The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States is a treaty signed at Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 26, 1933, during the Seventh International Conference of American States. The Convention codifies the declarative theory of statehood as accepted as part of customary international law. At the conference, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull declared the Good Neighbor Policy, which opposed U.S. armed intervention in inter-American affairs. The convention was signed by 19 states. The acceptance of three of the signatories was subject to minor reservations. Those states were Brazil, Peru and the United States.

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina, nicknamed El Jefe ), was a Dominican military commander and was a dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from August 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He served as president from 1930 to 1938 and again from 1942 to 1952, ruling for the rest of his life as an unelected military strongman under figurehead presidents. His rule of 31 years, known to Dominicans as the Trujillo Era, was one of the longest for a non-royal leader in the world, and centered around a personality cult of the ruling family. It was also one of the most brutal; Trujillo's security forces, including the infamous SIM, were responsible for perhaps as many as 50,000 murders. These included between 12,000 and 30,000 Haitians in the infamous Parsley massacre in 1937, which continues to affect Dominican-Haitian relations to this day.

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his State of the Union address in 1904 after the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. The corollary states that the United States could intervene in the internal affairs of Latin American countries if they committed flagrant wrongdoings that "loosened the ties of civilized society".

The Good Neighbor policy was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin Roosevelt towards Latin America. Although the policy was implemented by the Roosevelt administration, President Woodrow Wilson had previously used the term, but subsequently went on to justify U.S. involvement in the Mexican Revolution and occupation of Haiti. Senator Henry Clay had coined the term Good Neighbor in the previous century. President Herbert Hoover turned against interventionism and developed policies that Roosevelt perfected.

Benjamin Sumner Welles was an American government official and diplomat. He was a major foreign policy adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and served as Under Secretary of State from 1936 to 1943, during Roosevelt's presidency.

The Clark Memorandum on the Monroe Doctrine or Clark Memorandum, written on December 17, 1928 by Calvin Coolidge's undersecretary of state J. Reuben Clark, concerned the United States' use of military force to intervene in Latin American nations. This memorandum was a secret until it was officially released in 1930 by the Herbert Hoover administration.

The Havana Conference was a conference held in the Cuban capital, Havana, from July 21 to July 30, 1940. At the meeting by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the United States, Panama, Mexico, Ecuador, Cuba, Costa Rica, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay, Honduras, Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Brazil, Bolivia, Haiti and El Salvador agreed to collectively govern territories of nations that were taken over by the Axis powers of World War II and also declared that an attack on any nation in the region would be considered as an attack on all nations.

The Johnson Doctrine, enunciated by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson after the United States' intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965, declared that domestic revolution in the Western Hemisphere would no longer be a local matter when the object is the establishment of a "Communist dictatorship". During Johnson's presidency, the United States again began interfering in the affairs of sovereign nations, particularly Latin America. The Johnson Doctrine is the formal declaration of the intention of the United States to intervene in such affairs. It is an extension of the Eisenhower and Kennedy Doctrines.

Pan-Americanism is a movement that seeks to create, encourage, and organize relationships, an association, and cooperation among the states of the Americas, through diplomatic, political, economic, and social means.

Thomas Clifton Mann was an American diplomat who specialized in Latin American affairs. He entered the U.S. Department of State in 1942 and quickly rose through the ranks to become an influential establishment figure. He worked to influence the internal affairs of numerous Latin American nations, typically focusing on economic and political influence rather than direct military intervention. After Lyndon B. Johnson became President in 1963, Mann received a double appointment and was recognized as the U.S. authority on Latin America. In March 1964, Mann outlined a policy of supporting regime change and promoting the economic interests of U.S. businesses. This policy, which moved away from the political centrism of Kennedy's Alliance for Progress, has been called the Mann Doctrine. Mann left the State Department in 1966 and became a spokesperson for the Automobile Manufacturer's Association.

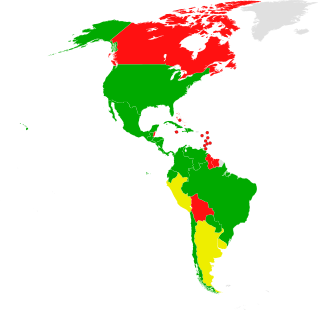

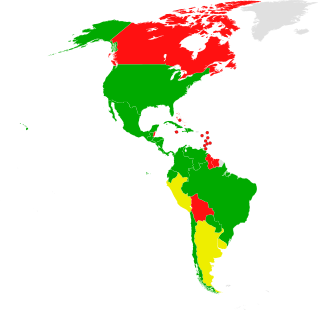

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934. The military interventions were primarily carried out by the United States Marine Corps, which also developed a manual, the Small Wars Manual (1921) based on their experiences. On occasion, the United States Navy provided gunfire support and the United States Army also deployed troops.

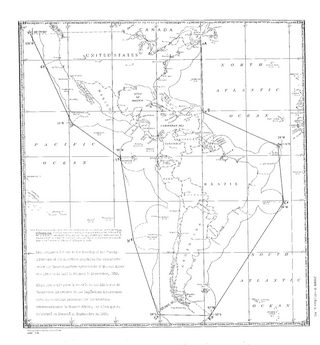

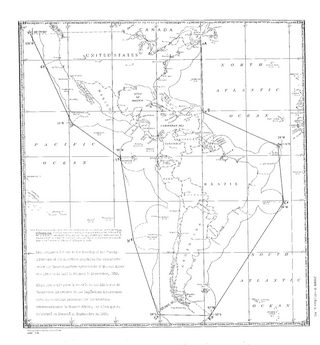

The Monroe Doctrine is a United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers is a potentially hostile act against the United States. The doctrine was central to American grand strategy in the 20th century.

Historically speaking, bilateral relations between the various countries of Latin America and the United States of America have been multifaceted and complex, at times defined by strong regional cooperation and at others filled with economic and political tension and rivalry. Although relations between the U.S. government and most of Latin America were limited prior to the late 1800s, for most of the past century, the United States has unofficially regarded parts of Latin America as within its sphere of influence, and for much of the Cold War (1947–1991), actively vied with the Soviet Union for influence in the Western Hemisphere.

Argentina and the United States have maintained bilateral relations since the United States formally recognized the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, the predecessor to Argentina, on January 27, 1823.

Dominican Republic–United States relations are bilateral relations between the Dominican Republic and the United States of America. There are around 200,000 Americans expats in the Dominican Republic, and a little over 2 million Dominicans live in the United States.

The Cuban–American Treaty of Relations took effect on June 9, 1934. It abrogated the Treaty of Relations of 1903.

The Panama Conference was a meeting by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the United States, Panama, Mexico, Ecuador, Cuba, Costa Rica, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay, Honduras, Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Brazil, Bolivia, Haiti and El Salvador in Panama City at the Republic of Panama on September 23, 1939, shortly after the beginning of World War II in Europe.

During World War II, a number of significant economic, political, and military changes took place in Latin America. The war caused considerable panic in the region over economics as large portions of economy of the region depended on the European investment capital, which was shut down. Latin America tried to stay neutral at first but the warring countries were endangering their neutrality. In order to better protect the Panama Canal, combat Axis influence, and optimize the production of goods for the war effort, the United States through Lend-Lease and similar programs greatly expanded its interests in Latin America, resulting in large-scale modernization and a major economic boost for the countries that participated.

The foreign policy of the United States was controlled personally by Franklin D. Roosevelt during his first and second and third and fourth terms as the president of the United States from 1933 to 1945. He depended heavily on Henry Morgenthau Jr., Sumner Welles, and Harry Hopkins. Meanwhile, Secretary of State Cordell Hull handled routine matters. Roosevelt was an internationalist, while powerful members of Congress favored more isolationist solutions in order to keep the U.S. out of European wars. There was considerable tension before the Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The attack converted the isolationists or made them irrelevant. The US began aid to the Soviet Union after Germany invaded it in June 1941. After the US declared war in December 1941, key decisions were made at the highest level by Roosevelt, Britain's Winston Churchill and the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin, along with their top aides. After 1938 Washington's policy was to help China in its war against Japan, including cutting off money and oil to Japan. While isolationism was powerful regarding Europe, American public and elite opinion strongly opposed Japan.

Foreign policy of Herbert Hoover covers the international activities and policies of Herbert Hoover for his entire career, with emphasis to his roles from 1914 to 1933.