Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness is a qualitative ordinal scale characterizing scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material. Created in 1812 by German geologist and mineralogist Friedrich Mohs, it is one of several definitions of hardness in materials science, some of which are more quantitative. The method of comparing hardness by observing which minerals can scratch others is of great antiquity, having been mentioned by Theophrastus in his treatise On Stones, c. 300 BC, followed by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia, c. 77 AD. While greatly facilitating the identification of minerals in the field, the Mohs scale does not show how well hard materials perform in an industrial setting.

Topaz is a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine with the chemical formula Al2SiO4(F, OH)2. Topaz crystallizes in the orthorhombic system, and its crystals are mostly prismatic terminated by pyramidal and other faces. It is one of the hardest naturally occurring minerals (Mohs hardness of 8) and is the hardest of any silicate mineral. This hardness combined with its usual transparency and variety of colors means that it has acquired wide use in jewellery as a cut gemstone as well as for intaglios and other gemstone carvings.

A natural arch, natural bridge, or rock arch is a natural rock formation where an arch has formed with an opening underneath. Natural arches commonly form where inland cliffs, coastal cliffs, fins or stacks are subject to erosion from the sea, rivers or weathering.

Badlands are a type of dry terrain where softer sedimentary rocks and clay-rich soils have been extensively eroded by wind and water. They are characterized by steep slopes, minimal vegetation, lack of a substantial regolith, and high drainage density. They can resemble malpaís, a terrain of volcanic rock. Canyons, ravines, gullies, buttes, mesas, hoodoos and other such geologic forms are common in badlands. They are often difficult to navigate by foot. Badlands often have a spectacular color display that alternates from dark black/blue coal stria to bright clays to red scoria.

A stack or sea stack is a geological landform consisting of a steep and often vertical column or columns of rock in the sea near a coast, formed by wave erosion. Stacks are formed over time by wind and water, processes of coastal geomorphology. They are formed when part of a headland is eroded by hydraulic action, which is the force of the sea or water crashing against the rock. The force of the water weakens cracks in the headland, causing them to later collapse, forming free-standing stacks and even a small island. Without the constant presence of water, stacks also form when a natural arch collapses under gravity, due to sub-aerial processes like wind erosion. Erosion causes the arch to collapse, leaving the pillar of hard rock standing away from the coast—the stack. Eventually, erosion will cause the stack to collapse, leaving a stump. Stacks can provide important nesting locations for seabirds, and many are popular for rock climbing.

Natural Bridges National Monument is a U.S. National Monument located about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of the Four Corners boundary of southeast Utah, in the western United States, at the junction of White Canyon and Armstrong Canyon, part of the Colorado River drainage. It features the thirteenth largest natural bridge in the world, carved from the white Permian sandstone of the Cedar Mesa Formation that gives White Canyon its name.

The exposed geology of the Bryce Canyon area in Utah shows a record of deposition that covers the last part of the Cretaceous Period and the first half of the Cenozoic era in that part of North America. The ancient depositional environment of the region around what is now Bryce Canyon National Park varied from the warm shallow sea in which the Dakota Sandstone and the Tropic Shale were deposited to the cool streams and lakes that contributed sediment to the colorful Claron Formation that dominates the park's amphitheaters.

A hoodoo is a tall, thin spire of rock that protrudes from the bottom of an arid drainage basin or badland. Hoodoos typically consist of relatively soft rock topped by harder, less easily eroded stone that protects each column from the elements. They generally form within sedimentary rock and volcanic rock formations.

Chrysocolla is a hydrated copper phyllosilicate mineral with formula: Cu2−xAlx(H2−xSi2O5)(OH)4·nH2O (x<1) or (Cu,Al)2H2Si2O5(OH)4·nH2O. The structure of the mineral has been questioned, as spectrographic studies suggest material identified as chrysocolla may be a mixture of the copper hydroxide spertiniite and chalcedony.

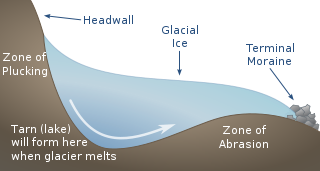

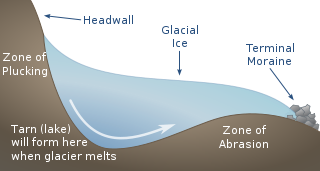

Plucking, also referred to as quarrying, is a glacial phenomenon that is responsible for the erosion and transportation of individual pieces of bedrock, especially large "joint blocks". This occurs in a type of glacier called a "valley glacier". As a glacier moves down a valley, friction causes the basal ice of the glacier to melt and infiltrate joints (cracks) in the bedrock. The freezing and thawing action of the ice enlarges, widens, or causes further cracks in the bedrock as it changes volume across the ice/water phase transition, gradually loosening the rock between the joints. This produces large pieces of rock called joint blocks. Eventually these joint blocks come loose and become trapped in the glacier.

An exhumed river channel is a ridge of sandstone that remains when the softer flood plain mudstone is eroded away. The process begins with the deposition of sand within a river channel and mud on the adjacent floodplain. Eventually the channel is abandoned and over time becomes buried by flood deposits from other channels. Because the sand is porous, groundwater flows more easily through the sand than through the mud of the floodplain deposits.

In structural geology, a homocline or homoclinal structure, is a geological structure in which the layers of a sequence of rock strata, either sedimentary or igneous, dip uniformly in a single direction having the same general inclination in terms of direction and angle. A homocline can be associated with either one limb of a fold, the edges of a dome, the coast-ward tilted strata underlying a coastal plain, slice of thrust fault, or a tilted fault block. When the homoclinal strata consists of alternating layers of rock that vary hardness and resistance to erosion, their erosion produces either cuestas, homoclinal ridges, or hogbacks depending on the angle of dip of the strata. On a topographic map, the landfroms associated with homoclines exhibit nearly parallel elevation contour lines that show a steady change in elevation in a given direction. In the subsurface, they characterize by parallel structural contour lines.

In geomorphology, geography and geology, a bench or benchland is a long, relatively narrow strip of relatively level or gently inclined land that is bounded by distinctly steeper slopes above and below it. Benches can be of different origins and created by very different geomorphic processes.

Inverted relief, inverted topography, or topographic inversion refers to landscape features that have reversed their elevation relative to other features. It most often occurs when low areas of a landscape become filled with lava or sediment that hardens into material that is more resistant to erosion than the material that surrounds it. Differential erosion then removes the less resistant surrounding material, leaving behind the younger resistant material, which may then appear as a ridge where previously there was a valley. Terms such as "inverted valley" or "inverted channel" are used to describe such features. Inverted relief has been observed on the surfaces of other planets as well as on Earth. For example, well-documented inverted topographies have been discovered on Mars.

The early Late Triassic conglomerate called the Shinarump Conglomerate, formally the Shinarump Member of the Chinle Formation, is a highly resistant coarse-grained sandstone and pebble conglomerate, sometimes forming a caprock because of its hardness, cementation, and erosion resistance. The Shinarump is found throughout the Colorado Plateau with significant exposures as the canyon rimrock in the vicinity of Canyon De Chelly National Monument, at the north-northeast of the Defiance Plateau/Defiance Uplift. At Canyon De Chelly the Shinarump Conglomerate was laid down upon De Chelly Sandstone-(280 Ma, an erosion unconformity of 50 my), in a region at the west foothill region of the mostly north-south trending Chuska Mountains of northeast Arizona – northwest New Mexico.

The Eureka Quartzite is an extensive Paleozoic marine sandstone deposit in western North America that is notable for its great extent, extreme purity, consistently fine grain size of Quartzite, and its tendency to form conspicuous white cliffs visible from afar.

Grayite, ThPO4 • (H2O), is a thorium phosphate mineral of the Rabdophane group first discovered in 1957 by S.H.U. Bowie in Rhodesia. It is of moderate hardness occurring occasionally in aggregates of hexagonal crystals occasionally but more commonly in microgranular/cryptocrystalline masses. Due to its thorium content, grayite displays some radioactivity although it is only moderate and the mineral displays powder XRD peaks without any metamict-like effects. The color of grayite is most commonly observed as a light to dark reddish brown but has also been observed as lighter yellows with grayish tints. It has a low to moderate hardness with a Mohs hardness of 3-4 and has a specific gravity of 3.7-4.3. It has been found in both intrusive igneous and sedimentary environments.

The geology of Colorado was assembled from island arcs accreted onto the edge of the ancient Wyoming Craton. The Sonoma orogeny uplifted the ancestral Rocky Mountains in parallel with the diversification of multicellular life. Shallow seas covered the regions, followed by the uplift current Rocky Mountains and intense volcanic activity. Colorado has thick sedimentary sequences with oil, gas and coal deposits, as well as base metals and other minerals.