Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs and practices of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia between circa 3500 BC and 400 AD, after which they largely gave way to Syriac Christianity. The religious development of Mesopotamia and Mesopotamian culture in general was not particularly influenced by the movements of the various peoples into and throughout the area, particularly the south. Rather, Mesopotamian religion was a consistent and coherent tradition which adapted to the internal needs of its adherents over millennia of development.

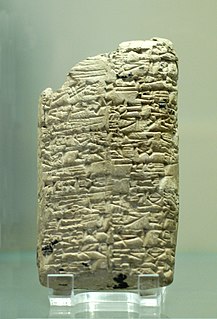

Akkadian literature is the ancient literature written in the Akkadian language written in Mesopotamia during the period spanning the Middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age.

Nintinugga was a Babylonian goddess of healing, the consort of Ninurta. She is identical with the goddess of Akkadian mythology, known as Bau, Baba though it would seem that the two were originally independent. Later as Gula and in medical incantations, Bēlet or Balāti, also as the Azugallatu the "great healer",same as her son Damu. Other names borne by this goddess are Nin-Karrak, Nin Ezen, Ga-tum-dug and Nm-din-dug. Her epithets are "great healer of the land" and "great healer of the black-headed ones", a "herb grower", "the lady who makes the broken up whole again", and "creates life in the land", making her a vegetation/fertility goddess endowed with regenerative power. She was the daughter of An and a wife of Ninurta. She had seven daughters, including Hegir-Nuna (Gangir).

A curse is any expressed wish that some form of adversity or misfortune will befall or attach to some other entity: one or more persons, a place, or an object. In particular, "curse" may refer to such a wish or pronouncement made effective by a supernatural or spiritual power, such as a god or gods, a spirit, or a natural force, or else as a kind of spell by magic or witchcraft; in the latter sense, a curse can also be called a hex or a jinx. In many belief systems, the curse itself is considered to have some causative force in the result. To reverse or eliminate a curse is sometimes called "removal" or "breaking", as the spell has to be dispelled, and is often requiring elaborate rituals or prayers.

The udug, later known in Akkadian as the utukku, were an ambiguous class of demons from ancient Mesopotamian mythology who were sometimes thought of as good and sometimes as evil. In exorcism texts, the "good udug" is sometimes invoked against the "evil udug". The word is generally ambiguous and is sometimes used to refer to demons as a whole rather than a specific kind of demon. No visual representations of the udug have yet been identified, but descriptions of it ascribe to it features often given to other ancient Mesopotamian demons: a dark shadow, absence of light surrounding it, poison, and a deafening voice. The surviving ancient Mesopotamian texts giving instructions for exorcizing the evil udug are known as the Udug Hul texts. These texts emphasize the evil udug's role in causing disease and the exorcist's role in curing the disease.

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology Asaruludu is one of the Anunnaku. His name is also spelled Asarludu, Asarluhi, and Namshub. The etymology and meaning of his name are unclear.

An incantation, or a spell, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial rituals or prayers. Other words synonymous with incantation is spells, charms or to bewitch. In the world of magic, the incantations are said to be performed by wizards, witches and fairies.

The god Ninkilim, inscribed dnin-PEŠ2, is a widely referenced Mesopotamian deity from Sumerian to later Babylonian periods whose minions include wildlife in general and vermin in particular. His name, Nin-kilim, means "Lord Rodent," where rodent, pronounced šikku but rendered nin-ka6, is a homograph.

The Ritual of Restoration is a fictional curse from the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel. It has been performed three times on screen.

Ritual of the Bacabs is the name given to a manuscript from the Yucatán containing shamanistic incantations written in the Yucatec Maya language. The manuscript was given its name by Mayanist William E. Gates due to the frequent mentioning of the Maya deities known as the Bacabs. A printed indulgence on the last pages dates it to 1779.

The Maqlû, “burning,” series is an Akkadian incantation text which concerns the performance of a rather lengthy anti-witchcraft, or kišpū, ritual. In its mature form, probably composed in the early first millennium BC, it comprises eight tablets of nearly a hundred incantations and a ritual tablet, giving incipits and directions for the ceremony. This was performed over the course of a single night in the month of Abu (July/August) when the perambulations of the spirits to and from the netherworld made them especially vulnerable to its spells. It was the subject of a letter from the exorcist Nabû-nādin-šumi and the Assyrian king Esarhaddon. It seems to have evolved from an earlier short-form with only ten incantations to be performed in a morning ceremony, whose first incantation begins: Šamaš annûtu șalmū ēpišiya.

Kulullû, inscribed ku6-lú-u18/19-lu, "Fish-Man", an ancient Mesopotamian mythical monster possibly inherited by Marduk from his father Ea. In later Assyrian mythology he was associated with kuliltu, "Fish-Woman", and statues of them were apparently located in the Nabû temple in Nimrud, ancient Kalhu, as referenced on a contemporary administrative text.

The NAM-BÚR-BI are magical texts which take the form of incantations. They were named for a series of prophylactic Babylonian and Assyrian rituals to avert inauspicious portents before they took on tangible form. At the core of these rituals was an appeal by the subject of the sinister omen to the divine judicial court to obtain a change to his impending fate. From the corpus of Babylonian-Assyrian religious texts that has survived, there are approximately one hundred and forty texts, many preserved in several copies, to which this label may be applied.

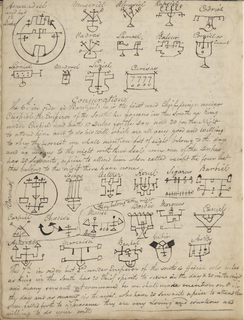

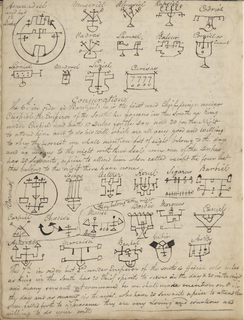

The work šēp lemutti ina bīt amēli parāsu, “to block the entry of the enemy into someone’s house,” also referred to as ana nasāḫ šēp lemutti, "to expel the 'foot of evil'," is a first millennium BC Mesopotamian ritual text idiom well attested in the apodoses of divinations which provides the procedures to protect a house with magical defenses from demonic attack. Sickness, death, misfortune, and ominous occurrences in the house, were perceived to be the result of actions of the hordes of demons from the netherworld. These involve the use of apotropaic figurines, whose god, apkallu, and monster alter-egos, are invoked by an incantation, and their interment in various parts of a private house. Archaeological excavation has uncovered many instances of small figurines buried in boxes in the foundations of structures such as palaces and domestic houses of the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods.

Mîs-pî, inscribed KA-LUḪ.Ù.DA and meaning “washing of the mouth,” is an ancient Mesopotamian ritual and incantation series for the cultic induction or vivification of a newly manufactured divine idol. It involved around eleven stages: in the city, countryside and temple, the workshop, a procession to the river, then beside the river bank, a procession to the orchard, in reed huts and tents in the circle of the orchard, to the gate of the temple, the niche of the sanctuary and finally, at the quay of the Apsû, accompanied by invocations to the nine great gods, the nine patron gods of craftsmen, and assorted astrological bodies.

Zisurrû, meaning “magic circle drawn with flour,” and inscribed ZÌ-SUR-RA-a, was an ancient Mesopotamian means of delineating, purifying and protecting from evil by the enclosing of a ritual space in a circle of flour. It involved ritual drawings with a variety of powdered cereals to counter different threats and is accompanied by the gloss: SAG.BA SAG.BA, Akkadian: māmīt māmīt, the curse from a broken oath, in the Exorcists Manual, where it refers to a specific ritual on two tablets the first of which is extant.

Ḫulbazizi, inscribed in cuneiform phonetically Ḫul.ba.zi.zi, “the Evil is Eradicated” or more literally "Evil (be) gone", is an ancient Mesopotamian exorcistic incantation series extant in earlier Sumerian and later Akkadian forms, the language switch taking place in the late Bronze Age, directed at every sort of evil, including a spell against everything scary that hides below one’s bed at night, depicted on an amulet with the terrified subject seated upright on his bed while a small dragon emerges from beneath to be confronted by a third figure.

The incantation series inscribed in cuneiform Sumerograms as ÉN SAG.GIG.GA.MEŠ, Akkadian: muruṣ qaqqadi, “headache”, is an ancient Mesopotamian nine-tablet collection of magical prescriptions against the demon that caused grave disease characterized by a headache. Some of its incantations seem to have become incorporated into the later Assyrian work muššu’u, “rubbing”. It is listed on the ninth line of the KAR44, the work known as the Exorcists Manual, a compendium of the works of the āšipūtu, craft of exorcism, prefixed by the gloss sa.kik.ke4, a phonetic rendition of the series’ opening incipit, én sag-gig é-kur-ta nam-ta-è.

Atta mannu, “who are you?”, inscribed in cuneiform Sumerograms: A.BA.ME.EN.MEŠ, was an ancient Mesopotamian ritual or conjuration of uncertain content.