The Visayas, or the Visayan Islands, are one of the three principal geographical divisions of the Philippines, along with Luzon and Mindanao. Located in the central part of the archipelago, it consists of several islands, primarily surrounding the Visayan Sea, although the Visayas are also considered the northeast extremity of the entire Sulu Sea. Its inhabitants are predominantly the Visayan peoples.

Iloilo, officially the Province of Iloilo, is a province in the Philippines located in the Western Visayas region. Its capital and largest city is Iloilo City, the regional center of Western Visayas. Iloilo occupies the southeast portion of the Visayan island of Panay and is bordered by the province of Antique to the west, Capiz to the north, the Jintotolo Channel to the northeast, the Guimaras Strait to the east, and the Iloilo Strait and Panay Gulf to the southwest.

Western Visayas is an administrative region in the Philippines, numerically designated as Region VI. It consists of six provinces and two highly urbanized cities. The regional center is Iloilo City. The region is dominated by the native speakers of four Visayan languages: Hiligaynon, Kinaray-a, Aklanon and Capiznon. The land area of the region is 20,794.18 km2 (8,028.68 sq mi), and with a population of 7,954,723 inhabitants, it is the second most populous region in the Visayas after Central Visayas.

Cebuano is an Austronesian language spoken in the southern Philippines. It is natively, though informally, called by its generic term Bisayâ or Binisayâ and sometimes referred to in English sources as Cebuan. It is spoken by the Visayan ethnolinguistic groups native to the islands of Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, the eastern half of Negros, the western half of Leyte, and the northern coastal areas of Northern Mindanao and the Zamboanga del Norte due to Spanish settlements during 18th century. In modern times, it has also spread to the Davao Region, Cotabato, Camiguin, parts of the Dinagat Islands, and the lowland regions of Caraga, often displacing native languages in those areas.

Visayans or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic family group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. They are composed of numerous distinct ethnic groups, many unrelated to each other. When taken as a single group, they number around 33.5 million. The Visayans, like the Luzon Lowlanders were originally predominantly animist-polytheists and broadly share a maritime culture until they were colonized in the 16th century and a Christian belief system was imposed on them under centuries of colonial rule by Western imperialists. In more inland or otherwise secluded areas, ancient animistic-polytheistic beliefs and traditions either were reinterpreted within a Roman Catholic framework or syncretized with the new religion. Visayans are generally speakers of one or more of the distinct Bisayan languages, the most widely spoken being Cebuano, followed by Hiligaynon (Ilonggo) and Waray-Waray.

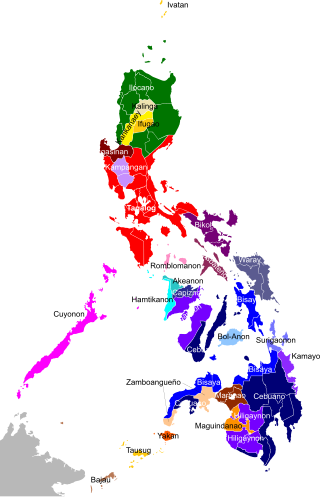

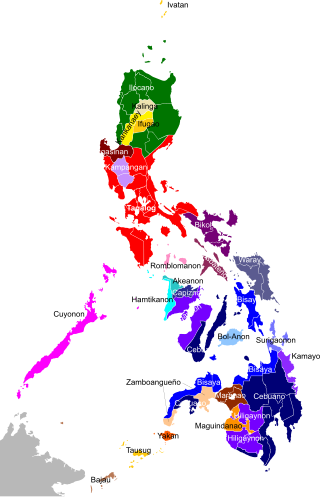

The Bisayan languages or Visayan languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages spoken in the Philippines. They are most closely related to Tagalog and the Bikol languages, all of which are part of the Central Philippine languages. Most Bisayan languages are spoken in the whole Visayas section of the country, but they are also spoken in the southern part of the Bicol Region, islands south of Luzon, such as those that make up Romblon, most of the areas of Mindanao and the province of Sulu located southwest of Mindanao. Some residents of Metro Manila also speak one of the Bisayan languages.

The Central Philippine languages are the most geographically widespread demonstrated group of languages in the Philippines, being spoken in southern Luzon, Visayas, Mindanao, and Sulu. They are also the most populous, including Tagalog, Bikol, and the major Visayan languages Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Kinaray-a, and Tausug, with some forty languages all together.

Masbateño or Minasbate is a member of Central Philippine languages and of the Bisayan subgroup of the Austronesian language family spoken by more than 724,000 people in the province of Masbate and some parts of Sorsogon in the Philippines. Masbatenyo is the name used by the speakers of the language and for themselves, although the term Minásbate is sometimes also used to distinguish the language from the people. It has 350,000 speakers as of 2002, with 50,000 who speak it as their first language. About 250,000 speakers use it as their second language.

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups, many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous people groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro. Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

The Hiligaynon people, often referred to as Ilonggo people or Panayan people, are the second largest subgroup of the larger Visayan ethnic group, whose primary language is Hiligaynon, an Austronesian language of the Visayan branch native to Panay, Guimaras, and Negros. They originated in the province of Iloilo, on the island of Panay, in the region of Western Visayas. Over the years, inter-migrations and intra-migrations have contributed to the diaspora of the Hiligaynon to different parts of the Philippines. Today, the Hiligaynon, apart from the province of Iloilo, also form the majority in the provinces of Guimaras, Negros Occidental, Capiz, South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, and North Cotabato.

The Cebuano people are the largest subgroup of the larger ethnolinguistic group Visayans, who constitute the largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group in the country. They originated in the province of Cebu in the region of Central Visayas, but then later spread out to other places in the Philippines, such as Siquijor, Bohol, Negros Oriental, southwestern Leyte, western Samar, Masbate, and large parts of Mindanao. It may also refer to the ethnic group who speak the same language as their native tongue in different parts of the archipelago. The term Cebuano also refers to the demonym of permanent residents in Cebu island regardless of ethnicity.

Cebuano grammar encompasses the rules that define the Cebuano language, the most widely spoken of all the languages in the Visayan Group of languages, spoken in Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, part of Leyte island, part of Samar island, Negros Oriental, especially in Dumaguete, and the majority of cities and provinces of Mindanao.

Binignit is a Visayan dessert soup from the central Philippines. The dish is traditionally made with glutinous rice cooked in coconut milk with various slices of sabá bananas, taro, ube, and sweet potato, among other ingredients. It is comparable to various dessert guinataán dishes found in other regions such as bilo-bilo. Among the Visayan people, the dish is traditionally served during Good Friday of Holy Week.

The Suludnon, also known as the Panay-Bukidnon, Pan-ayanon, or Tumandok, are a culturally indigenous Visayan group of people who reside in the Capiz-Lambunao mountainous area and the Antique-Iloilo mountain area of Panay in the Visayan islands of the Philippines. They are one of the two only culturally indigenous group of Visayan language-speakers in the Western Visayas, along with the, Halawodnon of Lambunao and Calinog, Iloilo and Iraynon-Bukidnon of Antique. Also, they are part of the wider Visayan ethnolinguistic group, who constitute the largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group.

The Bible has been translated into multiple Philippine languages, including Filipino language, based on the Tagalog, the national language of the Philippines.

The Karay-a language is an Austronesian regional language in the Philippines spoken by the Karay-a people, mainly in Antique.

Waray is an Austronesian language and the fifth-most-spoken native regional language of the Philippines, native to Eastern Visayas. It is the native language of the Waray people and second language of the Abaknon people of Capul, Northern Samar, and some Cebuano-speaking peoples of western and southern parts of Leyte island. It is the third most spoken language among the Bisayan languages, only behind Cebuano and Hiligaynon.

Asín tibuok is a rare Filipino artisanal sea salt from the Boholano people made from filtering seawater through ashes. A related artisanal salt is known as túltul or dúkdok among the Ilonggo people. It is made similarly to asín tibuok but is boiled with gatâ.

Hiligaynon literature consists of both the oral and written works in Hiligaynon, the language of the Hiligaynon people in the Philippine regions of Western Visayas and Soccsksargen.

Ramon Muzones was a writer and lawyer and the posthumous recipient of the National Artist of the Philippines for Literature award in the Philippines in 2018. He wrote in Hiligaynon and popularized Hiligaynon literature.