Chinese is a group of languages that forms the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages. Chinese languages are spoken by the ethnic Chinese majority and many minority ethnic groups in China. About 1.2 billion people speak some form of Chinese as their first language.

Word play or wordplay is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, phonetic mix-ups such as spoonerisms, obscure words and meanings, clever rhetorical excursions, oddly formed sentences, double entendres, and telling character names.

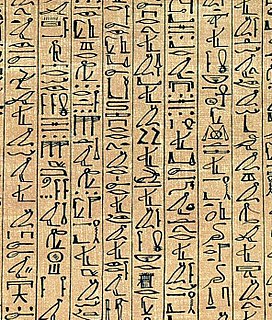

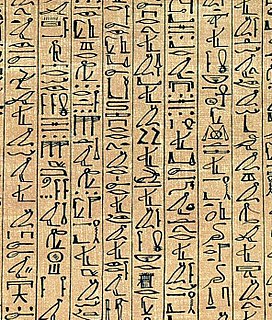

In a written language, a logogram or logograph is a written character that represents a word or phrase. Chinese characters are logograms; some Egyptian hieroglyphs and some graphemes in cuneiform script are also logograms. The use of logograms in writing is called logography, and a writing system that is based on logograms is called a logographic system. In the alphabets and syllabaries, individual written characters represent sounds only, rather than entire concepts. These characters are called phonograms in linguistics. Unlike logograms, phonograms do not have word or phrase meanings singularly until the phonograms are combined with additional phonograms thus creating words and phrases that have meaning. Writing language in this way, is called phonetic writing as well as orthographical writing.

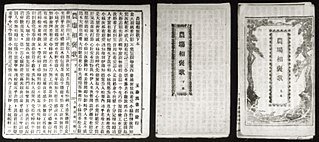

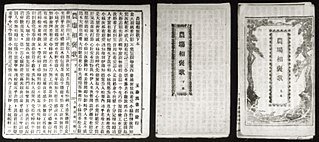

Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese, is the language of the classic literature from the end of the Spring and Autumn period through to the end of the Han dynasty, a written form of Old Chinese. Classical Chinese is a traditional style of written Chinese that evolved from the classical language, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese. Literary Chinese was used for almost all formal writing in China until the early 20th century, and also, during various periods, in Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Among Chinese speakers, Literary Chinese has been largely replaced by written vernacular Chinese, a style of writing that is similar to modern spoken Mandarin Chinese, while speakers of non-Chinese languages have largely abandoned Literary Chinese in favor of local vernaculars.

A homophone is a word that is pronounced the same as another word but differs in meaning. A homophone may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, such as rose (flower) and rose, or differently, such as carat, and carrot, or to, two, and too. The term "homophone" may also apply to units longer or shorter than words, such as phrases, letters, or groups of letters which are pronounced the same as another phrase, letter, or group of letters. Any unit with this property is said to be "homophonous".

The Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den is a passage composed of 92 characters written in Classical Chinese by Chinese-American linguist and poet Yuen Ren Chao (1892–1982), in which every syllable has the sound "shi" when read in modern Mandarin Chinese, with only the tones differing.

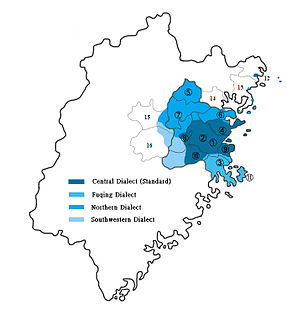

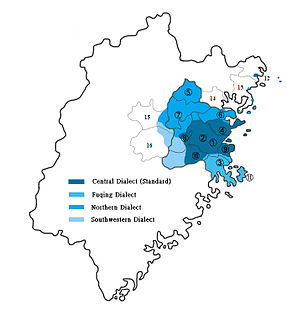

The Fuzhou dialect, also Fuzhounese, Foochow or Hok-chiu, is the prestige variety of the Eastern Min branch of Min Chinese spoken mainly in the Mindong region of eastern Fujian province. Like many other varieties of Chinese, the Fuzhou dialect is dominated by monosyllabic morphemes that carry lexical tones, and has a mainly analytic syntax. While the Eastern Min branch it belongs to is relatively closer to Southern Min or Hokkien than to other Sinitic branches such as Mandarin, Wu Chinese or Hakka, they are still not mutually intelligible.

Nian gao, sometimes translated as year cake or Chinese New Year's cake, is a food prepared from glutinous rice flour and consumed in Chinese cuisine. While it can be eaten all year round, traditionally it is most popular during Chinese New Year. It is considered good luck to eat nian gao during this time, because nian gao is a homonym for "higher year." The Chinese word 粘 (nián), meaning "sticky", is identical in sound to 年, meaning "year", and the word 糕 (gāo), meaning "cake" is identical in sound to 高, meaning "high or tall". As such, eating nian gao has the symbolism of raising oneself taller in each coming year. It is also known as a rice cake. This sticky sweet snack was believed to be an offering to the Kitchen God, with the aim that his mouth will be stuck with the sticky cake, so that he can't badmouth the human family in front of the Jade Emperor. It is also traditionally eaten during the Duanwu Festival.

A reunion dinner is held on New Year's Eve of the Chinese and Vietnamese New Years, during which family members get together to celebrate. It is often considered the most important get-together meal of the entire year.

Erhua ; also called erization, rhotacization of syllable finals, refers to a phonological process that adds r-coloring or the "er" sound to syllables in spoken Mandarin Chinese. Erhuayin is the pronunciation of "er" after rhotacization of syllable finals.

The following faux pas are derived from homonyms in Mandarin and Cantonese. While originating in Greater China, they may also apply to Chinese-speaking people around the world. However, most homonymic pairs listed work only in some varieties of Chinese, and may appear bewildering even to speakers of other varieties of Chinese.

Xiehouyu is a kind of Chinese proverb consisting of two elements: the former segment presents a novel scenario while the latter provides the rationale thereof. One would often only state the first part, expecting the listener to know the second. Compare English "an apple a day " or "speak of the devil ".

A kakekotoba (掛詞) or pivot word is a rhetorical device used in the Japanese poetic form waka. This trope uses the phonetic reading of a grouping of kanji to suggest several interpretations: first on the literal level, then on subsidiary homophonic levels. Thus it is that many waka have pine trees waiting around for something. The presentation of multiple meanings inherent in a single word allows the poet a fuller range of artistic expression with an economical syllable-count. Such brevity is highly valued in Japanese aesthetics, where maximal meaning and reference are sought in a minimal number of syllables. Kakekotoba are generally written in the Japanese phonetic syllabary, hiragana, so that the ambiguous senses of the word are more immediately apparent.

The character Fú meaning "fortune" or "good luck" is represented both as a Chinese ideograph, but also at times pictorially, in one of its homophonous forms. It is often found on a figurine of the male god of the same name, one of the trio of "star gods" Fú, Lù, Shòu.

Chinese New Year is the Chinese festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year on the traditional Chinese calendar. The festival is commonly referred to as the Spring Festival in China as the spring season in the lunisolar calendar traditionally starts with lichun, the first of the twenty-four solar terms which the festival celebrates around the time of. Marking the end of winter and the beginning of the spring season, observances traditionally take place from New Year’s Eve, the evening preceding the first day of the year to the Lantern Festival, held on the 15th day of the year. The first day of Chinese New Year begins on the new moon that appears between 21 January and 20 February. In 2020, the first day of the Chinese New Year was on Saturday, 25 January, which initiated the Year of the Rat.

This article summarizes the phonology of Standard Chinese.

River crab and harmonious/harmonize/harmonization are Internet slang terms created by Chinese netizens in reference to the Internet censorship, or other kinds of censorship in China. In Mandarin Chinese, the word "river crab" (河蟹), which originally means Chinese mitten crab, sounds similar to "harmonious/harmonize/harmonization" in the word "harmonious society" (和谐社会), ex-Chinese leader Hu Jintao's signature ideology.

Singaporean Hokkien is the largest non-Mandarin Chinese dialect spoken in Singapore. As such, it exerts the greatest influence on Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin, resulting in a Hokkien-style Singaporean Mandarin widely spoken in Singapore. The colloquial Hokkien-style Singaporean Mandarin can differ from Mandarin in terms of vocabulary, phonology and grammar.

Hokkien, a Min Nan variety of Chinese spoken in Southeastern China, Taiwan and Southeast Asia, does not have a unitary standardized writing system, in comparison with the well-developed written forms of Cantonese and Vernacular Chinese (Mandarin). In Taiwan, a standard for Written Hokkien has been developed by the Republic of China Ministry of Education including its Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan, but there are a wide variety of different methods of writing in Vernacular Hokkien. Nevertheless, vernacular works written in the Hokkien are still commonly seen in literature, film, performing arts and music.