The European eel is a species of eel. They are critically endangered due to overfishing by fisheries on coasts for human consumption and parasites.

The American eel is a facultative catadromous fish found on the eastern coast of North America. Freshwater eels are fish belonging to the elopomorph superorder, a group of phylogenetically ancient teleosts. The American eel has a slender, supple, snake-like body that is covered with a mucus layer, which makes the eel appear to be naked and slimy despite the presence of minute scales. A long dorsal fin runs from the middle of the back and is continuous with a similar ventral fin. Pelvic fins are absent, and relatively small pectoral fins can be found near the midline, followed by the head and gill covers. Variations exist in coloration, from olive green, brown shading to greenish-yellow and light gray or white on the belly. Eels from clear water are often lighter than those from dark, tannic acid streams.

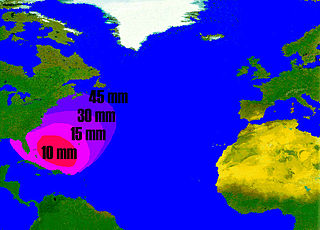

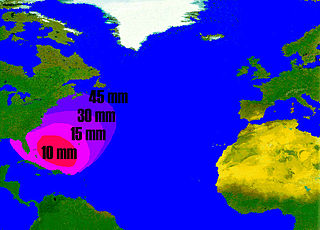

Eels are any of several long, thin, bony fishes of the order Anguilliformes. They have a catadromous life cycle, that is: at different stages of development migrating between inland waterways and the deep ocean. Because fishermen never caught anything they recognized as young eels, the life cycle of the eel is a mystery which has covered a long period of scientific history into the present day. Of significant interest is the search for the spawning grounds for the various species of eels and identifying impacts to population decline in each stage of the life cycle.

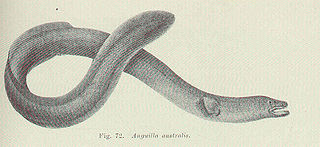

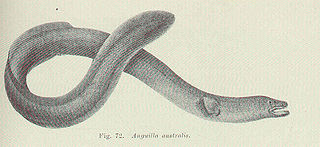

The short-finned eel, also known as the shortfin eel, is one of the 15 species of eel in the family Anguillidae. It is native to the lakes, dams and coastal rivers of south-eastern Australia, New Zealand, and much of the South Pacific, including New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, Lord Howe Island, Tahiti, and Fiji.

Moray eels, or Muraenidae, are a family of eels whose members are found worldwide. There are approximately 200 species in 15 genera which are almost exclusively marine, but several species are regularly seen in brackish water, and a few are found in fresh water.

The Anguillidae are a family of ray-finned fish that contains the freshwater eels. Except from the genus Neoanguilla, with the only known species Neoanguilla nepalensis from Nepal, all the extant species and six subspecies in this family are in the genus Anguilla, and are elongated fish of snake-like bodies, with long dorsal, caudal and anal fins forming a continuous fringe. They are catadromous, spending their adult lives in freshwater, but migrating to the ocean to spawn.

The superorder Elopomorpha contains a variety of types of fishes that range from typical silvery-colored species, such as the tarpons and ladyfishes of the Elopiformes and the bonefishes of the Albuliformes, to the long and slender, smooth-bodied eels of the Anguilliformes. The one characteristic uniting this group of fishes is they all have leptocephalus larvae, which are unique to the Elopomorpha. No other fishes have this type of larvae.

Muraena is a genus of twelve species of large eels in the family Muraenidae.

The New Zealand longfin eel, also known as ōrea, is a species of freshwater eel that is endemic to New Zealand. It is the largest freshwater eel in New Zealand and the only endemic species – the other eels found in New Zealand are the native shortfin eel, also found in Australia, and the naturally introduced Australian longfin eel. Longfin eels are long-lived, migrating to the Pacific Ocean near Tonga to breed at the end of their lives. They are good climbers as juveniles and so are found in streams and lakes a long way inland. An important traditional food source for Māori, who name them ōrea, longfin eel numbers are declining and they are classified as endangered, but over one hundred tonnes are still commercially fished each year.

The speckled longfin eel, Australian long-finned eel or marbled eel is one of 15 species of eel in the family Anguillidae. It has a long snake-like cylindrical body with its dorsal, tail and anal fins joined to form one long fin. It usually has a brownish green or olive green back and sides with small darker spots or blotches all over its body. Its underside is paler. It has a small gill opening on each side of its wide head, with thick lips. It is Australia's largest freshwater eel, and the female usually grows much larger than the male. It is also known as the spotted eel.

The Anguilloidei are a suborder of the order Anguilliformes containing three families:

Anguilla bicolor is a species of eel in the genus Anguilla of the family Anguillidae, consisting of two subspecies.

The mottled eel, also known as the African mottled eel, the Indian longfin eel, the Indian mottled eel, the long-finned eel or the river eel, is a demersal, catadromous eel in the family Anguillidae. It was described by John McClelland in 1844. It is a tropical, freshwater eel which is known from East Africa, Bangladesh, Andaman Islands, Mozambique, Malawi, Sri Lanka, Sumatra, and Indonesia and recently from Madagascar. The eels spend most of their lives in freshwater at a depth range of 3–10 metres, but migrate to the Indian Ocean to breed. Males can reach a maximum total length of 121 centimetres and a maximum weight of 7,000 grams. The eels feed primarily off of benthic crustaceans, mollusks, finfish and worms.

Gymnothorax is a genus of fish in the family Muraenidae found in Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Ocean. With more than 120 species, it the most speciose genus of moray eels.

The giant mottled eel, also known as the marbled eel, is a species of tropical anguillid eel that is found in the Indo-Pacific and adjacent freshwater habitats.

The European conger is a species of conger of the family Congridae. It is the heaviest eel in the world and native to the northeast Atlantic, including the Mediterranean Sea.

Eels are elongated fish, ranging in length from five centimetres (2 in) to four metres (13 ft). Adults range in weight from 30 grams to over 25 kilograms. They possess no pelvic fins, and many species also lack pectoral fins. The dorsal and anal fins are fused with the caudal or tail fin, forming a single ribbon running along much of the length of the animal. Most eels live in the shallow waters of the ocean and burrow into sand, mud, or amongst rocks. A majority of eel species are nocturnal and thus are rarely seen. Sometimes, they are seen living together in holes, or "eel pits". Some species of eels live in deeper water on the continental shelves and over the slopes deep as 4,000 metres (13,000 ft). Only members of the family Anguillidae regularly inhabit fresh water, but they too return to the sea to breed.

The Pacific shortfinned eel, also known as the Pacific shortfinned freshwater eel, the short-finned eel, and the South Pacific eel, is an eel in the family Anguillidae. It was described by Albert Günther in 1871. It is a tropical, freshwater eel which is known from western New Guinea, Queensland, Australia, the Society Islands, and possibly South Africa. The eels spend most of their lives in freshwater, but migrate to the Pacific Ocean to breed. Males can reach a maximum total length of 110 centimetres, but more commonly reach a TL of around 60 cm. The Pacific shortfinned eel is most similar to Anguilla australis, and Anguilla bicolor, but can be distinguished by the number of vertebrae.

Fish go through various life stages between fertilization and adulthood. The life of fish start as spawned eggs which hatch into immotile larvae. These larval hatchlings are not yet capable of feeding themselves and carry a yolk sac which provides stored nutrition. Before the yolk sac completely disappears, the young fish must mature enough to be able to forage independently. When they have developed to the point where they are capable of feeding by themselves, the fish are called fry. When, in addition, they have developed scales and working fins, the transition to a juvenile fish is complete and it is called a fingerling, so called as they are typically about the size of human fingers. The juvenile stage lasts until the fish is fully grown, sexually mature and interacting with other adult fish.

Bathycongrus aequoreus is an eel in the family Congridae. It was described by Charles Henry Gilbert and Frank Cramer in 1897, originally under the genus Congermuraena. It is a marine, deep water-dwelling eel which is known from Hawaii, in the eastern central Pacific Ocean. It dwells at a depth range of 300–686 metres, prefers deeper water and leads a benthic lifestyle.