after Bailly's unpopular use of the National Guard to disperse a riotous assembly in the Champ de Mars.

The term "fédérés" most commonly refers to the troops who volunteered for the French National Guard in the summer of 1792 during the French Revolution. The fédérés of 1792 effected a transformation of the Guard from a constitutional monarchist force into a republican revolutionary force.

Jacques Roux was a radical Roman Catholic priest who took an active role in politics during the French Revolution. He skillfully expounded the ideals of popular democracy and classless society to crowds of Parisian sans-culottes, working class wage earners and shopkeepers, radicalizing them into a revolutionary force. He became a leader of a popular far-left.

Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital is a teaching hospital in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. Part of the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris and a teaching hospital of Sorbonne University.

The Enragés commonly known as the Ultra-radicals were a small number of firebrands known for defending the lower class and expressing the demands of the extreme radical sans-culottes during the French Revolution. They played an active role in the 31 May – 2 June 1793 Paris uprisings that forced the expulsion of the Girondins from the National Convention, allowing the Montagnards to assume full control. The Enragés became associated with this term for their angry rhetoric appealing to the National Convention to take more measures that would benefit the poor. Jacques Roux, Jean-François Varlet, Jean Théophile Victor Leclerc and Claire Lacombe, the primary leaders of the Enragés, were strident critics of the National Convention for failing to carry out the promises of the French Revolution.

The Revolutionary Tribunal was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. It eventually became one of the most powerful engines of the Reign of Terror.

Catherine Théot was a French visionary. Catherine believed she was destined to work for God. She gained notoriety when she was accused of being involved in a plot to overthrow the Republic, and the downfall of Maximilien Robespierre was attributed in part to her prophecies.

Anne-Josèphe Théroigne de Méricourt was a Belgian singer, orator and organizer in the French Revolution. She was born at Marcourt, in Prince-Bishopric of Liège, a small town in the modern Belgian province of Luxembourg. She was active in the French Revolution and worked within the Austrian Low Countries to also foster revolution. She was held in an Austrian prison from 1791 to 1792 for being an agent provocateur in Belgium. She was a cofounder of a Parisian revolutionary club and had warrants for her arrest issued in France for her alleged participation in the October Days uprising. She is known both for her portrayal in the French Revolutionary press and for her subsequent mental breakdown and institutionalization.

Jean Théophile Victor Leclerc, a.k.a. Jean-Theophilus Leclerc and Theophilus Leclerc d'Oze, was a radical French revolutionary, publicist, and soldier. After Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated, Leclerc assumed his mantle.

Pauline Léon was an influential woman during the French Revolution. She played an important role in the Revolution, driven by her strong feminist and anti-royalist beliefs. Along with her friend Claire Lacombe, founded the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, and she also served as a prominent leader of the Femmes Sans-Culottes.

In pre-revolutionary France, women had little part in affairs outside the house. Before the revolution and the advent of feminism in France, women's roles in society consisted of providing heirs for their husbands and tending to household duties. Even in the upper classes, women were dismissed as simpletons, unable to understand or give a meaningful contribution to the philosophical or political conversations of the day. However, with the emergence of ideas such as liberté, égalité, and fraternité, the women of France joined their voices to the chaos of the early revolution. This was the beginning of feminism in France. With demonstrations such as the Women's March on Versailles, and the Demonstration of 20 June 1792, women displayed their commitment to the Revolution. Both the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen and the creation of the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women further conveyed their message of women's rights as a necessity to the new order of the revolution.

The Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women was a female-led revolutionary organization during the French Revolution. The Society officially began on May 10, 1793 and disbanded on September 16 of the same year. During its existence, the Society managed to draw significant interest within the national political scene and advocation for gender equality in revolutionary politics.

Historians since the late 20th century have debated how women shared in the French Revolution and what impact it had on French women. Women had no political rights in pre-Revolutionary France; they were considered "passive" citizens, forced to rely on men to determine what was best for them. That changed dramatically in theory as there seemingly were great advances in feminism. Feminism emerged in Paris as part of a broad because of demand for social and political reform. These women demanded equality to men and then moved on to a demand for the end of male domination. Their chief vehicle for agitation were pamphlets and women's clubs, especially the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women. However, the Jacobin element in power abolished all the women's clubs in October 1793 and arrested their leaders. The movement was crushed. Devance explains the decision in terms of the emphasis on masculinity in wartime, Marie Antoinette's bad reputation for feminine interference in state affairs, and traditional male supremacy. A decade later the Napoleonic Code confirmed and perpetuated women's second-class status.

Anne Félicité Colombe, was a French printer and publisher, and a political activist during the French revolution. She published the radical journals L'Ami du Peuple and l'Orateur du Peuple.