Deuteronomy is the fifth book of the Torah, where it is called Devarim and the fifth book of the Christian Old Testament.

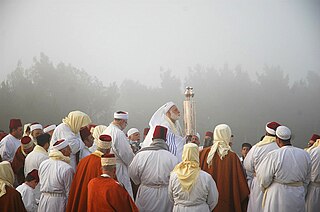

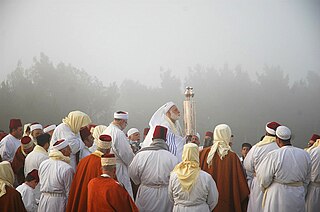

Samaritanism is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion. It comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Samaritan people, who originate from the Hebrews and Israelites and began to emerge as a relatively distinct group after the Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the Iron Age. Central to the faith is the Samaritan Pentateuch, which Samaritans believe is the original and unchanged version of the Torah.

Samaritans, also known as Israelite Samaritans, are an ethnoreligious group who originate from the ancient Israelites. They are native to the Levant and adhere to Samaritanism, an Abrahamic ethnic religion similar to Judaism, but differing in several important aspects.

Samaria is the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron, used as a historical and biblical name for the central region of Israel, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is known to the Palestinians in Arabic under two names, Samirah, and Mount Nablus.

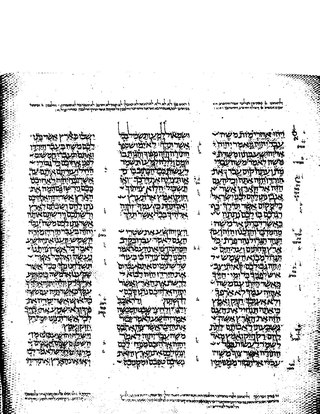

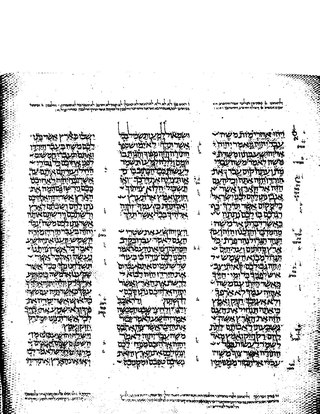

The Torah is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is known as the Pentateuch or the Five Books of Moses by Christians. It is also known as the Written Torah in Jewish tradition. If meant for liturgic purposes, it takes the form of a Torah scroll. If in bound book form, it is called Chumash, and is usually printed with the rabbinic commentaries.

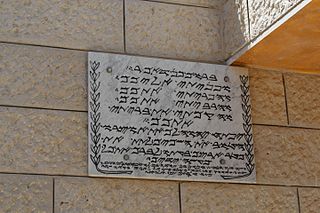

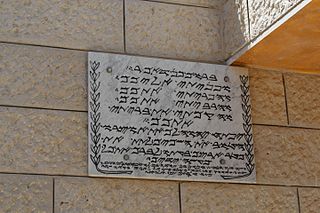

The Samaritan Torah, commonly called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is a text of the Torah written in the Samaritan script and used as sacred scripture by the Samaritans. It dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Hebrew Bible that existed during the Second Temple period, and constitutes the entire biblical canon in Samaritanism.

Moriah is the name given to a mountainous region in the Book of Genesis, where the binding of Isaac by Abraham is said to have taken place. Jews identify the region mentioned in Genesis and the specific mountain in which the near-sacrifice is said to have occurred with "Mount Moriah", mentioned in the Book of Chronicles as the place where Solomon's Temple is said to have been built, and both these locations are also identified with the current Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The Samaritan Torah, on the other hand, transliterates the place mentioned for the binding of Isaac as Moreh, a name for the region near modern-day Nablus. It is believed by the Samaritans that the near-sacrifice actually took place on Mount Gerizim, near Nablus in the West Bank.

Givat HaMoreh is a hill in northern Israel on the northeast side of the Jezreel Valley. The highest peak reaches an altitude of 515 metres (1,690 ft), while the bottom of the Jezreel Valley is situated at an altitude of 50–100 metres (160–330 ft). North of it are the plains of the Lower Galilee and Mount Tabor. To the east, Giv'at HaMoreh connects to the Issachar Plateau. To the southeast it descends into the Harod Valley, where the 'Ain Jalut flows eastwards into the Jordan Valley.

Shechem, also spelled Sichem, was an ancient city in the southern Levant. Mentioned as a Canaanite city in the Amarna Letters, it later appears in the Hebrew Bible as the first capital of the Kingdom of Israel following the split of the United Monarchy. According to Joshua 21:20–21, it was located in the tribal territorial allotment of the tribe of Ephraim. Shechem declined after the fall of the northern Kingdom of Israel. The city later regained its importance as a prominent Samaritan center during the Hellenistic period.

Abimelech or Abimelek was the king of Shechem and a son of biblical judge Gideon. His name can best be interpreted as "my father is king", claiming the inherited right to rule. He is introduced in Judges 8:31 as the son of Gideon and his Shechemite concubine, and the biblical account of his reign is described in chapter nine of the Book of Judges. According to the Bible, he was an unprincipled and ambitious ruler who often engaged in war against his own subjects.

Eli was, according to the Book of Samuel, a priest and a judge of the Israelites in the city of Shiloh, ancient Israel. When Hannah came to Shiloh to pray for a son, Eli initially accused her of drunkenness, but when she protested her innocence, Eli wished her well. Hannah's eventual child, Samuel, was raised by Eli in the tabernacle. When Eli failed to rein in the abusive behavior of his own sons, God promised to punish his family, which resulted in the death of Eli's sons at the Battle of Aphek where the Ark of the Covenant was also captured. When Eli heard the news of the captured Ark, he fell from his seat, broke his neck, and died. Later biblical passages mention the fortunes of several of Eli's descendants.

The Law of Moses, also called the Mosaic Law, is the law said to have been revealed to Moses by God. The term primarily refers to the Torah or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible.

Mount Gerizim is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinity of the Palestinian city of Nablus and the biblical city of Shechem. It forms the southern side of the valley in which Nablus is situated, the northern side being formed by Mount Ebal. The mountain is one of the highest peaks in the West Bank and rises to 881 m (2,890 ft) above sea level, 70 m (230 ft) lower than Mount Ebal. The mountain is particularly steep on the northern side, is sparsely covered at the top with shrubbery, and lower down there is a spring with a high yield of fresh water. For the Samaritan people, most of whom live around it, Mount Gerizim is considered the holiest place on Earth.

In the Torah, Ithamar was the fourth son of Aaron the High Priest. Following the construction of the Tabernacle, he was responsible for recording an inventory to ensure that the constructed Tabernacle and its contents conformed to the vision given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai.

Ki Tavo, Ki Thavo, Ki Tabo, Ki Thabo, or Ki Savo is the 50th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the seventh in the Book of Deuteronomy. It comprises Deuteronomy 26:1–29:8. The parashah tells of the ceremony of the first fruits, tithes, and the blessings from observance and curses from violation of the law.

Adam Zertal was an Israeli archaeologist and a tenured professor at the University of Haifa.

The earliest known precursor to Hebrew, an inscription in the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, is the Khirbet Qeiyafa Inscription, if it can be considered Hebrew at that early a stage.

Joshua 8 is the eighth chapter of the Book of Joshua in the Hebrew Bible or in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. According to Jewish tradition the book was attributed to the Joshua, with additions by the high priests Eleazar and Phinehas, but modern scholars view it as part of the Deuteronomistic History, which spans the books of Deuteronomy to 2 Kings, attributed to nationalistic and devotedly Yahwistic writers during the time of the reformer Judean king Josiah in 7th century BCE. This chapter focuses on the conquest of Ai under the leadership of Joshua and the renewal of covenant on Mounts Ebal and Gerizim, a part of a section comprising Joshua 5:13–12:24 about the conquest of Canaan.

The Iron Age I Structure on Mt. Ebal, also known as the Mount Ebal site, Mount Ebal's Altar, and Joshua's Altar, is an archeological site dated to the Iron Age I, located on Mount Ebal, West Bank.

The Mount Ebal curse tablet is a supposedly inscribed folded lead sheet reportedly found on Mount Ebal in the West Bank, near Nablus, in December 2019. The artifact, discovered by a team of archaeologists led by Scott Stripling, was found by wet-sifting the discarded material from Adam Zertal's 1982–1989 archaeological excavation.