Acoustic theory is a scientific field that relates to the description of sound waves. It derives from fluid dynamics. See acoustics for the engineering approach.

In mathematics and physics, Laplace's equation is a second-order partial differential equation named after Pierre-Simon Laplace, who first studied its properties. This is often written as

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

In fluid dynamics, potential flow is the ideal flow pattern of an inviscid fluid. Potential flows are described and determined by mathematical methods.

The vorticity equation of fluid dynamics describes the evolution of the vorticity ω of a particle of a fluid as it moves with its flow; that is, the local rotation of the fluid. The governing equation is:

In fluid dynamics, the Euler equations are a set of quasilinear partial differential equations governing adiabatic and inviscid flow. They are named after Leonhard Euler. In particular, they correspond to the Navier–Stokes equations with zero viscosity and zero thermal conductivity.

In vector calculus, a conservative vector field is a vector field that is the gradient of some function. A conservative vector field has the property that its line integral is path independent; the choice of path between two points does not change the value of the line integral. Path independence of the line integral is equivalent to the vector field under the line integral being conservative. A conservative vector field is also irrotational; in three dimensions, this means that it has vanishing curl. An irrotational vector field is necessarily conservative provided that the domain is simply connected.

In fluid mechanics, or more generally continuum mechanics, incompressible flow refers to a flow in which the material density is constant within a fluid parcel—an infinitesimal volume that moves with the flow velocity. An equivalent statement that implies incompressibility is that the divergence of the flow velocity is zero.

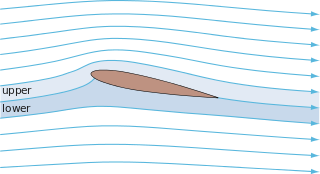

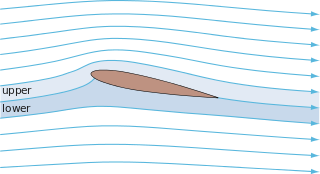

In fluid dynamics, d'Alembert's paradox is a contradiction reached in 1752 by French mathematician Jean le Rond d'Alembert. D'Alembert proved that – for incompressible and inviscid potential flow – the drag force is zero on a body moving with constant velocity relative to the fluid. Zero drag is in direct contradiction to the observation of substantial drag on bodies moving relative to fluids, such as air and water; especially at high velocities corresponding with high Reynolds numbers. It is a particular example of the reversibility paradox.

In fluid mechanics, the Taylor–Proudman theorem states that when a solid body is moved slowly within a fluid that is steadily rotated with a high angular velocity , the fluid velocity will be uniform along any line parallel to the axis of rotation. must be large compared to the movement of the solid body in order to make the Coriolis force large compared to the acceleration terms.

Stokes flow, also named creeping flow or creeping motion, is a type of fluid flow where advective inertial forces are small compared with viscous forces. The Reynolds number is low, i.e. . This is a typical situation in flows where the fluid velocities are very slow, the viscosities are very large, or the length-scales of the flow are very small. Creeping flow was first studied to understand lubrication. In nature, this type of flow occurs in the swimming of microorganisms and sperm. In technology, it occurs in paint, MEMS devices, and in the flow of viscous polymers generally.

In fluid mechanics, potential vorticity (PV) is a quantity which is proportional to the dot product of vorticity and stratification. This quantity, following a parcel of air or water, can only be changed by diabatic or frictional processes. It is a useful concept for understanding the generation of vorticity in cyclogenesis, especially along the polar front, and in analyzing flow in the ocean.

The Navier–Stokes existence and smoothness problem concerns the mathematical properties of solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations, a system of partial differential equations that describe the motion of a fluid in space. Solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations are used in many practical applications. However, theoretical understanding of the solutions to these equations is incomplete. In particular, solutions of the Navier–Stokes equations often include turbulence, which remains one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics, despite its immense importance in science and engineering.

In fluid mechanics, Kelvin's circulation theorem states:

In a barotropic, ideal fluid with conservative body forces, the circulation around a closed curve moving with the fluid remains constant with time.

In plasma physics, the Hasegawa–Mima equation, named after Akira Hasegawa and Kunioki Mima, is an equation that describes a certain regime of plasma, where the time scales are very fast, and the distance scale in the direction of the magnetic field is long. In particular the equation is useful for describing turbulence in some tokamaks. The equation was introduced in Hasegawa and Mima's paper submitted in 1977 to Physics of Fluids, where they compared it to the results of the ATC tokamak.

The intent of this article is to highlight the important points of the derivation of the Navier–Stokes equations as well as its application and formulation for different families of fluids.

The Cauchy momentum equation is a vector partial differential equation put forth by Cauchy that describes the non-relativistic momentum transport in any continuum.

In fluid dynamics, aerodynamic potential flow codes or panel codes are used to determine the fluid velocity, and subsequently the pressure distribution, on an object. This may be a simple two-dimensional object, such as a circle or wing, or it may be a three-dimensional vehicle.

In fluid dynamics, Luke's variational principle is a Lagrangian variational description of the motion of surface waves on a fluid with a free surface, under the action of gravity. This principle is named after J.C. Luke, who published it in 1967. This variational principle is for incompressible and inviscid potential flows, and is used to derive approximate wave models like the mild-slope equation, or using the averaged Lagrangian approach for wave propagation in inhomogeneous media.

In fluid dynamics, The projection method is an effective means of numerically solving time-dependent incompressible fluid-flow problems. It was originally introduced by Alexandre Chorin in 1967 as an efficient means of solving the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. The key advantage of the projection method is that the computations of the velocity and the pressure fields are decoupled.