Chios is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the tenth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic gum and its nickname is "the Mastic Island". Tourist attractions include its medieval villages and the 11th-century monastery of Nea Moni, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted by the British Empire, Kingdom of France, and the Russian Empire, while the Ottomans were aided by their North African vassals, particularly the eyalet of Egypt. The war led to the formation of modern Greece, which would be expanded to its modern size in later years. The revolution is celebrated by Greeks around the world as independence day on 25 March every year.

The Orlov revolt was a Greek uprising in the Peloponnese and later also in Crete that broke out in February 1770, following the arrival of Russian Admiral Alexey Orlov, commander of the Imperial Russian Navy during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), at the Mani Peninsula. The revolt, a major precursor to the Greek War of Independence, was part of Catherine the Great's so-called "Greek Plan" and was eventually suppressed by the Ottomans.

The vast majority of the territory of present-day Greece was at some point incorporated within the Ottoman Empire. The period of Ottoman rule in Greece, lasting from the mid-15th century to the successful Greek War of Independence that broke out in 1821 and the First Hellenic Republic was proclaimed in 1822, is known in Greek as Tourkokratia. Some regions, however, like the Ionian islands and various temporary Venetian possessions of the Stato da Mar were not incorporated in the Ottoman Empire. The Mani Peninsula in Peloponnese was not fully integrated into the Ottoman Empire, but was under Ottoman suzerainty.

The Battle of Vromopigada was fought between the Ottoman Turks and the Maniots of Mani in 1770. The location of the battle was in a plain between the two towns of Skoutari and Parasyros. The battle ended in a Greek victory.

Greek Muslims, also known as Muslim Rums, are Muslims of Greek ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam dates to the period of Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans. They consist primarily of Ottoman-era converts to Islam from Greek Macedonia, Crete, and northeastern Anatolia.

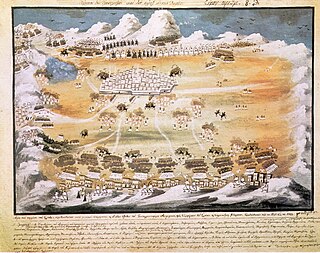

The Chios massacre was a catastrophe that resulted in the death, enslavement, and flight of about four-fifths of the total population of Greeks on the island of Chios by Ottoman troops, during the Greek War of Independence in 1822. It is estimated that up to 100,000 people were killed or enslaved during the massacre, while up to 20,000 escaped as refugees. Greeks from neighboring islands had arrived on Chios and encouraged the Chiotes to join their revolt. In response, Ottoman troops landed on the island and killed thousands. The massacre of Christians provoked international outrage across the Western world, and led to increasing support for the Greek cause worldwide.

Ibrahim Edhem Pasha (1819–1893) was an Ottoman statesman, who held the office of Grand Vizier in the beginning of Abdul Hamid II's reign between 5 February 1877 and 11 January 1878. He resigned from that post after the Ottoman chances on winning the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) had decreased. He furthermore served numerous administrative positions in the Ottoman Empire including minister of foreign affairs in 1856, then ambassador to Berlin in 1876, and to Vienna from 1879 to 1882. He also served as a military engineer and as Minister of Interior from 1883 to 1885. In 1876–1877, he represented the Ottoman Government at the Constantinople Conference.

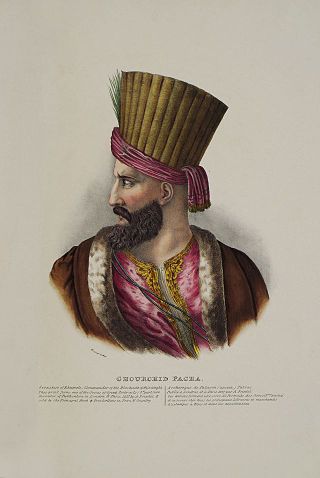

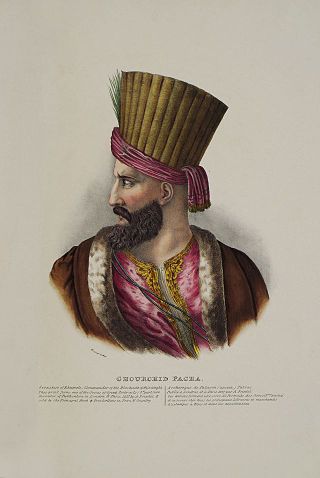

Hurshid Ahmed Pasha was an Ottoman-Georgian general, and Grand Vizier during the early 19th century.

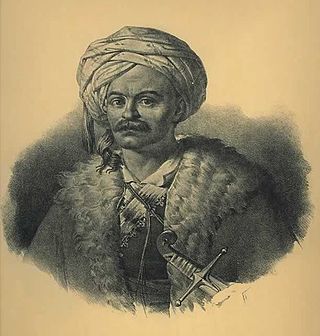

Major-General Thomas Gordon was a British army officer and historian. He is remembered for his role in the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s and 1830s and his History of the war published in 1832.

This is a timeline of modern Greek history.

The Destruction of Psara was the killing of thousands of Greeks on the island of Psara by Ottoman troops during the Greek War of Independence in 1824.

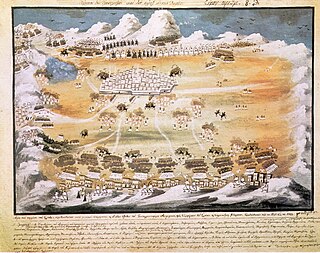

The siege of Tripolitsa or fall of Tripolitsa, also known as the Tripolitsa massacre, was an early victory of the revolutionary Greek forces in the summer of 1821 during the Greek War of Independence, which had begun earlier that year, against the Ottoman Empire. Tripolitsa was an important target, because it was the administrative center of the Ottomans in the Peloponnese.

The Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War was fought between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire between 1714 and 1718. It was the last conflict between the two powers, and ended with an Ottoman victory and the loss of Venice's major possession in the Greek peninsula, the Peloponnese (Morea). Venice was saved from a greater defeat by the intervention of Austria in 1716. The Austrian victories led to the signing of the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718, which ended the war.

The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the subsequent fall of the successor states of the Eastern Roman Empire marked the end of Byzantine sovereignty. Since then, the Ottoman Empire ruled the Balkans and Anatolia, although there were some exceptions: the Ionian Islands were under Venetian rule, and Ottoman authority was challenged in mountainous areas, such as Agrafa, Sfakia, Souli, Himara and the Mani Peninsula. Orthodox Christians were granted some political rights under Ottoman rule, but they were considered inferior subjects. The majority of Greeks were called rayas by the Turks, a name that referred to the large mass of subjects in the Ottoman ruling class. Meanwhile, Greek intellectuals and humanists who had migrated west before or during the Ottoman invasions began to compose orations and treatises calling for the liberation of their homeland. In 1463, Demetrius Chalcondyles called on Venice and “all of the Latins” to aid the Greeks against the Ottomans, he composed orations and treatises calling for the liberation of Greece from what he called “the abominable, monstrous, and impious barbarian Turks.” In the 17th century, Greek scholar Leonardos Philaras spent much of his career in persuading Western European intellectuals to support Greek independence. However, Greece was to remain under Ottoman rule for several more centuries. In the 18th and 19th century, as revolutionary nationalism grew across Europe—including the Balkans —the Ottoman Empire's power declined and Greek nationalism began to assert itself, with the Greek cause beginning to draw support not only from the large Greek merchant diaspora in both Western Europe and Russia but also from Western European Philhellenes. This Greek movement for independence, was not only the first movement of national character in Eastern Europe, but also the first one in a non-Christian environment, like the Ottoman Empire.

The island of Crete was declared an Ottoman province (eyalet) in 1646, after the Ottomans managed to conquer the western part of the island as part of the Cretan War, but the Venetians maintained their hold on the capital Candia, until 1669, when Francesco Morosini surrendered the keys of the town. The offshore island fortresses of Souda, Grambousa, and Spinalonga would remain under Venetian rule until 1715, when they were also captured by the Ottomans.

The Constantinople massacre of 1821 was orchestrated by the authorities of the Ottoman Empire against the Greek community of Constantinople in retaliation for the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830). As soon as the first news of the Greek uprising reached the Ottoman capital, there occurred mass executions, pogrom-type attacks, destruction of churches, and looting of the properties of the city's Greek population. The events culminated with the hanging of the Ecumenical Patriarch, Gregory V and the beheading of the Grand Dragoman, Konstantinos Mourouzis.

The Chios expedition was an unsuccessful attempt of the regular Greek army

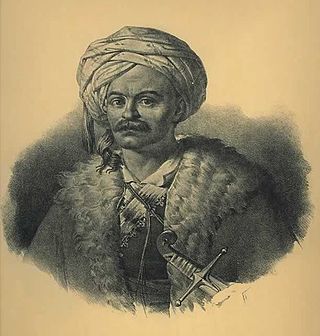

Nasuhzade Ali Pasha, commonly known as Kara Ali Pasha, was an Ottoman-Albanian admiral during the early stages of the Greek War of Independence. In 1821, as second-in-command of the Ottoman navy, he succeeded in resupplying the isolated Ottoman fortresses in the Peloponnese, while his subordinate Ismael Gibraltar destroyed Galaxeidi. Promoted to Kapudan Pasha, and led the suppression of the revolt in Chios and the ensuing Chios massacre in April 1822. He was killed when a fireship captained by Konstantinos Kanaris blew up his flagship in Chios harbour on the night of 18/19 June 1822.

Greece and the Ottoman Empire had a history of conflict. They developed formal relations in 1830 when Greece was recognised as an independent state by the Ottoman Empire following the Greek War of Independence.