The Copenhagen criteria are the rules that define whether a country is eligible to join the European Union. The criteria require that a state has the institutions to preserve democratic governance and human rights, has a functioning market economy, and accepts the obligations and intent of the European Union.

An ethnocracy is a type of political structure in which the state apparatus is controlled by a dominant ethnic group to further its interests, power, dominance, and resources. Ethnocratic regimes in the modern era typically display a 'thin' democratic façade covering a more profound ethnic structure, in which ethnicity – and not citizenship – is the key to securing power and resources.

Russians in the Baltic states is a broadly defined subgroup of the Russian diaspora who self-identify as ethnic Russians, or are citizens of Russia, and live in one of the three independent countries – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. As of 2021, there were nearly 900,000 ethnic Russians in the three countries, having declined from ca 1.7 million in 1989, the year of the last census during the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation of the three Baltic countries.

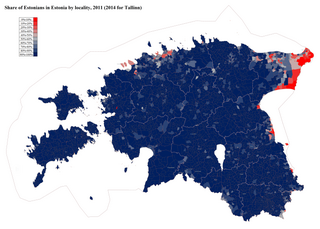

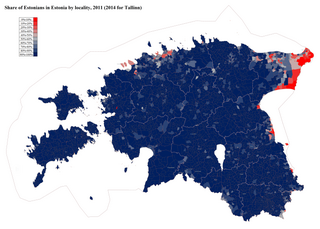

In Estonia, the population of ethnic Russians is estimated at 306,801, most of whom live in the capital city Tallinn and other urban areas of Harju and Ida-Viru counties. While a small settlement of Russian Old Believers on the coast of Lake Peipus has an over 300-year long history, the large majority of the ethnic Russian population in the country originates from the immigration from Russia and other parts of the former USSR during the 1944–1991 Soviet era of Estonia.

The European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) is an academic research institute based in Flensburg, Germany, that conducts research into minority issues, ethnopolitics, and minority-majority relations in Europe. ECMI is a non-partisan and interdisciplinary research institution. It is a non-profit, independent foundation, registered according to German Civil Law.

Palestinian citizens of Israel, also known as 48-Palestinians are citizens of Israel that self-identify as Palestinian. No official statistics exist on this population; according to Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics, the Arab population in 2023 was estimated at 2,080,000, representing 21.1% of the country's population.

Estonia–Russia relations are the bilateral foreign relations between Estonia and Russia. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were established on 2 February 1920 after the Estonian War of Independence ended in Estonian victory with Russia recognizing Estonia's sovereignty and renounced any and all territorial claims on Estonia.

The Intermovement(International Movement of Workers in the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic) was a political movement and organisation in the Estonian SSR. It was founded on 19 July 1988 and claimed by different sources 16,000 - 100,000 members. The original name of the movement was Interfront, which was changed to Intermovement in autumn 1988.

The concept of demographic threat is a term used in political conversation or demography to refer to population increases from within a minority ethnic or religious group in a given country that is perceived as threatening to the ethnic, racial or religious majority, stability of the country or to the identity of said countries in which it is present in.

Non-citizens or aliens in Latvian law are individuals who are not citizens of Latvia or any other country, but who, in accordance with the Latvian law "Regarding the status of citizens of the former USSR who possess neither Latvian nor other citizenship," have the right to a non-citizen passport issued by the Latvian government as well as other specific rights. Approximately two thirds of them are ethnic Russians, followed by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, and Lithuanians.

Oren Yiftachel is an Israeli professor of political and legal geography, urban studies and urban planning at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, in Beersheba. He holds the Lynn and Lloyd Hurst Family Chair in Urban Studies.

Human rights in Latvia are generally respected by the government, according to the US Department of State and Freedom House. Latvia is ranked above-average among the world's sovereign states in democracy, press freedom, privacy and human development. The country has a relatively large ethnic Russian community, which has basic rights guaranteed under the constitution and international human rights laws ratified by the Latvian government.

The main ethnic minorities in Georgia are Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Ukrainians, Russians, Greeks, Abkhazians, Ossetians, Kists, Assyrians and Yazidi.

Al-Ard was a Palestinian political movement made up of Arab citizens of Israel. It was active between 1958 and some time in the 1970s.

Human rights in Estonia are acknowledgedas being generally respected by the government. Nevertheless, there are concerns in some areas, such as detention conditions, excessive police use of force, and child abuse. Estonia has been classified as a flawed democracy, with moderate privacy and human development in Europe. Individuals are guaranteed on paper the basic rights under the constitution, legislative acts, and treaties relating to human rights ratified by the Estonian government. As of 2023, Estonia was ranked 8th in the world by press freedoms.

Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People, informally known as the Nation-State Bill or the Nationality Bill, is an Israeli Basic Law that specifies the country's significance to the Jewish people. It was passed by the Knesset—with 62 in favour, 55 against, and two abstentions—on 19 July 2018 and is largely symbolic and declarative in nature. The law outlines a number of roles and responsibilities by which Israel is bound in order to fulfill the purpose of serving as the Jews' nation-state. However, it was met with sharp backlash internationally and has been characterized as racist and undemocratic by some critics. After it was passed, several groups in the Jewish diaspora expressed concern that it was actively violating Israel's self-defined legal status as a "Jewish and democratic state" in exchange for adopting an exclusively Jewish identity. The European Union stated that the Nation-State Bill had complicated the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, while the Arab League, the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and the Muslim World League condemned it as a manifestation of apartheid.

"Jewish and democratic state" is the Israeli legal definition of the nature and character of the State of Israel. The "Jewish" nature was first defined within the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May 1948. The "democratic" character was first officially added in the amendment to Israel's Basic Law: The Knesset, which was passed in 1985.

Sammy Smooha is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Haifa.

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric approach to various political issues related to national affirmation of a particular ethnic group.