John Hoyer Updike was an American novelist, poet, short-story writer, art critic, and literary critic. One of only four writers to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction more than once, Updike published more than twenty novels, more than a dozen short-story collections, as well as poetry, art and literary criticism and children's books during his career.

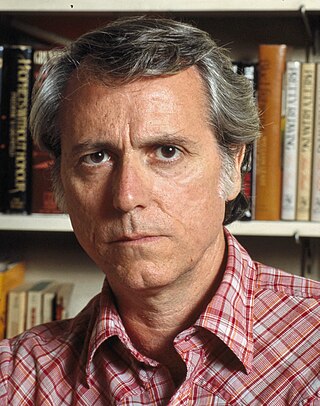

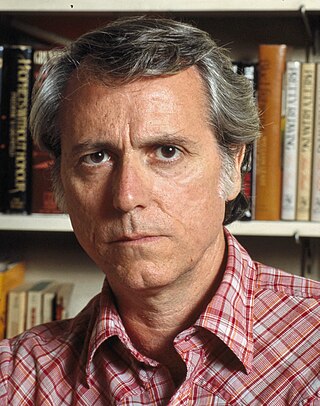

Donald Richard DeLillo is an American novelist, short story writer, playwright, screenwriter and essayist. His works have covered subjects as diverse as television, nuclear war, the complexities of language, art, the advent of the Digital Age, mathematics, politics, economics, and sports.

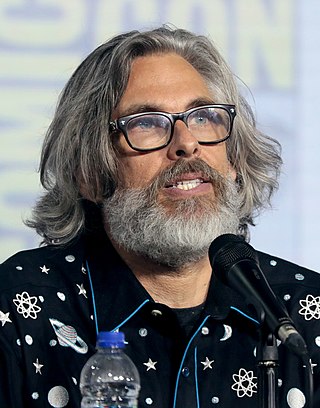

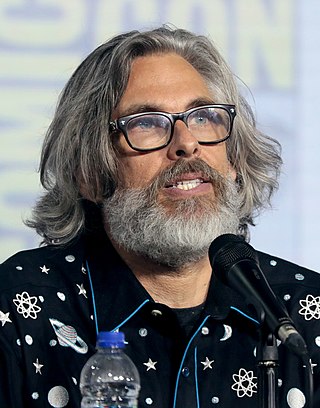

Michael Chabon is an American novelist, screenwriter, columnist, and short story writer. Born in Washington, D.C., he spent a year studying at Carnegie Mellon University before transferring to the University of Pittsburgh, graduating in 1984. He subsequently received a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from the University of California, Irvine.

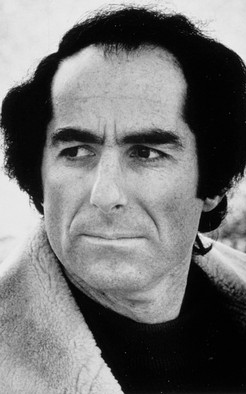

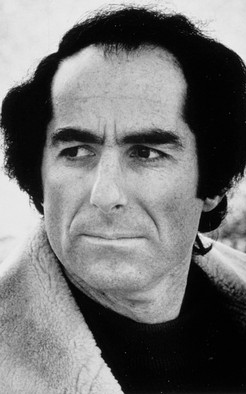

Philip Milton Roth was an American novelist and short-story writer. Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical character, for philosophically and formally blurring the distinction between reality and fiction, for its "sensual, ingenious style" and for its provocative explorations of American identity. He first gained attention with the 1959 short story collection Goodbye, Columbus, which won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction. Ten years later, he published the bestseller Portnoy's Complaint. Nathan Zuckerman, Roth's literary alter ego, narrates several of his books. A fictionalized Philip Roth narrates some of his others, such as the alternate history The Plot Against America.

Octavia Estelle Butler was an American science fiction author and a multiple recipient of the Hugo and Nebula awards. In 1995, Butler became the first science-fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship.

Thomas Coraghessan Boyle is an American novelist and short story writer. Since the mid-1970s, he has published nineteen novels and more than 150 short stories. He won the PEN/Faulkner award in 1988, for his third novel, World's End, which recounts 300 years in upstate New York.

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow was an American novelist, editor, and professor, best known for his works of historical fiction.

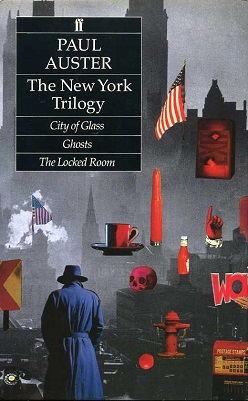

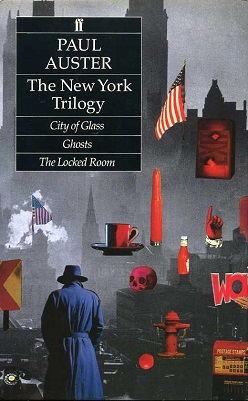

The New York Trilogy is a series of novels by American writer Paul Auster. Originally published sequentially as City of Glass (1985), Ghosts (1986) and The Locked Room (1986), it has since been collected into a single volume. The Trilogy is a postmodern interpretation of detective and mystery fiction, exploring various philosophical themes.

Siri Hustvedt is an American novelist and essayist. Hustvedt is the author of a book of poetry, seven novels, two books of essays, and several works of non-fiction. Her books include The Blindfold (1992), The Enchantment of Lily Dahl (1996), What I Loved (2003), for which she is best known, A Plea for Eros (2006), The Sorrows of an American (2008), The Shaking Woman or A History of My Nerves (2010), The Summer Without Men (2011), Living, Thinking, Looking (2012), The Blazing World (2014), and Memories of the Future (2019). What I Loved and The Summer Without Men were international bestsellers. Her work has been translated into over thirty languages.

Jane Smiley is an American novelist. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1992 for her novel A Thousand Acres (1991).

The Book of Illusions is a novel by American writer Paul Auster, published in 2002. It was nominated for the International Dublin Literary Award in 2004.

Junot Díaz is a Dominican-American writer, creative writing professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a former fiction editor at Boston Review. He also serves on the board of advisers for Freedom University, a volunteer organization in Georgia that provides post-secondary instruction to undocumented immigrants. Central to Díaz's work is the immigrant experience, particularly the Latino immigrant experience.

Lydia Davis is an American short story writer, novelist, essayist, and translator from French and other languages, who often writes short short stories. Davis has produced several new translations of French literary classics, including Swann's Way by Marcel Proust and Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert.

Adam Haslett is an American fiction writer and journalist. His debut short story collection, You Are Not a Stranger Here, and his second novel, Imagine Me Gone, were both finalists for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He has been awarded fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the American Academy in Berlin. In 2017, he won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Jennifer Egan is an American novelist and short-story writer. Her novel A Visit from the Goon Squad won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction. As of February 28, 2018, she is the president of PEN America.

Joseph O'Neill is an Irish novelist and non-fiction writer. O'Neill's novel Netherland was awarded the 2009 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction and the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Award.

Tom De Haven is an American author, editor, journalist, and writing teacher. His recurring subjects include literary and film noir, the Hollywood studio system and the American comics industry. De Haven is noted for his comics-themed novels, including the Derby Dugan trilogy and It's Superman.

Tinkers is a 2009 first novel by American author Paul Harding. The novel tells the stories of George Washington Crosby, an elderly clock repairman, and of his father, Howard. On his deathbed, George remembers his father, who was a tinker selling household goods from a donkey-drawn cart and who struggled with epilepsy. The novel was published by Bellevue Literary Press, a sister organization of the Bellevue Literary Review.

The Moor's Account is a novel by Laila Lalami. It was a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist in 2015.

Mitchell S. Jackson is an American writer. He is the author of the 2013 novel The Residue Years, as well as Oversoul (2012), an ebook collection of essays and short stories. Jackson is a Whiting Award recipient and a former winner of the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence. In 2021, while an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Chicago, he won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Magazine Award for Feature Writing for his profile of Ahmaud Arbery for Runner's World. As of 2021, Jackson is the John O. Whiteman Dean's Distinguished Professor in the Department of English at Arizona State University.