The civil rights movement was a social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in the country. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century and had its modern roots in the 1940s, although the movement made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans. From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

James Forman was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As the executive secretary of SNCC from 1961 to 1966, Forman played a significant role in the Freedom Rides, the Albany movement, the Birmingham campaign, and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

Diane Judith Nash is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Big Six—Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young—were the leaders of six prominent civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

The Nashville sit-ins, which lasted from February 13 to May 10, 1960, were part of a protest to end racial segregation at lunch counters in downtown Nashville, Tennessee. The sit-in campaign, coordinated by the Nashville Student Movement and the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, was notable for its early success and its emphasis on disciplined nonviolence. It was part of a broader sit-in movement that spread across the southern United States in the wake of the Greensboro sit-ins in North Carolina.

James Luther Bevel was an American minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct Action and Nonviolent Education, Bevel initiated, strategized, and developed SCLC's three major successes of the era: the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade, the 1965 Selma voting rights movement, and the 1966 Chicago open housing movement. He suggested that SCLC call for and join a March on Washington in 1963. Bevel strategized the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, which contributed to Congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Cordy Tindell Vivian was an American minister, author, and close friend and lieutenant of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement. Vivian resided in Atlanta, Georgia, and founded the C. T. Vivian Leadership Institute, Inc. He was a member of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

The Freedom Singers originated as a quartet formed in 1962 at Albany State College in Albany, Georgia. After folk singer Pete Seeger witnessed the power of their congregational-style of singing, which fused black Baptist a cappella church singing with popular music at the time, as well as protest songs and chants. Churches were considered to be safe spaces, acting as a shelter from the racism of the outside world. As a result, churches paved the way for the creation of the freedom song. After witnessing the influence of freedom songs, Seeger suggested The Freedom Singers as a touring group to the SNCC executive secretary James Forman as a way to fuel future campaigns. Intrinsically connected, their performances drew aid and support to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the emerging civil rights movement. As a result, communal song became essential to empowering and educating audiences about civil rights issues and a powerful social weapon of influence in the fight against Jim Crow segregation. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Their most notable song “We Shall Not Be Moved” translated from the original Freedom Singers to the second generation of Freedom Singers, and finally to the Freedom Voices, made up of field secretaries from SNCC. "We Shall Not Be Moved" is considered by many to be the "face" of the Civil Rights movement. Rutha Mae Harris, a former freedom singer, speculated that without the music force of broad communal singing, the civil rights movement may not have resonated beyond of the struggles of the Jim Crow South. Since the Freedom Singers were so successful, a second group was created called the Freedom Voices.

Bernard Lafayette, Jr. is an American civil rights activist and organizer, who was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. He played a leading role in early organizing of the Selma Voting Rights Movement; was a member of the Nashville Student Movement; and worked closely throughout the 1960s movements with groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the American Friends Service Committee.

Prathia Laura Ann Hall Wynn was an American leader and activist in the Civil Rights Movement, a womanist theologian, and ethicist. She was the key inspiration for Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

Bennett Harvie Branscomb was an American theologian and academic administrator. He served as the fourth chancellor of Vanderbilt University, a private university in Nashville, Tennessee, from 1946 to 1963. Prior to his appointment at Vanderbilt, he was the director of the Duke University Libraries and dean of the Duke Divinity School. Additionally, he served as a professor of Christian theology at Southern Methodist University. He was the author of several books about New Testament theology.

The Nashville Student Movement was an organization that challenged racial segregation in Nashville, Tennessee, during the Civil Rights Movement. It was created during workshops in nonviolence taught by James Lawson. The students from this organization initiated the Nashville sit-ins in 1960. They were regarded as the most disciplined and effective of the student movement participants during 1960. The Nashville Student Movement was key in establishing leadership in the Freedom Riders.

Charles "Chuck" McDew was an American lifelong activist for racial equality and a former activist of the Civil Rights Movement. After attending South Carolina State University, he became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1960 to 1963. His involvement in the movement earned McDew the title, "black by birth, a Jew by choice and a revolutionary by necessity" stated by fellow SNCC activist Bob Moses.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

Mary Salynn (Selyn) McCollum was the only white female Freedom Rider during the leg from Nashville, Tennessee to Birmingham, Alabama on May 17, 1961.

The Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) was a local organization in Dallas County, Alabama, which contains the city of Selma, that sought to register black voters during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Carolanne Marie "Candie" Carawan (née Anderson) is an American civil rights activist, singer and author known for popularizing the protest song "We Shall Overcome" to the American Civil Rights Movement with her husband Guy Carawan in the 1960s.

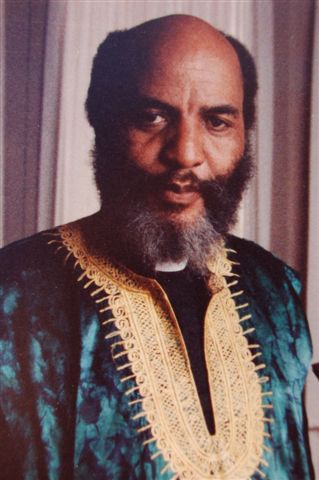

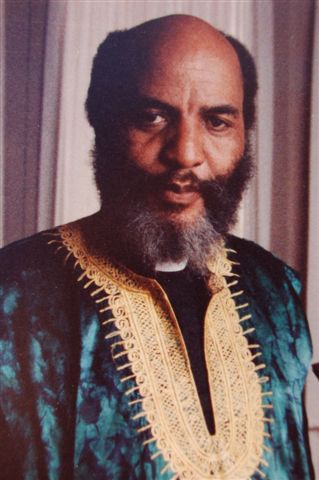

Rodney Norman Powell. is a former civil rights leader in the Nashville Student Movement and an activist for LGBTQ rights.