The Texas Revolution was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos against the centralist government of Mexico in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas. Although the uprising was part of a larger one, the Mexican Federalist War, that included other provinces opposed to the regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican government believed the United States had instigated the Texas insurrection with the goal of annexation. The Mexican Congress passed the Tornel Decree, declaring that any foreigners fighting against Mexican troops "will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag". Only the province of Texas succeeded in breaking with Mexico, establishing the Republic of Texas. It was eventually annexed by the United States.

The Battle of Chapultepec was a battle between American forces and Mexican forces holding the strategically located Chapultepec Castle just outside Mexico City, fought 13 September 1847 during the Mexican–American War. The building, sitting atop a 200-foot (61 m) hill, was an important position for the defense of the city.

The Battle of Palo Alto was the first major battle of the Mexican–American War and was fought on May 8, 1846, on disputed ground five miles (8 km) from the modern-day city of Brownsville, Texas. A force of some 3,700 Mexican troops – most of the Army of The North – led by General Mariano Arista engaged a force of approximately 2,300 United States troops – the Army of Occupation led by General Zachary Taylor.

The Thornton Affair, also known as the Thornton Skirmish, Thornton's Defeat, or Rancho Carricitos was a battle in 1846 between the military forces of the United States and Mexico 20 miles (32 km) west upriver from Zachary Taylor's camp along the Rio Grande. The much larger Mexican force defeated the Americans in the opening of hostilities, and was the primary justification for U.S. President James K. Polk's call to Congress to declare war.

The Battle of Buena Vista, known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between US forces, largely volunteers, under General Zachary Taylor, and the much larger Mexican Army under General Antonio López de Santa Anna. It took place near Buena Vista, a village in the state of Coahuila, about 12 km (7.5 mi) south of Saltillo, Mexico. La Angostura was the local name for the site. The outcome of the battle was ambiguous, with both sides claiming victory. Santa Anna's forces withdrew with war trophies of cannons and flags and left the field to the surprised U.S. forces, who had expected there to be another day of hard fighting.

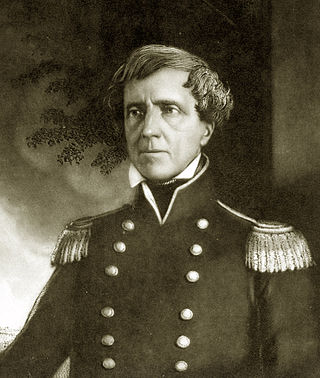

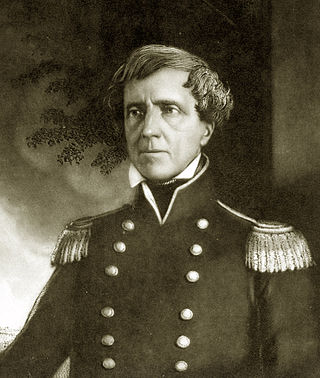

Stephen Watts Kearny was one of the foremost antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significant contributions in the Mexican–American War, especially the conquest of California. The Kearny code, proclaimed on September 22, 1846, in Santa Fe, established the law and government of the newly acquired territory of New Mexico and was named after him. His nephew was Major General Philip Kearny of American Civil War fame.

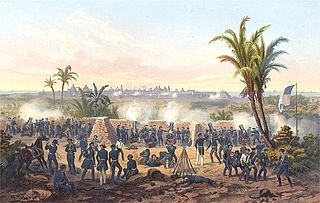

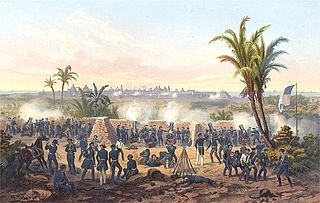

The Battle of Veracruz was a 20-day siege of the key Mexican beachhead seaport of Veracruz during the Mexican–American War. Lasting from March 9–29, 1847, it began with an amphibious assault conducted by United States military forces, and ended with the surrender and occupation of the city. U.S. forces then marched inland to Mexico City.

The Battle of San Pasqual, also spelled San Pascual, was a military encounter that occurred during the Mexican–American War in what is now the San Pasqual Valley community of the city of San Diego, California. The series of military skirmishes ended with both sides claiming victory, and the victor of the battle is still debated. On December 6 and December 7, 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny's US Army of the West, along with a small detachment of the California Battalion led by a Marine Lieutenant, engaged a small contingent of Californios and their Presidial Lancers Los Galgos, led by Major Andrés Pico. After U.S. reinforcements arrived, Kearny's troops were able to reach San Diego.

The Battle of Río San Gabriel, fought on 8 January 1847, was a decisive action of the California campaign of the Mexican–American War and occurred at a ford of the San Gabriel River, at what are today parts of the cities of Whittier, Pico Rivera and Montebello, about ten miles south-east of downtown Los Angeles.

The Pacific Squadron was part of the United States Navy squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval supplies and purchased food and obtained water from local ports of call in the Hawaiian Islands and towns on the Pacific Coast. Throughout the history of the Pacific Squadron, American ships fought against several enemies. Over one-half of the United States Navy would be sent to join the Pacific Squadron during the Mexican–American War. During the American Civil War, the squadron was reduced in size when its vessels were reassigned to Atlantic duty. When the Civil War was over, the squadron was reinforced again until being disbanded just after the turn of the 20th century.

The Battle of Churubusco took place on August 20, 1847, while Santa Anna's army was in retreat from the Battle of Contreras or Battle of Padierna during the Mexican–American War. It was the battle where the San Patricio Battalion, made up largely of US deserters, made their last stand against U.S. forces. The U.S. Army was victorious, outnumbering more than six-to-one the defending Mexican troops. After the battle, the U.S. Army was only 5 miles (8 km) away from Mexico City. 50 Saint Patrick's Battalion members were officially executed by the U.S. Army, all but two by hanging. Collectively, this was the largest mass execution in United States history.

The Battle of Contreras, also known as the Battle of Padierna, took place on 19–20 August 1847, in one of the final encounters of the Mexican–American War, as invading U.S. forces under Winfield Scott approached the Mexican capital. American forces surprised and then routed the Mexican forces of General Gabriel Valencia, who had disobeyed General Antonio López de Santa Anna's orders for his forces' placement. Although the battle was an overwhelming victory for U.S. forces, there are few depictions of it in contemporary popular prints. The armies re-engaged the next day in the Battle of Churubusco.

The Battle for Mexico City refers to the series of engagements from September 8 to September 15, 1847, in the general vicinity of Mexico City during the Mexican–American War. Included are major actions at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec, culminating with the fall of Mexico City. The U.S. Army under Winfield Scott won a major victory that ended the war.

The Battle of San Patricio was fought on February 27, 1836, between Texian rebels and the Mexican army, during the Texas Revolution. The battle occurred as a result of the outgrowth of the Texian Matamoros Expedition. The battle marked the start of the Goliad Campaign, the Mexican offensive to retake the Texas Gulf Coast. It took place in and around San Patricio.

The battle of Agua Dulce Creek was a skirmish during the Texas Revolution between Mexican troops and rebellious colonists of the Mexican province of Texas, known as Texians. As part of the Goliad Campaign to retake the Texas Gulf Coast, Mexican troops ambushed a group of Texians on March 2, 1836. The skirmish began approximately 26 miles (42 km) south of San Patricio, in territory belonging to the Mexican state of Tamaulipas.

The Army of the West was the name of the United States force commanded by Stephen W. Kearny during the Mexican–American War, which played a prominent role in the conquest of New Mexico and California.

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War, was an invasion of Mexico by the United States Army from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 American annexation of Texas, which Mexico still considered its territory because Mexico refused to recognize the Treaties of Velasco. This treaty was signed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna while he was captured by the Texian Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its Anglo-American citizens who had moved from the United States to Texas after 1822 wanted to be annexed by the United States.

The California Battalion was formed during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in present-day California, United States. It was led by U.S. Army Brevet Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont and composed of his cartographers, scouts and hunters and the California Volunteer Militia formed after the Bear Flag Revolt. The battalion's formation was officially authorized by Commodore Robert F. Stockton, commanding officer of the U.S. Navy Pacific Squadron.

Charles Augustus May (1818–1864) was an American officer of the United States Army who served in the Mexican War and other campaigns over a 25-year career. He is best known for successfully leading a cavalry charge against Mexican artillery at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma.

Affair at Galaxara Pass, November 24, 1847, was a U.S. Army victory of Gen. Joseph Lane, over the Mexican Army Light Corps, an irregular force under Gen. Joaquín Rea. The Light Corps had been the principal force harassing the U.S. Army line of communications on the National Road during Scott's campaign against Mexico City during the Mexican–American War. Following Lane's relief of the Siege of Puebla he moved against the Light Corps to end that threat.