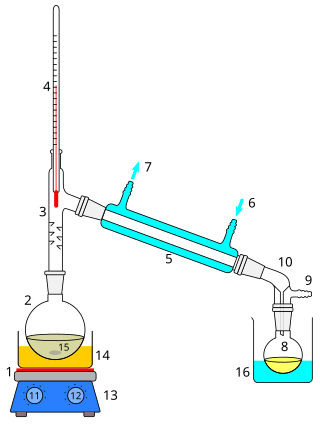

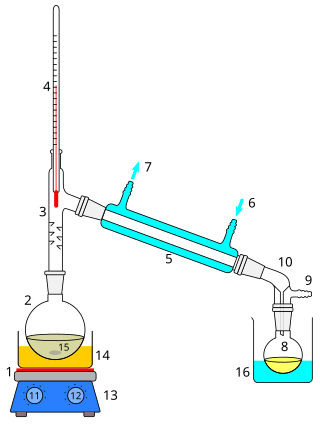

Distillation, also classical distillation, is the process of separating the component substances of a liquid mixture of two or more chemically discrete substances; the separation process is realized by way of the selective boiling of the mixture and the condensation of the vapors in a still.

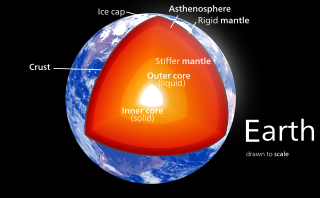

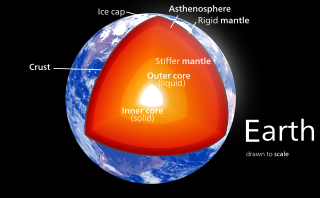

Magma is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural satellites. Besides molten rock, magma may also contain suspended crystals and gas bubbles.

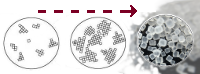

Zone melting is a group of similar methods of purifying crystals, in which a narrow region of a crystal is melted, and this molten zone is moved along the crystal. The molten region melts impure solid at its forward edge and leaves a wake of purer material solidified behind it as it moves through the ingot. The impurities concentrate in the melt, and are moved to one end of the ingot. Zone refining was invented by John Desmond Bernal and further developed by William G. Pfann in Bell Labs as a method to prepare high-purity materials, mainly semiconductors, for manufacturing transistors. Its first commercial use was in germanium, refined to one atom of impurity per ten billion, but the process can be extended to virtually any solute–solvent system having an appreciable concentration difference between solid and liquid phases at equilibrium. This process is also known as the float zone process, particularly in semiconductor materials processing.

Phosphoric acid is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula H3PO4. It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solution, which is a colourless, odourless, and non-volatile syrupy liquid. It is a major industrial chemical, being a component of many fertilizers.

Freezing is a phase transition where a liquid turns into a solid when its temperature is lowered below its freezing point. In accordance with the internationally established definition, freezing means the solidification phase change of a liquid or the liquid content of a substance, usually due to cooling.

Sublimation is the transition of a substance directly from the solid to the gas state, without passing through the liquid state. The verb form of sublimation is sublime, or less preferably, sublimate. Sublimate also refers to the product obtained by sublimation. The point at which sublimation occurs rapidly is called critical sublimation point, or simply sublimation point. Notable examples include sublimation of dry ice at room temperature and atmospheric pressure, and that of solid iodine with heating.

Fractional freezing is a process used in process engineering and chemistry to separate substances with different melting points. It can be done by partial melting of a solid, for example in zone refining of silicon or metals, or by partial crystallization of a liquid, as in freeze distillation, also called normal freezing or progressive freezing. The initial sample is thus fractionated.

Fractionation is a separation process in which a certain quantity of a mixture is divided during a phase transition, into a number of smaller quantities (fractions) in which the composition varies according to a gradient. Fractions are collected based on differences in a specific property of the individual components. A common trait in fractionations is the need to find an optimum between the amount of fractions collected and the desired purity in each fraction. Fractionation makes it possible to isolate more than two components in a mixture in a single run. This property sets it apart from other separation techniques.

Crystallization is the process by which solid forms, where the atoms or molecules are highly organized into a structure known as a crystal. Some ways by which crystals form are precipitating from a solution, freezing, or more rarely deposition directly from a gas. Attributes of the resulting crystal depend largely on factors such as temperature, air pressure, and in the case of liquid crystals, time of fluid evaporation.

The Betterton-Kroll Process is a pyrometallurgical process for refining lead from lead bullion. Developed by William Justin Kroll in 1922, the Betterton–Kroll process is one of the final steps in conventional lead smelting. After gold, copper, and silver are removed from the lead, significant amounts of bismuth and antimony remain. The Betterton–Kroll process is used to remove these impurities. In the process, calcium and magnesium are added to the molten lead at temperatures around 380 °C. The calcium and magnesium react with the bismuth and antimony in the bullion to form alloys with a higher melting point, which then can be skimmed off of the surface. This process leaves behind lead with less than 0.01 percent bismuth by weight. The process is crucial to cheap industrial lead smelting and offers significant advantages over more expensive processes like the Betts Electrolytic process and fractional crystallization.

A phase-change material (PCM) is a substance which releases/absorbs sufficient energy at phase transition to provide useful heat or cooling. Generally the transition will be from one of the first two fundamental states of matter - solid and liquid - to the other. The phase transition may also be between non-classical states of matter, such as the conformity of crystals, where the material goes from conforming to one crystalline structure to conforming to another, which may be a higher or lower energy state.

Downstream processing refers to the recovery and the purification of biosynthetic products, particularly pharmaceuticals, from natural sources such as animal tissue, plant tissue or fermentation broth, including the recycling of salvageable components as well as the proper treatment and disposal of waste. It is an essential step in the manufacture of pharmaceuticals such as antibiotics, hormones, antibodies and vaccines; antibodies and enzymes used in diagnostics; industrial enzymes; and natural fragrance and flavor compounds. Downstream processing is usually considered a specialized field in biochemical engineering, which is itself a specialization within chemical engineering. Many of the key technologies were developed by chemists and biologists for laboratory-scale separation of biological and synthetic products, whilst the role of biochemical and chemical engineers is to develop the technologies towards larger production capacities.

In geology, igneous differentiation, or magmatic differentiation, is an umbrella term for the various processes by which magmas undergo bulk chemical change during the partial melting process, cooling, emplacement, or eruption. The sequence of magmas produced by igneous differentiation is known as a magma series.

The flux method is a crystal growth method where starting materials are dissolved in a solvent (flux), and are precipitated out to form crystals of a desired compound. The flux lowers the melting point of the desired compound, analogous to a wet chemistry recrystallization. The flux is molten in a highly stable crucible that does not react with the flux. Metal crucibles, such as platinum, titanium, and niobium are used for the growth of oxide crystals. Ceramic crucibles, such as alumina, zirconia, and boron nitride are used for the growth of metallic crystals. For air-sensitive growths, contents are sealed in ampoules or placed in atmosphere controlled furnaces.

Winterizationof oil is a process that uses a solvent and cold temperatures to separate lipids and other desired oil compounds from waxes. Winterization is a type of fractionation, the general process of separating the triglycerides found in fats and oils, using the difference in their melting points, solubility, and volatility.

In chemistry, recrystallization is a technique used to purify chemicals. By dissolving a mixture of a compound and impurities in an appropriate solvent, either the desired compound or impurities can be removed from the solution, leaving the other behind. It is named for the crystals often formed when the compound precipitates out. Alternatively, recrystallization can refer to the natural growth of larger ice crystals at the expense of smaller ones.

Pumpable icetechnology (PIT) uses thin liquids, with the cooling capacity of ice. Pumpable ice is typically a slurry of ice crystals or particles ranging from 5 micrometers to 1 cm in diameter and transported in brine, seawater, food liquid, or gas bubbles of air, ozone, or carbon dioxide.

A crystal mush is magma that contains a significant amount of crystals suspended in the liquid phase (melt). As the crystal fraction makes up less than half of the volume, there is no rigid large-scale three-dimensional network as in solids. As such, their rheological behavior mirrors that of absolute liquids.

While chemically pure materials have a single melting point, chemical mixtures often partially melt at the solidus temperature (TS or Tsol), and fully melt at the higher liquidus temperature (TL or Tliq). The solidus is always less than or equal to the liquidus, but they need not coincide. If a gap exists between the solidus and liquidus it is called the freezing range, and within that gap, the substance consists of a mixture of solid and liquid phases (like a slurry). Such is the case, for example, with the olivine (forsterite-fayalite) system, which is common in Earth's mantle.