Safety is the state of being "safe", the condition of being protected from harm or other non-desirable outcomes. Safety can also refer to the control of recognized hazards in order to achieve an acceptable level of risk.

Caveat emptor is Latin for "Let the buyer beware". Generally, caveat emptor is the contract law principle that controls the sale of real property after the date of closing, but may also apply to sales of other goods. The phrase caveat emptor and its use as a disclaimer of warranties arise from the fact that buyers typically have less information than the seller about the good or service they are purchasing. This quality of the situation is known as 'information asymmetry'. Defects in the good or service may be hidden from the buyer, and only known to the seller.

In criminal law, criminal negligence is a surrogate mens rea required to constitute a conventional as opposed to strict liability offense. It is not, strictly speaking, a mens rea because it refers to an objective standard of behaviour expected of the defendant and does not refer to their mental state.

In the United States, the calculus of negligence, also known as the Hand rule, Hand formula, or BPL formula, is a term coined by Judge Learned Hand and describes a process for determining whether a legal duty of care has been breached. The original description of the calculus was in United States v. Carroll Towing Co., in which an improperly secured barge had drifted away from a pier and caused damage to several other boats.

In tort law, a duty of care is a legal obligation which is imposed on an individual requiring adherence to a standard of reasonable care while performing any acts that could foreseeably harm others. It is the first element that must be established to proceed with an action in negligence. The claimant must be able to show a duty of care imposed by law which the defendant has breached. In turn, breaching a duty may subject an individual to liability. The duty of care may be imposed by operation of law between individuals who have no current direct relationship but eventually become related in some manner, as defined by common law.

English tort law concerns the compensation for harm to people's rights to health and safety, a clean environment, property, their economic interests, or their reputations. A "tort" is a wrong in civil, rather than criminal law, that usually requires a payment of money to make up for damage that is caused. Alongside contracts and unjust enrichment, tort law is usually seen as forming one of the three main pillars of the law of obligations.

In tort law, the standard of care is the only degree of prudence and caution required of an individual who is under a duty of care.

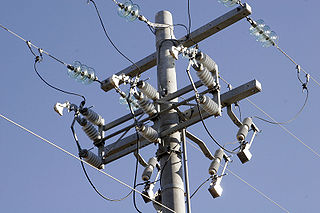

Forensic electrical engineering is a branch of forensic engineering, and is concerned with investigating electrical failures and accidents in a legal context. Many forensic electrical engineering investigations apply to fires suspected to be caused by electrical failures. Forensic electrical engineers are most commonly retained by insurance companies or attorneys representing insurance companies, or by manufacturers or contractors defending themselves against subrogation by insurance companies. Other areas of investigation include accident investigation involving electrocution, and intellectual property disputes such as patent actions. Additionally, since electrical fires are most often cited as the cause for "suspect" fires an electrical engineer is often employed to evaluate the electrical equipment and systems to determine whether the cause of the fire was electrical in nature.

Trimarco v. Klein Ct. of App. of N.Y., 56 N.Y.2d 98, 436 N.E.2d 502 (1982) is a 1982 decision by the New York Court of Appeals dealing with the use of custom in determining whether a person acted reasonably given the situation. It is commonly studied in introductory U.S. tort law classes.

Irish law on product liability was for most of its history based solely on negligence. With the Liability for Defective Products Act, 1991 it has now also the benefit of a statutory, strict liability regime.

The Consumer Protection Act 1987 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that made important changes to the consumer law of the United Kingdom. Part 1 implemented European Community (EC) Directive 85/374/EEC, the product liability directive, by introducing a regime of strict liability for damage arising from defective products. Part 2 created government powers to regulate the safety of consumer products through Statutory Instruments. Part 3 defined a criminal offence of giving a misleading price indication.

The Liability for Defective Products Act 1991 is an Act of the Oireachtas that augmented Irish law on product liability formerly based solely on negligence. It introduced a strict liability regime for defective products, implementing Council of the European Union Directive 85/374/EEC.

Grant v Australian Knitting Mills, is a landmark case in consumer and negligence law from 1935, holding that where a manufacturer knows that a consumer may be injured if the manufacturer does not take reasonable care, the manufacturer owes a duty to the consumer to take that reasonable care. It continues to be cited as an authority in legal cases, and used as an example for students studying law.

The Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) of 2008 is a United States law signed on August 14, 2008 by President George W. Bush. The legislative bill was known as HR 4040, sponsored by Congressman Bobby Rush (D-Ill.). On December 19, 2007, the U.S. House approved the bill 407-0. On March 6, 2008, the U.S. Senate approved the bill 79-13. The law—public law 110-314—increases the budget of the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), imposes new testing and documentation requirements, and sets new acceptable levels of several substances. It imposes new requirements on manufacturers of apparel, shoes, personal care products, accessories and jewelry, home furnishings, bedding, toys, electronics and video games, books, school supplies, educational materials and science kits. The Act also increases fines and specifies jail time for some violations.

When a person makes a claim for personal injury damages that have resulted from the presence of a defective automobile or component of an automobile, that person asserts a product liability claim. That claim may be against the automobile's manufacturer, the manufacturer of a component part or system, or both, as well as potentially being raised against companies that distributed, sold or installed the part or system that is alleged to be defective.

Loop v. Litchfield 42 N. Y. 351 (1870) was a part of the historic line of cases holding that the privity requirement barred a products liability action unless the product in question was "inherently dangerous."

A product defect is any characteristic of a product which hinders its usability for the purpose for which it was designed and manufactured.

Increases in the use of autonomous car technologies is causing incremental shifts in the responsibility of driving, with the primary motivation of reducing the frequency of on the road accidents. Liability for incidents involving self-driving cars is a developing area of law and policy that will determine who is liable when a car causes physical damage to persons or property. As autonomous cars shift the responsibility of driving from humans to autonomous car technology, there is a need for existing liability laws to evolve in order to fairly identify the appropriate remedies for damage and injury. As higher levels of autonomy are commercially introduced, the insurance industry stands to see greater proportions of commercial and product liability lines, while personal automobile insurance shrinks.