Related Research Articles

Alexander of Aphrodisias was a Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek commentators on the writings of Aristotle. He was a native of Aphrodisias in Caria and lived and taught in Athens at the beginning of the 3rd century, where he held a position as head of the Peripatetic school. He wrote many commentaries on the works of Aristotle, extant are those on the Prior Analytics, Topics, Meteorology, Sense and Sensibilia, and Metaphysics. Several original treatises also survive, and include a work On Fate, in which he argues against the Stoic doctrine of necessity; and one On the Soul. His commentaries on Aristotle were considered so useful that he was styled, by way of pre-eminence, "the commentator".

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

The history of logic deals with the study of the development of the science of valid inference (logic). Formal logics developed in ancient times in India, China, and Greece. Greek methods, particularly Aristotelian logic as found in the Organon, found wide application and acceptance in Western science and mathematics for millennia. The Stoics, especially Chrysippus, began the development of predicate logic.

Jacobus de Voragine was an Italian chronicler and archbishop of Genoa. He was the author, or more accurately the compiler, of the Golden Legend, a collection of the legendary lives of the greater saints of the medieval church that was one of the most popular religious works of the Middle Ages.

Aristotelianism is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the social sciences under a system of natural law. It answers why-questions by a scheme of four causes, including purpose or teleology, and emphasizes virtue ethics. Aristotle and his school wrote tractates on physics, biology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics, and government. Any school of thought that takes one of Aristotle's distinctive positions as its starting point can be considered "Aristotelian" in the widest sense. This means that different Aristotelian theories may not have much in common as far as their actual content is concerned besides their shared reference to Aristotle.

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, the Peripatetics. It was revived after the third century CE by Porphyry's Isagoge.

The Prior Analytics is a work by Aristotle on reasoning, known as syllogistic, composed around 350 BCE. Being one of the six extant Aristotelian writings on logic and scientific method, it is part of what later Peripatetics called the Organon.

The Organon is the standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logical analysis and dialectic. The name Organon was given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics, who maintained against the Stoics that Logic was "an instrument" of Philosophy.

Albert of Saxony was a German philosopher and mathematician known for his contributions to logic and physics. He was bishop of Halberstadt from 1366 until his death.

The Posterior Analytics is a text from Aristotle's Organon that deals with demonstration, definition, and scientific knowledge. The demonstration is distinguished as a syllogism productive of scientific knowledge, while the definition marked as the statement of a thing's nature, ... a statement of the meaning of the name, or of an equivalent nominal formula.

GiacomoZabarella was an Italian Aristotelian philosopher and logician.

The history of scientific method considers changes in the methodology of scientific inquiry, as distinct from the history of science itself. The development of rules for scientific reasoning has not been straightforward; scientific method has been the subject of intense and recurring debate throughout the history of science, and eminent natural philosophers and scientists have argued for the primacy of one or another approach to establishing scientific knowledge.

Iacobus de Ispania was a music theorist active in the southern Low Countries who compiled The Mirror of Music during the second quarter of the 14th century. Before the discovery of his full name, scholars designated him Jacques de Liège.

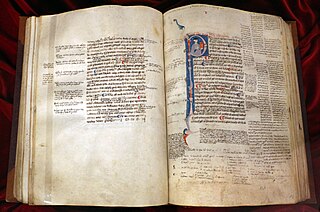

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, which recently had come under Christian rule following their reconquest in the late 11th century. These areas had been under Muslim rule for a considerable time, and still had substantial Arabic-speaking populations to support their search. The combination of this accumulated knowledge and the substantial numbers of Arabic-speaking scholars there made these areas intellectually attractive, as well as culturally and politically accessible to Latin scholars. A typical story is that of Gerard of Cremona, who is said to have made his way to Toledo, well after its reconquest by Christians in 1085, because he:

arrived at a knowledge of each part of [philosophy] according to the study of the Latins, nevertheless, because of his love for the Almagest, which he did not find at all amongst the Latins, he made his way to Toledo, where seeing an abundance of books in Arabic on every subject, and pitying the poverty he had experienced among the Latins concerning these subjects, out of his desire to translate he thoroughly learnt the Arabic language.

Giacomo Filippo Foresti da Bergamo (1434–1520) was an Augustinian friar, known as the author of several significant early printed works. He was a chronicler and Biblical scholar.

In the history of logic, the term logica nova refers to a subdivision of the logical tradition of Western Europe, as it existed around the middle of the twelfth century. The Logica vetus referred to works of Aristotle that had long been known and studied in the Latin West, whereas the Logica nova referred to forms of logic derived from Aristotle's works which had been unavailable until they were translated by James of Venice in the 12th century. Study of the Logica nova was part of the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Bryson of Heraclea was an ancient Greek mathematician and sophist who studied the solving the problems of squaring the circle and calculating pi.

The transmission of the Greek Classics to Latin Western Europe during the Middle Ages was a key factor in the development of intellectual life in Western Europe. Interest in Greek texts and their availability was scarce in the Latin West during the Early Middle Ages, but as traffic to the East increased, so did Western scholarship.

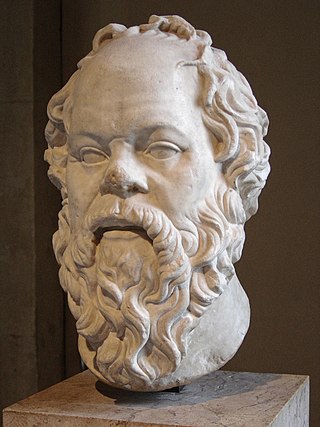

Commentaries on Aristotle refers to the great mass of literature produced, especially in the ancient and medieval world, to explain and clarify the works of Aristotle. The pupils of Aristotle were the first to comment on his writings, a tradition which was continued by the Peripatetic school throughout the Hellenistic period and the Roman era. The Neoplatonists of the Late Roman Empire wrote many commentaries on Aristotle, attempting to incorporate him into their philosophy. Although Ancient Greek commentaries are considered the most useful, commentaries continued to be written by the Christian scholars of the Byzantine Empire and by the many Islamic philosophers and Western scholastics who had inherited his texts.

James of Douai was a French philosopher who taught at the University of Paris.

References

- L. Minio-Paluello, "Iacobus Veneticus Grecus: Canonist and Translator of Aristotle." Traditio 8 (1952), 265–304

- Sten Ebbesen (1977). "Jacobus Veneticus on the Posterior Analytics and Some Early Thirteenth-century Oxford Masters on the Elenchi." Cahiers de l'Institut du moyen âge grec et Latin 2, 1-9.