Gneiss is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures and pressures than schist. Gneiss nearly always shows a banded texture characterized by alternating darker and lighter colored bands and without a distinct cleavage.

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Schist is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes or plates. This texture reflects a high content of platy minerals, such as micas, talc, chlorite, or graphite. These are often interleaved with more granular minerals, such as feldspar or quartz.

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2Si2O5(OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especially quartz and calcite. Shale is characterized by its tendency to split into thin layers (laminae) less than one centimeter in thickness. This property is called fissility. Shale is the most common sedimentary rock.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Migmatite is a composite rock found in medium and high-grade metamorphic environments, commonly within Precambrian cratonic blocks. It consists of two or more constituents often layered repetitively: one layer is an older metamorphic rock that was reconstituted subsequently by partial melting ("neosome"), while the alternate layer has a pegmatitic, aplitic, granitic or generally plutonic appearance ("paleosome"). Commonly, migmatites occur below deformed metamorphic rocks that represent the base of eroded mountain chains.

The Llano Uplift is a geologically ancient, low geologic dome that is about 90 miles (140 km) in diameter and located mostly in Llano, Mason, San Saba, Gillespie, and Blanco counties, Texas. It consists of an island-like exposure of Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks surrounded by outcrops of Paleozoic and Cretaceous sedimentary strata. At their widest, the exposed Precambrian rocks extend about 65 miles (105 km) westward from the valley of the Colorado River and beneath a broad, gentle topographic basin drained by the Llano River. The subdued topographic basin is underlain by Precambrian rocks and bordered by a discontinuous rim of flat-topped hills. These hills are the dissected edge of the Edwards Plateau, which consist of overlying Cretaceous sedimentary strata. Within this basin and along its margin are down-faulted blocks and erosional remnants of Paleozoic strata which form prominent hills.

The lithology of a rock unit is a description of its physical characteristics visible at outcrop, in hand or core samples, or with low magnification microscopy. Physical characteristics include colour, texture, grain size, and composition. Lithology may refer to either a detailed description of these characteristics, or a summary of the gross physical character of a rock. Examples of lithologies in the second sense include sandstone, slate, basalt, or limestone.

Arkose or arkosic sandstone is a detrital sedimentary rock, specifically a type of sandstone containing at least 25% feldspar. Arkosic sand is sand that is similarly rich in feldspar, and thus the potential precursor of arkose.

The geology of the Australian Capital Territory includes rocks dating from the Ordovician around 480 million years ago, whilst most rocks are from the Silurian. During the Ordovician period the region—along with most of eastern Australia—was part of the ocean floor. The area contains the Pittman Formation consisting largely of Quartz-rich sandstone, siltstone and shale; the Adaminaby Beds and the Acton Shale.

Mudrocks are a class of fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The varying types of mudrocks include siltstone, claystone, mudstone, slate, and shale. Most of the particles of which the stone is composed are less than 1⁄16 mm and are too small to study readily in the field. At first sight, the rock types appear quite similar; however, there are important differences in composition and nomenclature.

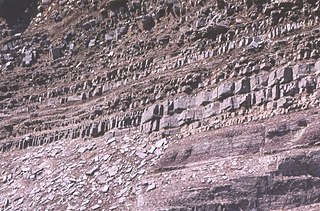

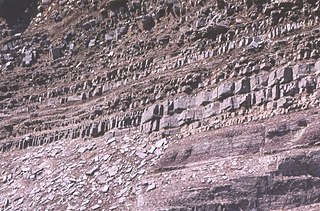

In geology, the term Torridonian is the informal name for the Torridonian Group, a series of Mesoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic arenaceous and argillaceous sedimentary rocks, which occur extensively in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The strata of the Torridonian Group are particularly well exposed in the district of upper Loch Torridon, a circumstance which suggested the name Torridon Sandstone, first applied to these rocks by James Nicol. Stratigraphically, they lie unconformably on gneisses of the Lewisian complex and their outcrop extent is restricted to the Hebridean Terrane.

The Folk classification, in geology, is a technical descriptive classification of sedimentary rocks devised by Robert L. Folk, an influential sedimentary petrologist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Texas.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic to refer to sedimentary rocks and particles in sediment transport, whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

This glossary of geology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to geology, its sub-disciplines, and related fields. For other terms related to the Earth sciences, see Glossary of geography terms.

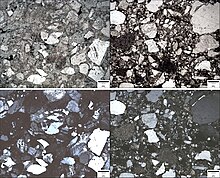

Lithic fragments, or lithics, are pieces of other rocks that have been eroded down to sand size and now are sand grains in a sedimentary rock. They were first described and named by Bill Dickinson in 1970. Lithic fragments can be derived from sedimentary, igneous or metamorphic rocks. A lithic fragment is defined using the Gazzi-Dickinson point-counting method and being in the sand-size fraction. Sand grains in sedimentary rocks that are fragments of larger rocks that are not identified using the Gazzi-Dickinson method are usually called rock fragments instead of lithic fragments. Sandstones rich in lithic fragments are called lithic sandstones.

Cape Town lies at the south-western corner of the continent of Africa. It is bounded to the south and west by the Atlantic Ocean, and to the north and east by various other municipalities in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

The Jordan Formation is a siliciclastic sedimentary rock unit identified in Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. Named for distinctive outcrops in the Minnesota River Valley near the town of Jordan, it extends throughout the Iowa Shelf and eastward over the Wisconsin Arch and Lincoln anticline into the Michigan Basin.

The geology of Bosnia & Herzegovina is the study of rocks, minerals, water, landforms and geologic history in the country. The oldest rocks exposed at or near the surface date to the Paleozoic and the Precambrian geologic history of the region remains poorly understood. Complex assemblages of flysch, ophiolite, mélange and igneous plutons together with thick sedimentary units are a defining characteristic of the Dinaric Alps, also known as the Dinaride Mountains, which dominate much of the country's landscape.