The Baltic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively or as a second language by a population of about 6.5–7.0 million people mainly in areas extending east and southeast of the Baltic Sea in Europe. Together with the Slavic languages, they form the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European family.

Finno-Ugric is a traditional grouping of all languages in the Uralic language family except the Samoyedic languages. Its formerly commonly accepted status as a subfamily of Uralic is based on criteria formulated in the 19th century and is criticized by some contemporary linguists such as Tapani Salminen and Ante Aikio. The three most-spoken Uralic languages, Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian, are all included in Finno-Ugric.

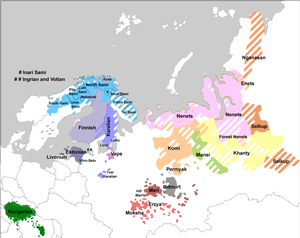

The Uralic languages form a language family of 42 languages spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers above 100,000 are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi spoken in the European parts of the Russian Federation. Still smaller minority languages are Sámi languages of the northern Fennoscandia; other members of the Finnic languages, ranging from Livonian in northern Latvia to Karelian in northwesternmost Russia; and the Samoyedic languages, Mansi and Khanty spoken in Western Siberia.

Finns or Finnish people are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Bjarmaland was a territory mentioned in Norse sagas since the Viking Age and in geographical accounts until the 16th century. The term is usually seen to have referred to the southern shores of the White Sea and the basin of the Northern Dvina River as well as, presumably, some of the surrounding areas. Today, those territories comprise a part of the Arkhangelsk Oblast of Russia, as well as the Kola Peninsula.

Chud or Chude is a term historically applied in the early East Slavic annals to several Baltic Finnic peoples in the area of what is now Estonia, Karelia and Northwestern Russia. It has also been used to refer to other Finno-Ugric peoples.

Finno-Volgaic or Fenno-Volgaic is a hypothetical branch of the Uralic languages that tried to group the Finnic languages, Sami languages, Mordvinic languages and the Mari language. It was hypothesized to have branched from the Finno-Permic languages about 2000 BC.

The Finno-Samic languages are a hypothetical subgroup of the Uralic family, and are made up of 22 languages classified into either the Sami languages, which are spoken by the Sami people who inhabit the Sápmi region of northern Fennoscandia, or Finnic languages, which include the major languages Finnish and Estonian. The grouping is not universally recognized as valid.

Proto-Uralic is the unattested reconstructed language ancestral to the modern Uralic language family. The hypothetical language is thought to have been originally spoken in a small area in about 7000–2000 BCE, and expanded to give differentiated Proto-Languages. Some newer research has pushed the "Proto-Uralic homeland" east of the Ural Mountains into Western Siberia.

The Finnic or Baltic Finnic languages constitute a branch of the Uralic language family spoken around the Baltic Sea by the Baltic Finnic peoples. There are around 7 million speakers, who live mainly in Finland and Estonia.

The Finno-Permic or Finno-Permian languages, sometimes just Finnic or Fennic languages, are a proposed subdivision of the Uralic languages which comprise the Balto-Finnic languages, Sámi languages, Mordvinic languages, Mari language, Permic languages and likely a number of extinct languages. In the traditional taxonomy of the Uralic languages, Finno-Permic is estimated to have split from Finno-Ugric around 3000–2500 BC, and branched into Permic languages and Finno-Volgaic languages around 2000 BC. Nowadays the validity of the group as a taxonomical entity is being questioned, and the interrelationships of its five branches are debated with little consensus.

The Meryans were an ancient Finnic people that lived in the Upper Volga region. The Primary Chronicle places them around the Nero and Pleshcheyevo lakes. They were assimilated to Russians around the 13th century.

The Volga Finns are a historical group of peoples living in the vicinity of the Volga, who speak Uralic languages. Their modern representatives are the Mari people, the Erzya and the Moksha Mordvins, as well as speakers of the extinct Merya, Muromian and Meshchera languages. The Permians are sometimes also grouped as Volga Finns.

The Baltic Finnic peoples, often simply referred to as the Finnic peoples, are the peoples inhabiting the Baltic Sea region in Northern and Eastern Europe who speak Finnic languages. They include the Finns, Estonians, Karelians, Veps, Izhorians, Votes, and Livonians. In some cases the Kvens, Ingrians, Tornedalians and speakers of Meänkieli are considered separate from the Finns.

Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate refers to substratum loanwords from unidentified non-Indo-European and non-Uralic languages that are found in various Finno-Ugric languages, most notably Sami. The presence of Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate in Sami languages was demonstrated by Ante Aikio. Janne Saarikivi points out that similar substrate words are present in Finnic languages as well, but in much smaller numbers.

The Finnic or Fennic peoples, sometimes simply called Finns, are the nations who speak languages traditionally classified in the Finnic language family, and which are thought to have originated in the region of the Volga River. The largest Finnic peoples by population are the Finns, the Estonians, the Mordvins (800,000), the Mari (570,000), the Udmurts (550,000), the Komis (330,000) and the Sami (100,000).

Meshchera is an extinct Uralic language. It was spoken around the left bank of the Middle Oka. Meshchera was either a Mordvinic or a Permic language. Pauli Rahkonen has suggested on the basis of toponymic evidence that it was a Permic or closely related language. Rahkonen's speculation has been criticized by Vladimir Napolskikh. Some Meshchera speaking people possibly assimilated into Mishar Tatars. However this theory is disputed.

Bjarmian languages are a group of extinct Finnic languages once spoken in Bjarmia, or the northern part of the Dvina basin. Vocabulary of the languages in Bjarmia can be reconstructed from toponyms in the Arkhangelsk region, and a few words are documented by Norse travelers. Also some Saamic toponyms can also be found in the Dvina basin.

Volkhov Chudes were a Finno-Ugric people living along the banks of the Volkhov River, who spoke a Finnic language. The Volkhov Chudes lived upstream from Staraya Ladoga. Rahkonen's studies of local toponyms confirm that the Volkhov Chudes spoke a Finnic language.