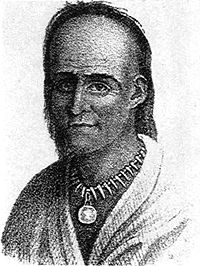

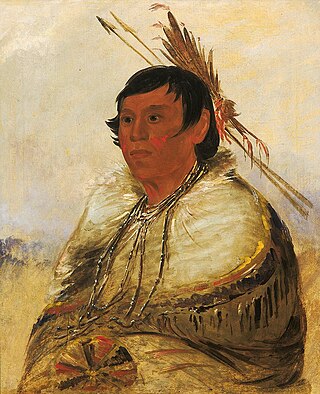

Little Turtle was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader then in the Northwest Territory," although he later signed several treaties ceding land, which caused him to lose his leader status during the battles which became a prelude to the War of 1812. In the 1790s, Mihšihkinaahkwa led a confederation of native warriors to several major victories against U.S. forces in the Northwest Indian Wars, sometimes called "Little Turtle's War", particularly St. Clair's defeat in 1791, wherein the confederation defeated General Arthur St. Clair, who lost 900 men in the most decisive loss by the U.S. Army against Native American forces.

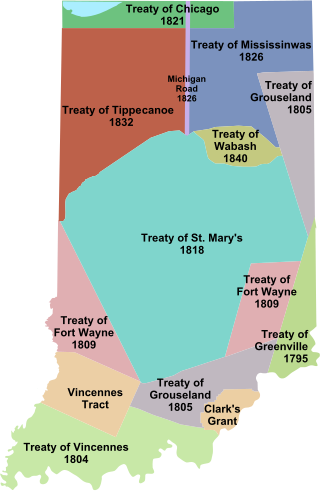

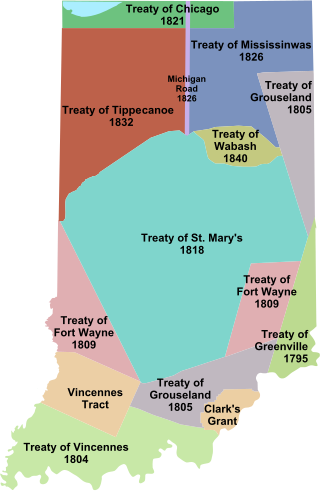

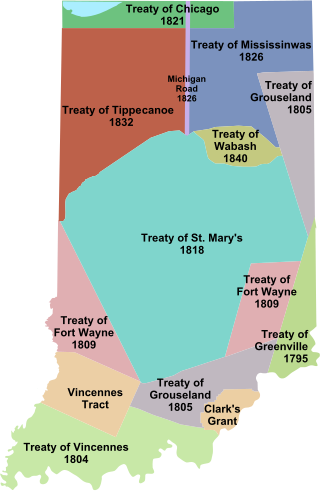

The Treaty of Greenville, also known to Americans as the Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., but formally titled A treaty of peace between the United States of America, and the tribes of Indians called the Wyandots, Delawares, Shawanees, Ottawas, Chippewas, Pattawatimas, Miamis, Eel Rivers, Weas, Kickapoos, Piankeshaws, and Kaskaskias was a 1795 treaty between the United States and indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory, including the Wyandot and Delaware peoples, that redefined the boundary between indigenous peoples' lands and territory for European American community settlement.

The Peoria are a Native American people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma headquartered in Miami, Oklahoma.

The Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern Confederacy. The United States Army considers it the first of the American Indian Wars.

The Wabash Confederacy, also referred to as the Wabash Indians or the Wabash tribes, was a number of 18th century Native American villagers in the area of the Wabash River in what are now the U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The Wabash Indians were primarily the Miami, Weas and Piankashaws, but also included Kickapoos, Mascoutens, and others. In that time and place, Native American tribes were smaller political units, and the villages along the Wabash were multi-tribal settlements with no centralized government. The confederacy, then, was a loose alliance of influential village leaders.

The Wea were a Miami-Illinois-speaking Native American tribe originally located in western Indiana. Historically, they were described as either being closely related to the Miami Tribe or a sub-tribe of Miami.

Kekionga, also known as Kiskakon or Pacan's Village, was the capital of the Miami tribe. It was located at the confluence of the Saint Joseph and Saint Marys rivers to form the Maumee River on the western edge of the Great Black Swamp in present-day Indiana. Over their respective decades of influence from colonial times to after the American Revolution, French and Indian Wars, and the Northwest Indian Wars, the French, British and Americans all established trading posts and forts at the large village, originally known as Fort Miami, due to its key location on the portage connecting Lake Erie to the Wabash and Mississippi rivers. The European-American town of Fort Wayne, Indiana started as a settlement around the American Fort Wayne stockade after the War of 1812.

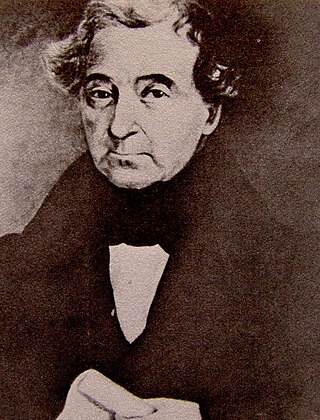

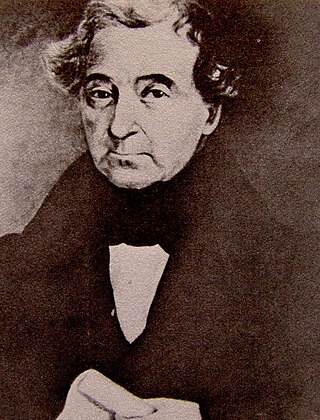

Jean Baptiste de Richardville, also known as Pinšiwa or Peshewa in the Miami-Illinois language or John Richardville in English, was the last akima 'civil chief' of the Miami people. He began his career in the 1790s as a fur trader who controlled an important portage connecting the Maumee River to the Little River in what became the present-day state of Indiana. Richardville emerged a principal chief in 1816 and remained a leader of the Miamis until his death in 1841. He was a signatory to the Treaty of Greenville (1795), as well as several later treaties between the U.S. government and the Miami people, most notably the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1803), the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809), the Treaty of Saint Mary's (1818), the Treaty of Mississinewas (1826), the treaty signed at the Forks of the Wabash (1838), and the Treaty of the Wabash (1840).

William Wells, also known as Apekonit, was the son-in-law of Chief Little Turtle of the Miami. He fought for the Miami in the Northwest Indian War. During the course of that war, he became a United States Army officer, and also served in the War of 1812.

The Treaty of St. Mary's may refer to one of six treaties concluded in fall of 1818 between the United States and Natives of central Indiana regarding purchase of Native land. The treaties were

Fort Miami, originally called Fort St. Philippe or Fort des Miamis, were a pair of French built palisade forts established at Kekionga, the principal village of the Miami. These forts were situated where the St. Joseph River and St. Marys River merge to form the Maumee River in Northeastern Indiana, where present day Fort Wayne is located. The forts and their key location on this confluence allowed for a significant hold on New France by whomever was able to control the area, both militarily for its strategic location and economically as it served as a gateway and hotbed for lucrative trade markets such as fur. It therefore played a pivotal role in a number of conflicts including the French and Indian Wars, Pontiac's War, and the Northwest Indian War, while other battles occurred nearby including La Balme's Defeat and the Harmar campaign. The first construct was a small trading post built by Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes around 1706, while the first fortified fort was finished in 1722, and the second in 1750. It is the predecessor to the Fort Wayne.

The Piankeshaw, Piankashaw or Pianguichia were members of the Miami tribe who lived apart from the rest of the Miami nation, therefore they were known as Peeyankihšiaki. When European settlers arrived in the region in the 1600s, the Piankeshaw lived in an area along the south central Wabash River that now includes western Indiana and Illinois. Their territory was to the north of Kickapoo and the south of the Wea. They were closely allied with the Wea, another group of Miamis. The Piankashaw were living along the Vermilion River in 1743.

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to itself as the United Indian Nations, at their Confederate Council. It was known infrequently as the Miami Confederacy since many contemporaneous federal officials overestimated the influence and numerical strength of the Miami tribes based on the size of their principal city, Kekionga.

Charles Beaubien was a French Canadian trader in the 18th century who became British Agent to the Miami Nation.

Pacanne was a leading Miami chief during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Son of The Turtle (Aquenackqua), he was the brother of Tacumwah, who was the mother of Chief Jean Baptiste Richardville. Their family owned and controlled the Long Portage, an 8-mile strip of land between the Maumee and Wabash Rivers used by traders travelling between Canada and Louisiana. As such, they were one of the most influential families of Kekionga.

Indian removals in Indiana followed a series of the land cession treaties made between 1795 and 1846 that led to the removal of most of the native tribes from Indiana. Some of the removals occurred prior to 1830, but most took place between 1830 and 1846. The Lenape (Delaware), Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee were removed in the 1820s and 1830s, but the Potawatomi and Miami removals in the 1830s and 1840s were more gradual and incomplete, and not all of Indiana's Native Americans voluntarily left the state. The most well-known resistance effort in Indiana was the forced removal of Chief Menominee and his Yellow River band of Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838, in which 859 Potawatomi were removed to Kansas and at least forty died on the journey west. The Miami were the last to be removed from Indiana, but tribal leaders delayed the process until 1846. Many of the Miami were permitted to remain on land allotments guaranteed to them under the Treaty of St. Mary's (1818) and subsequent treaties.

The Treaty of Fort Wayne was a treaty between the United States and several groups of Native Americans. The treaty was signed on June 7, 1803 and proclaimed December 26, 1803. It more precisely defined the boundaries of the Vincennes tract ceded to the United States by the Treaty of Greenville, 1795.

Tecumseh's confederacy was a confederation of indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region of North America that began to form in the early 19th century around the teaching of Tenskwatawa, called The Prophet by his followers. The confederation grew over several years and came to include several thousand warriors. Shawnee leader Tecumseh, the brother of The Prophet, developed into the leader of the group as early as 1808. Together, they worked to unite the various tribes against the European settlers who had been crossing the Appalachian Mountains and settling on their land.