Related Research Articles

Underground, is a 1995 epic satirical black comedy war film directed by Emir Kusturica, with a screenplay co-written with Dušan Kovačević. It is also known by the subtitle Once Upon a Time There Was One Country, the title of the five-hour miniseries shown on Serbian RTS television.

The Order of the People's Hero or the Order of the National Hero, was a Yugoslav gallantry medal, the second highest military award, and third overall Yugoslav decoration. It was awarded to individuals, military units, political and other organisations who distinguished themselves by extraordinary heroic deeds during war and in peacetime. The recipients were thereafter known as People's Heroes of Yugoslavia or National Heroes of Yugoslavia. The vast majority was awarded to partisans for actions during the Second World War. A total of 1,322 awards were awarded in Yugoslavia, and 19 were awarded to foreigners.

Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu is the second studio album from influential Yugoslav rock band Bijelo Dugme, released in 1975.

Karađorđeva šnicla is a breaded cutlet dish named after the Serbian revolutionary Karađorđe. The dish consists of a rolled veal, pork, or chicken steak, stuffed with kaymak, which is then breaded and fried. It is served with tartar sauce and a slice of lemon on the side, and sometimes french fries or steamed vegetables. Created by Josip Broz Tito's chef Mića Stojanović in 1956 or 1957 as an improvisation of Chicken Kyiv, it has become a regular staple in Serbian cuisine. Stojanović unsuccessfully tried to patent his original recipe, which has since been adapted to several variations.

Lazar "Laza" Ristovski is a Serbian former actor, director, producer and writer. He has appeared on stage about 4,000 times, and starred in over 90 films and 30 TV series, mostly in lead roles. He briefly served as a member of the National Assembly from 1 August 2022 until his resignation on 9 August 2022.

Matija Vuković was a Serbian sculptor.

Disciplin A Kitschme, originally known as Disciplina Kičme, was a Serbian and Yugoslav and, for a period of time, British rock band, formed in Belgrade in 1981. The band was noted for their unique and energetic sound, with bass guitar as the primary instrument and drawing inspiration from punk rock, funk, blues, jazz fusion, Motown, rap, the works of Jimi Hendrix, Yugoslav 1970s progressive and hard rock bands, and in the later phases of their career from jungle and drum and bass.

Oliver Mandić is a Serbian and former Yugoslav rock musician, composer, and producer.

The Cinema of Serbia refers to the film industry and films made in Serbia or by Serbian filmmakers.

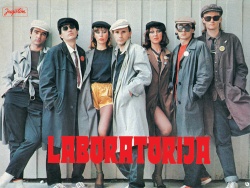

Laboratorija Zvuka, credited as Laboratorija (Laboratory) only on some of their releases, was a Serbian and Yugoslav rock band formed in Novi Sad in 1977. Laboratorija Zvuka were a prominent act of the Yugoslav rock scene, noted for their eccentric style, erotic lyrics, unusual line ups and bizarre circus-inspired stage performances.

![<i>Tito and Me</i> 1992 [[Federal Republic of Yugoslavia|FR Yugoslavia]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/c/ca/Tito_i_ja.jpg)

Tito and Me is a 1992 comedy film by Serbian director Goran Marković.

Mladen Stojanović was a Bosnian Serb and Yugoslav physician who led a detachment of Partisans on and around Mount Kozara in northwestern Bosnia during World War II in Yugoslavia. He was posthumously bestowed the Order of the People's Hero.

Zdravko Velimirović was a Yugoslavian film director and screenwriter, University Professor, a member of the Academy of Arts and Sciences. He also directed over fifty documentaries and short films and eight feature films between 1954 and 2005, twenty radio dramas, five theatre plays and had varied art photography exhibitions.

S Vremena Na Vreme was a Serbian and Yugoslav rock band formed in Belgrade in 1972. S Vremena Na Vreme were one of the pioneers of the Yugoslav 1970s acoustic rock scene, and one of the pioneers in incorporating elements of the traditional music of the Balkans into rock music. The group was one of the most prominent acts of the 1970s Yugoslav rock scene.

Yugoslav Black Wave is a blanket term for a Yugoslav film and broader cultural movement starting from the early 1960s and ending in the early 1970s. Notable directors include Dušan Makavejev, Žika Pavlović, Aleksandar Petrović, Želimir Žilnik, Mika Antić, Lordan Zafranović, Mića Popović, Đorđe Kadijević and Marko Babac. Black Wave films are known for their non-traditional approach to filmmaking, dark humor and their critical examination of socialist Yugoslav society.

The Batajnica mass graves are mass graves that were found in 2001 near Batajnica, a suburb of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. The graves contained the bodies of 744 Kosovar Albanians civilians that were killed during the Kosovo War. The mass graves were found on the training grounds of the Yugoslav Special Anti-Terrorist Unit (SAJ). Dead bodies were brought to the site by trucks from Kosovo; most were incinerated before burial. After the war, SAJ restricted investigators' access to the firing range, and continued live-firing exercises whilst forensic teams tried to investigate the massacre.

The Battle of Pljevlja, was a World War II attack in the Italian governorate of Montenegro by Yugoslav Partisans under the command of General Arso Jovanović and Colonel Bajo Sekulić, who led 4,000 Montenegrin Partisans against the Italian occupiers in the town of Pljevlja.

![<i>When I Am Dead and Gone</i> 1967 [[Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia|Yugoslavia]] film](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/6/63/When_I_Am_Dead_and_Gone_Poster.jpg)

When I Am Dead and Gone is a 1967 Yugoslav film directed by Živojin Pavlović and written by Ljubiša Kozomara and Gordan Mihić. It stars famous Serbian actors Dragan Nikolić and Ružica Sokić.

Student protests were held in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, as the first mass protest in Yugoslavia after World War II. Protests then also erupted in some of the capitals of the other Yugoslav republics — Sarajevo, Zagreb and Ljubljana — but they were smaller and shorter-lasting than those in Belgrade.

Egypt–Yugoslavia relations were historical foreign relations between Egypt and now break-up Yugoslavia. Both countries were founding members and prominent participants of the Non-Aligned Movement. While initially marginal, relations between the two Mediterranean countries developed significantly in the aftermath of the Soviet-Yugoslav split of 1948 and the Egyptian revolution of 1952. Belgrade hosted the Non-Aligned movement's first conference for which preparatory meeting took place in Cairo, while Cairo hosted the second conference. While critical of certain aspects of the Camp David Accords Yugoslavia remained major advocate for Egyptian realist approach within the movement, and strongly opposed harsh criticism of Cairo or proposals which questioned country's place within the movement.

References

- ↑ "Republika – Glasilo gradjanskog samooslobadjanja". republika.co.rs. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ↑ "Vreme – Intervju – Lazar Stojanović, reditelj: NATO nema alternativu". vreme.com. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ↑ Levi, Pavle (2007). Disintegration in frames: Aesthetics and ideology in the Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav cinema. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 13–56.

- ↑ "Short clips from the film can be watched here: Courage- Collecting collections".

- ↑ DeCuir, Greg (2011). Yugoslav black wave: Polemical Cinema from 1963–1973 in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Belgrade: Film Center Serbia. pp. 227–250.

- ↑ "Museum of Modern Art". moma.org.

- ↑ "More about the two trials can be found here: Courage- Collecting collections".

- ↑ Kanzleiter, Boris (2011). "Rote Universität.": Studentenbewegung und Linksopposition in Belgrad 1964–1975. Hamburg: VSA.

- ↑ Solomun, Zoran (2012). Plastic Jesus. Tito und die jugoslawischen Achtungsechziger (PDF). Deutschlandfunk.

- ↑ "Lazar Stojanović has Passed Away – Fond za humanitarno pravo/Humanitarian Law Center/Fondi për të Drejtën Humanitare | Fond za humanitarno pravo/Humanitarian Law Center/Fondi për të Drejtën Humanitare". www.hlc-rdc.org (in German). Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ↑ Pantić, A. (2015). Lazar Stojanović: Svako Sam Odlučuje Kad će Da Bude Hrabar. 24 sata.