The Ayyubid dynasty was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Kurdish origin, founded by Saladin and centered in Egypt, ruling over the Levant, Mesopotamia, Hijaz, Nubia and parts of the Maghreb. The dynasty ruled large parts of the Middle East during the 12th and 13th centuries. Saladin had risen to vizier of Fatimid Egypt in 1169, before abolishing the Fatimid Caliphate in 1171. Three years later, he was proclaimed sultan following the death of his former master, the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din and established himself as the first custodian of the two holy mosques. For the next decade, the Ayyubids launched conquests throughout the region and by 1183, their domains encompassed Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, the Hejaz, Yemen and the North African coast up to the borders of modern-day Tunisia. Most of the Crusader states including the Kingdom of Jerusalem fell to Saladin after his victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, the Crusaders regained control of Palestine's coastline in the 1190s.

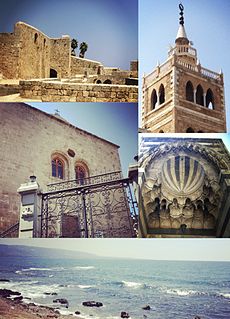

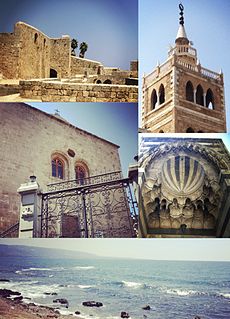

Tripoli is the largest city in northern Lebanon and the second-largest city in the country. Situated 85 kilometers north of the capital Beirut, it is the capital of the North Governorate and the Tripoli District. Tripoli overlooks the eastern Mediterranean Sea, and it is the northernmost seaport in Lebanon. It holds a string of four small islands offshore, and they are the only islands in Lebanon. The Palm Islands were declared a protected area because of their status of haven for endangered loggerhead turtles, rare monk seals and migratory birds. Tripoli borders the city of El Mina, the port of the Tripoli District, which it is geographically conjoined with to form the greater Tripoli conurbation.

Krak des Chevaliers, also called Crac des Chevaliers, Ḥiṣn al-Akrād, and formerly Crac de l'Ospital, is a Crusader castle in Syria and one of the most important preserved medieval castles in the world. The site was first inhabited in the 11th century by Kurdish troops garrisoned there by the Mirdasids. In 1142 it was given by Raymond II, Count of Tripoli, to the order of the Knights Hospitaller. It remained in their possession until it fell in 1271.

Safita is a city in the Tartous Governorate, northwestern Syria, located to the southeast of Tartous and to the northwest of Krak des Chevaliers. It is situated on the tops of three hills and the valleys between them, in the Syrian Coastal Mountain Range. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Safita had a population of 20,301 in the 2004 census.

The Ma'n dynasty, also known as the Ma'nids, were an Arab family of Druze chiefs based in the Chouf area in southern Mount Lebanon who were politically prominent in the 12th and 15th–17th centuries.

The Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles, also known as Qala'at Sanjil and Qala'at Tarablus in Arabic, is a citadel and fort on a hilltop in Tripoli, Lebanon. It takes its name from Raymond de Saint-Gilles, the Count of Toulouse and Crusader commander who was a key player in its enlargement. It is a common misconception that he was responsible for its construction when in 1103 he laid siege to the city.

Tripoli Eyalet was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. The capital was in Tripoli. Its reported area in the 19th century was 1,629 square miles (4,220 km2).

Damascus Eyalet was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. Its reported area in the 19th century was 51,900 square kilometres (20,020 sq mi). It became an eyalet after the Ottomans conquered it from the Mamluks in 1516. Janbirdi al-Ghazali, a Mamluk traitor, was made the first beylerbey of Damascus. The Damascus Eyalet was one of the first Ottoman provinces to become a vilayet after an administrative reform in 1865, and by 1867 it had been reformed into the Syria Vilayet.

Baarin is a village in northern Syria, administratively part of the Hama Governorate, located in Homs Gap roughly 38 kilometers (24 mi) southwest of Hama. Nearby localities include Taunah and Awj to the south, Aqrab and Houla to the southeast, Nisaf, Ayn Halaqim and Wadi al-Uyun to the west, Masyaf, Deir Mama and Mahrusah to the north, and Deir al-Fardis and al-Rastan to the east. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Baarin had a population of 5,559 in the 2004 census. Baarin is also the largest locality in the Awj nahiyah ("subdistrict") which comprises thirteen villages with a population of 33,344. The village's inhabitants are predominantly Alawites.

Kafartab was a town and fortress in northwestern Syria that existed during the medieval period between the fortress cities of Maarat al-Numan in the north and Shaizar to the south. It was situated along the southeastern slopes of Jabal al-Zawiya. According to French geographer Robert Boulanger, writing in the early 1940s, Kafartab was "an abandoned ancient site" located 2.5 mi (4.0 km) northwest of Khan Shaykhun.

Ghazir is a town and municipality in the Keserwan District of the Mount Lebanon Governorate of Lebanon. It is located 27 kilometres (17 mi) north of Beirut. It has an average elevation of 380 meters above sea level and a total land area of 542 hectares (2.09 sq mi). The town has four schools, two public and two private, with a total of 3,253 students as of 2008. Ghazir's name is derived from Arabic root words for "heavy rains", and the town is known for its numerous groundwater reserves. Ghazir is divided into three major parts: Ghazir el-Fawka, Central Ghazir, and Kfarhbab. The inhabitants of Ghazir are predominantly Maronite Catholics.

The Assaf dynasty were a Sunni Muslim and ethnic Turkmen dynasty of chieftains based in the Keserwan region of Mount Lebanon in the 14th–16th centuries. They came to the aforementioned area in 1306 after being assigned by the Bahri Mamluks to guard the coastal region between Beirut and Byblos and to check the power of the mostly Shia Muslim population at the time. During this period, they established their headquarters in Ghazir, which served as the Assafs' base throughout their rule.

Al-Rahba, also known as Qal'at al-Rahba, which translates as the "Citadel of al-Rahba", is a medieval Arab fortress on the west bank of the Euphrates River, adjacent to the city of Mayadin in Syria. Situated atop a mound with an elevation of 244 meters (801 ft), al-Rahba oversees the Syrian Desert steppe. It has been described as "a fortress within a fortress"; it consists of an inner keep measuring 60 by 30 meters, protected by an enclosure measuring 270 by 95 meters. Al-Rahba is largely in ruins today as a result of wind erosion.

Yusuf Sayfa Pasha was a chieftain and multazim in the Tripoli region who frequently served as the Ottoman beylerbey of Tripoli Eyalet between 1579 and his death.

The Banu Ammar were a family of Muslim magistrates (qadis) who ruled the city of Tripoli in what is now Lebanon from 1070 until 1109.

The Buhturids, also known as the Banu Buhtur or the Tanukh, were a clan whose chiefs served as the emirs (commanders) of the Gharb area southeast of Beirut in Mount Lebanon in the 12th–15th centuries. A branch of the Tanukhid tribal confederation, they were established in the Gharb by the Muslim atabegs of Damascus following the capture of Beirut by the Crusaders in 1110 to guard the mountainous frontier between the Crusader coastlands and the Islamic interior of the Levant. They were granted iqtas over villages in the Gharb and command over its peasant warriors, who subscribed to the Druze religion, which the Buhturids professed. Their iqtas were successively confirmed, decreased or increased by the Burid, Zengid, Ayyubid and Mamluk rulers of Damascus in return for military service and intelligence gathering in the war with the Crusader lordships of Beirut and Sidon. In times of peace the Buhturids maintained working relations with the Crusaders.

Akkar al-Atika is a town and municipality located in the Akkar Governorate in northern Lebanon. It is about 135 kilometres (84 mi) north of Beirut. Akkar al-Atika contains the 11th-century fortress of Gibelacar, which was utilized by the Crusaders and became the headquarters of the Sayfa clan, whose members were chieftains and Ottoman governors of Tripoli and its districts in from the late 16th until the mid-17th centuries.

The 1585 Ottoman expedition against the Druze, also called the 1585 Ottoman invasion of the Shuf, was an Ottoman military campaign led by Ibrahim Pasha against the Druze and other chieftains of Mount Lebanon and its environs, then a part of the Sidon-Beirut Sanjak of the province of Damascus Eyalet. It had been traditionally considered the direct consequence of a raid by bandits in Akkar against the tribute caravan of Ibrahim Pasha, then Egypt's outgoing governor, who was on his way to Constantinople. Modern research indicates that the tribute caravan arrived intact and that the expedition was instead the culmination of Ottoman attempts to subjugate the Druze and other tribal groups in Mount Lebanon dating from 1518.

The Alam al-Dins, also spelled Alamuddin or Alameddine, were a Druze family that intermittently held or contested the paramount chieftainship of the Druze districts of Mount Lebanon in opposition to the Ma'n and Shihab families in the late 17th–early 18th centuries during Ottoman rule. Their origins were obscure with different accounts claiming or proposing Tanukhid or Ma'nid ancestry. From at least the early 17th century they were the traditional leaders of the Yaman faction among the Druzes, which stood in opposition to the Qays, led by the Tanukhid Buhturs, traditional chiefs of the Gharb area south of Beirut, and the Ma'ns. A likely chief of the family, Muzaffar al-Andari, led the Druze opposition to the powerful Ma'nid leader Fakhr al-Din II until reconciling with him in 1623.

The Sawwaf were a Druze family of chiefs active in Mount Lebanon and Wadi al-Taym in the late 15th–early 18th centuries. They were based in the Matn area and historically opposed the Ma'n dynasty and Shihab dynasty. They were the eliminated by the latter at the Battle of Ain Dara in 1711.