Augustine of Canterbury was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founding figure of the Church of England.

Justus was the fourth Archbishop of Canterbury. He was sent from Italy to England by Pope Gregory the Great, on a mission to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism, probably arriving with the second group of missionaries despatched in 601. Justus became the first Bishop of Rochester in 604, and attended a church council in Paris in 614.

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group that inhabited much of what is now England in the Early Middle Ages, and spoke Old English. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. Although the details are not clear, their cultural identity developed out of the interaction of incoming groups of Germanic peoples, with the pre-existing Romano-British culture. Over time, most of the people of what is now southern and eastern England came to identify as Anglo-Saxon and speak Old English. Danish and Norman invasions later changed the situation significantly, but their language and political structures are the direct predecessors of the medieval Kingdom of England, and the Middle English language. Although the modern English language owes somewhat less than 26% of its words to Old English, this includes the vast majority of words used in everyday speech.

Edgar was King of England from 959 until his death. He became king of all England on his brother's death. He was the younger son of King Edmund I and his first wife Ælfgifu. A detailed account of Edgar's reign is not possible, because only a few events were recorded by chroniclers and monastic writers were more interested in recording the activities of the leaders of the church.

Æthelstan or Athelstan was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Modern historians regard him as the first King of England and one of the "greatest Anglo-Saxon kings". He never married and had no children; he was succeeded by his half-brother, Edmund I.

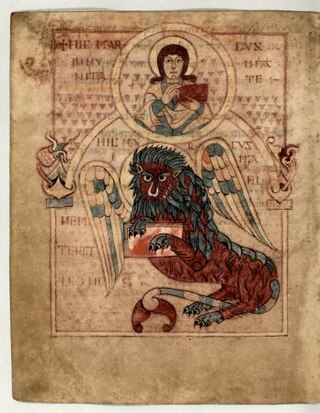

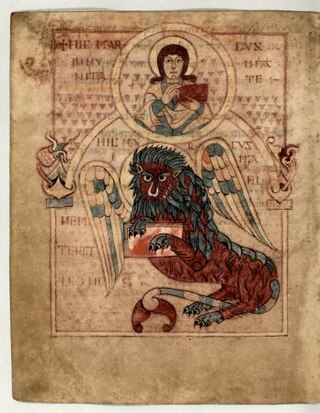

The Lindisfarne Gospels is an illuminated manuscript gospel book probably produced around the years 715–720 in the monastery at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland, which is now in the British Library in London. The manuscript is one of the finest works in the unique style of Hiberno-Saxon or Insular art, combining Mediterranean, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic elements.

The Book of Cerne is an early ninth-century Insular or Anglo-Saxon Latin personal prayer book with Old English components. It belongs to a group of four such early prayer books, the others being the Royal Prayerbook, the Harleian prayerbook, and the Book of Nunnaminster. It is now commonly believed to have been produced sometime between ca. 820 and 840 AD in the Southumbrian/Mercian region of England. The original book contains a collection of several different texts, including New Testament Gospel excerpts, a selection of prayers and hymns with a version of the Lorica of Laidcenn, an abbreviated or Breviate Psalter, and a text of the Harrowing of Hell liturgical drama, which were combined to provide a source used for private devotion and contemplation. Based on stylistic and palaeographical features, the Book of Cerne has been included within the Canterbury or Tiberius group of manuscripts that were manufactured in southern England in the 8th and 9th centuries AD associated with the Mercian hegemony in Anglo-Saxon England. This Anglo-Saxon manuscript is considered to be the most sophisticated and elaborate of this group. The Book of Cerne exhibits various Irish/Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Continental, and Mediterranean influences in its texts, ornamentation, and embellishment.

The Hereford Gospels is an 8th-century illuminated manuscript gospel book in insular script (minuscule), with large illuminated initials in the Insular style. This is a very late Anglo-Saxon gospel book, which shares a distinctive style with the Caligula Troper. An added text suggests this was in the diocese of Hereford in the 11th century.

British Library, Add MS 40618 is a late 8th century illuminated Irish Gospel Book with 10th century Anglo-Saxon additions. The manuscript contains a portion of the Gospel of Matthew, the majority of the Gospel of Mark and the entirety of the Gospels of Luke and John. There are three surviving Evangelist portraits, one original and two 10th century replacements, along with 10th century decorated initials. It is catalogued as number 40618 in the Additional manuscripts collection at the British Library.

British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius C. II, or the Tiberius Bede, is an 8th-century illuminated manuscript of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum. It is one of only four surviving 8th-century manuscripts of Bede, another of which happens to be MS Cotton Tiberius A. XIV, produced at Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey. As such it is one of the closest texts to Bede's autograph. The manuscript has 155 vellum folios. This manuscript may have been the Latin text on which the Alfredian Old English translation of Bede's Ecclesiastical History was based. The manuscript is decorated with zoomorphic initials in a partly Insular and partly Continental style.

The Vespasian Psalter is an Anglo-Saxon illuminated psalter decorated in a partly Insular style produced in the second or third quarter of the 8th century. It contains an interlinear gloss in Old English which is the oldest extant English translation of any portion of the Bible. It was produced in southern England, perhaps in St. Augustine's Abbey or Christ Church, Canterbury or Minster-in-Thanet, and is the earliest illuminated manuscript produced in "Southumbria" to survive.

British Library, Royal MS 1. B. VII, also called the Royal Athelstan Gospels, is an 8th-century Anglo-Saxon illuminated gospel book. It is closely related to the Lindisfarne Gospels, being either copied from it or from a common model. It is not as lavishly illuminated, and the decoration shows Merovingian influence. The manuscript contains the four Gospels in the Latin Vulgate translation, along with prefatory and explanatory matter. It was presented to Christ Church, Canterbury in the 920s by King Athelstan, who had recorded in a note in Old English (f.15v) that upon his accession to the throne in 925 he had freed one Eadelm and his family from slavery, the earliest recorded manumission in (post-Roman) England.

Koenwald or Cenwald or Coenwald was an Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, probably of Mercian origin.

The Eadwine Psalter or Eadwin Psalter is a heavily illuminated 12th-century psalter named after the scribe Eadwine, a monk of Christ Church, Canterbury, who was perhaps the "project manager" for the large and exceptional book. The manuscript belongs to Trinity College, Cambridge and is kept in the Wren Library. It contains the Book of Psalms in three languages: three versions in Latin, with Old English and Anglo-Norman translations, and has been called the most ambitious manuscript produced in England in the twelfth century. As far as the images are concerned, most of the book is an adapted copy, using a more contemporary style, of the Carolingian Utrecht Psalter, which was at Canterbury for a period in the Middle Ages. There is also a very famous full-page miniature showing Eadwine at work, which is highly unusual and possibly a self-portrait.

The Mac Durnan Gospels or Book of Mac Durnan is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book made in Ireland in the 9th or 10th century, a rather late example of Insular art. Unusually, it was in Anglo-Saxon England soon after it was written, and is now in the collection of Lambeth Palace Library in London.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great. Multiple copies were made of that one original and then distributed to monasteries across England, where they were independently updated. In one case, the Chronicle was still being actively updated in 1154.

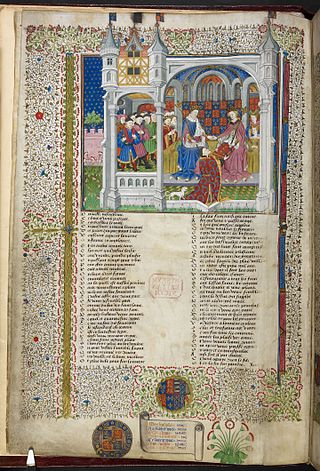

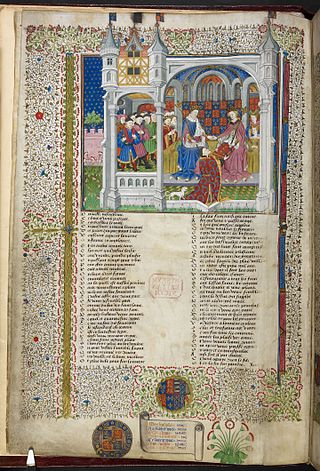

The Royal manuscripts are one of the "closed collections" of the British Library, consisting of some 2,000 manuscripts collected by the sovereigns of England in the "Old Royal Library" and given to the British Museum by George II in 1757. They are still catalogued with call numbers using the prefix "Royal" in the style "Royal MS 2. B. V". As a collection, the Royal manuscripts date back to Edward IV, though many earlier manuscripts were added to the collection before it was donated. Though the collection was therefore formed entirely after the invention of printing, luxury illuminated manuscripts continued to be commissioned by royalty in England as elsewhere until well into the 16th century. The collection was expanded under Henry VIII by confiscations in the Dissolution of the Monasteries and after the falls of Henry's ministers Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. Many older manuscripts were presented to monarchs as gifts; perhaps the most important manuscript in the collection, the Codex Alexandrinus, was presented to Charles I in recognition of the diplomatic efforts of his father James I to help the Eastern Orthodox churches under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. The date and means of entry into the collection can only be guessed at in many if not most cases. Now the collection is closed in the sense that no new items have been added to it since it was donated to the nation.

The so-called Claudius Pontificals are the texts in British Library, Cotton Claudius A.iii, a composite manuscript of three separate pontificals, i.e. compilations of the services reserved for bishops, especially the coronation of kings. The first two date to the 11th century, the third to the 12th century.

The Tiberius Psalter is one of at least four surviving Gallican psalters produced at New Minster, Winchester in the years around the Norman conquest of England. The manuscript can now be seen fully online at the British Library website.