The North-West Rebellion of 1885, also known as the North-West Resistance, was a rebellion by the Métis people under Louis Riel and an associated uprising by First Nations Cree and Assiniboine of the District of Saskatchewan against the Canadian government. Many Métis felt that Canada was not protecting their rights, their land, and their survival as a distinct people.

The Blackfoot Confederacy, Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi, is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people: the Siksika ("Blackfoot"), the Kainai or Blood, and two sections of the Peigan or Piikani – the Northern Piikani (Aapátohsipikáni) and the Southern Piikani. Broader definitions include groups such as the Tsúùtínà (Sarcee) and A'aninin who spoke quite different languages but allied with or joined the Blackfoot Confederacy.

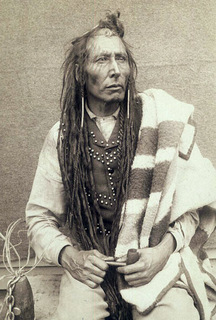

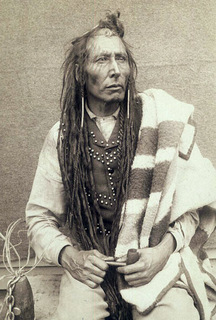

Big Bear, also known as Mistahi-maskwa, was a powerful and popular Cree chief who played many pivotal roles in Canadian history. He was appointed to chief of his band at the age of 40 upon the death of his father, Black Powder, under his father's harmonious and inclusive rule which directly impacted his own leadership. Big Bear is most notable for his involvement in Treaty 6 and the 1885 North-West Rebellion; he was one of the few chief leaders who objected to the signing of the treaty with the Canadian government. He felt that signing the treaty would ultimately have devastating effects on his nation as well as other Indigenous nations. This included losing the free nomadic lifestyle that his nation and others were accustomed to. Big Bear also took part in one of the last major battles between the Cree and the Blackfoot nations. He was one of the leaders to lead his people against the last, largest battle on the Canadian Plains.

Pîhtokahanapiwiyin, also known as Poundmaker, was a Plains Cree chief known as a peacemaker and defender of his people, the Poundmaker Cree Nation. His name denotes his special craft at leading buffalo into buffalo pounds (enclosures) for harvest.

Crowfoot or Isapo-Muxika was a chief of the Siksika First Nation. His parents, Istowun-eh'pata and Axkahp-say-pi, were Kainai. He was five years old when Istowun-eh'pata was killed during a raid on the Crow tribe, and, a year later, his mother remarried to Akay-nehka-simi of the Siksika people among whom he was brought up. Crowfoot was a warrior who fought in as many as nineteen battles and sustained many injuries, but he tried to obtain peace instead of warfare. Crowfoot is well known for his involvement in Treaty Number 7 and did much negotiating for his people. While many believe Chief Crowfoot had no part in the North-West Rebellion, he did in fact participate to an extent due to his son's connection to the conflict. Crowfoot died of tuberculosis at Blackfoot Crossing on April 25, 1890. Eight hundred of his tribe attended his funeral, along with government dignitaries. In 2008, Chief Crowfoot was inducted into the North America Railway Hall of Fame where he was recognized for his contributions to the railway industry. Crowfoot is well known for his contributions to the Blackfoot nation, and has many memorials to signify his accomplishments.

Treaty 7 is an agreement between the Crown and several, mainly Blackfoot, First Nation band governments in what is today the southern portion of Alberta. The idea of developing treaties for Blackfoot lands was brought to Blackfoot chief Crowfoot by John McDougall in 1875. It was concluded on September 22nd, 1877 and December 4th, 1877. The agreement was signed at the Blackfoot Crossing of the Bow River, at the present-day Siksika Nation reserve, approximately 100 km (62 mi) east of Calgary, Alberta. Chief Crowfoot was one of the signatories to Treaty 7. Another signing on this treaty occurred on December 4, 1877 to accommodate some Blackfoot leaders who were not present at the primary September 1877 signing.

A Tribal Council is an association of First Nations bands in Canada, generally along regional, ethnic or linguistic lines.

First Nations in Alberta are a group of people who live in the Canadian province of Alberta. The First Nations are peoples recognized as Indigenous peoples or Plains Indians in Canada excluding the Inuit and the Métis. According to the 2011 Census, a population of 116,670 Albertans self-identified as First Nations. Specifically there were 96,730 First Nations people with registered Indian Status and 19,945 First Nations people without registered Indian Status. Alberta has the third largest First Nations population among the provinces and territories. From this total population, 47.3% of the population lives on an Indian reserve and the other 52.7% live in urban centres. According to the 2011 Census, the First Nations population in Edmonton totalled at 31,780, which is the second highest for any city in Canada. The First Nations population in Calgary, in reference to the 2011 Census, totalled at 17,040. There are 48 First Nations or "bands" in Alberta, belonging to nine different ethnic groups or "tribes" based on their ancestral languages.

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specifically, Treaty 6 is an agreement between the Crown and the Plains and Woods Cree, Assiniboine, and other band governments at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt. Key figures, representing the Crown, involved in the negotiations were Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories; James McKay, The Minister of Agriculture for Manitoba; and W.J. Christie, the Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company. Chief Mistawasis and Chief Ahtahkakoop represented the Carlton Cree.

Treaty 4 is a treaty established between Queen Victoria and the Cree and Saulteaux First Nation band governments. The area covered by Treaty 4 represents most of current day southern Saskatchewan, plus small portions of what are today western Manitoba and southeastern Alberta. This treaty is also called the Qu'Appelle Treaty, as its first signings were conducted at Fort Qu'Appelle, North-West Territories, on 15 September 1874. Additional signings or adhesions continued until September 1877. This treaty is the only indigenous treaty in Canada that has a corresponding indigenous interpretation.

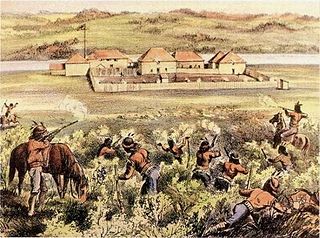

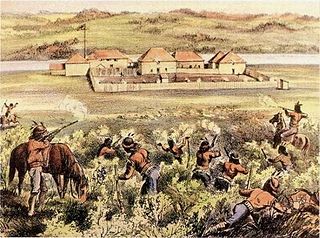

Fort Pitt Provincial Park is a provincial park in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Fort Pitt was a fort built in 1829 by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) that also served as a trading post on the North Saskatchewan River in Rupert's Land. It was built at the direction of Chief Factor John Rowand, previously of Fort Edmonton, in order to trade for bison hides, meat and pemmican. Pemmican, dried buffalo meat, was required as provisions for HBC's northern trading posts.

The Battle of the Belly River was the last major conflict between the Cree and the Blackfoot Confederacy, and the last major battle between First Nations on Canadian soil.

The Red Pheasant Cree Nation is a Plains Cree First Nations band government in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The band's sole reserve, Red Pheasant 108, is 33 km (21 mi) south of North Battleford.

Ahtahkakoop First Nation is a Cree First Nation band government in Shell Lake, Saskatchewan, Canada. The Ahtahkakoop First Nation government and community is located on Ahtahkakoop 104, 72 kilometers northwest of Prince Albert and is 17,347 hectares in size.

The Looting of Battleford began at the end of March, 1885, during the North-West Rebellion, in the town of Battleford, Saskatchewan, then a part of the Northwest Territories.

Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park is a complex of historic sites on the Siksika 146 Indian reserve in Alberta, Canada. This crossing of the Bow River was traditionally a bison-hunting and gathering place for the Siksika people and their allies in the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Father Con Scollen OMI. was an Irish Catholic, Missionary priest who lived among and evangelized the Blackfoot, Cree and Métis peoples on the Canadian Prairies and in northern Montana in the United States. He also ministered to the Ktunaxa people (Kootenay) on their annual visits to Fort Macleod, from British Columbia. Later he worked among the indigenous peoples in modern-day North Dakota and Wyoming, then Nebraska, Kansas, Illinois and Ohio.

Ahtahkakoop (c. 1816 – 1896) was a Chief of the House Cree (Wāskahikaniwiyiniwak) division of the Plains Cree, who led his people through the transition from hunter and warrior to farmer, and from traditional indigenous spiritualism to Christianity during the last third of the 19th century.

The Iron Confederacy or Iron Confederation was a political and military alliance of Plains Natives of what is now Western Canada and the northern United States. This confederacy included various individual bands that formed political, hunting and military alliances in defense against common enemies. The ethnic groups that made up the Confederacy were the branches of the Cree that moved onto the Great Plains around 1740, the Saulteaux, the Nakoda or Stoney people also called Pwat or Assiniboine, and the Métis and Haudenosaunee. The Confederacy rose to predominance on the northern Plains during the height of the North American fur trade when they operated as middlemen controlling the flow of European goods, particularly guns and ammunition, to other Indigenous nations, and the flow of furs to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and North West Company (NWC) trading posts. Its peoples later also played a major part in the bison (buffalo) hunt, and the pemmican trade. The decline of the fur trade and the collapse of the bison herds sapped the power of the Confederacy after the 1860s, and it could no longer act as a barrier to U.S. and Canadian expansion.

Sweet Grass was a chief of the Cree in the 1860s and 1870s in western Canada. He worked with other chiefs and bands to participate in raids with enemy tribes. While a chief, Sweet Grass noticed the starvation and economic hardship the Cree were facing. This propelled him to work with the Canadian and eventually sign Treaty Six. Sweet Grass believed that working alongside the government was one of the only solutions to the daily hardship the Cree were faced with. The Sweet Grass Reserve west of Battleford, Saskatchewan was named in his honor and is still functioning today.