Hel is a female being in Norse mythology who is said to preside over an underworld realm of the same name, where she receives a portion of the dead. Hel is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century. In addition, she is mentioned in poems recorded in Heimskringla and Egils saga that date from the 9th and 10th centuries, respectively. An episode in the Latin work Gesta Danorum, written in the 12th century by Saxo Grammaticus, is generally considered to refer to Hel, and Hel may appear on various Migration Period bracteates.

The Wild Hunt is a folklore motif occurring across various northern European cultures. Wild Hunts typically involve a chase led by a mythological figure escorted by a ghostly or supernatural group of hunters engaged in pursuit. The leader of the hunt is often a named figure associated with Odin in Germanic legends, but may variously be a historical or legendary figure like Theodoric the Great, the Danish king Valdemar Atterdag, the dragon slayer Sigurd, the Welsh psychopomp Gwyn ap Nudd, biblical figures such as Herod, Cain, Gabriel, or the Devil, or an unidentified lost soul or spirit either male or female. The hunters are generally the souls of the dead or ghostly dogs, sometimes fairies, valkyries, or elves.

Ēostre is a West Germanic spring goddess. The name is reflected in Old English: *Ēastre, Old High German: *Ôstara, and Old Saxon: *Āsteron. By way of the Germanic month bearing her name, she is the namesake of the festival of Easter in some languages. The Old English deity Ēostre is attested solely by Bede in his 8th-century work The Reckoning of Time, where Bede states that during Ēosturmōnaþ, pagan Anglo-Saxons had held feasts in Ēostre's honour, but that this tradition had died out by his time, replaced by the Christian Paschal month, a celebration of the resurrection of Jesus.

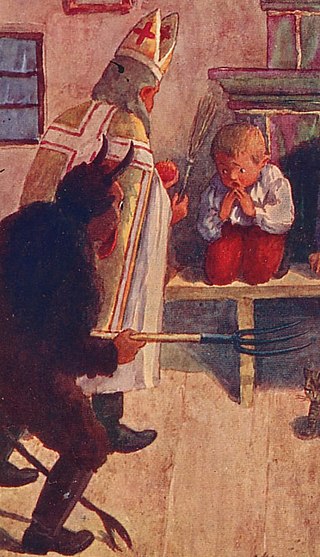

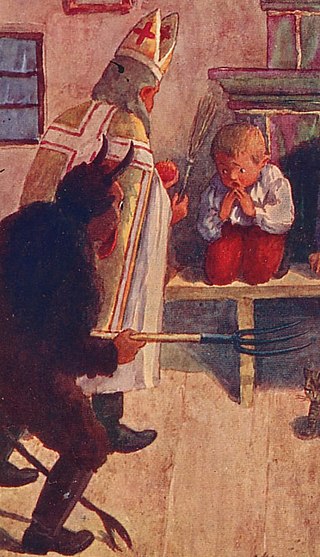

The companions of Saint Nicholas are a group of closely related figures who accompany Saint Nicholas throughout the territories formerly in the Holy Roman Empire or the countries that it influenced culturally. These characters act as a foil to the benevolent Christmas gift-bringer, threatening to thrash or abduct disobedient children. Jacob Grimm associated this character with the pre-Christian house spirit which could be benevolent or malicious, but whose mischievous side was emphasized after Christianization. The association of the Christmas gift-bringer with elves has parallels in English and Scandinavian folklore, and is ultimately and remotely connected to the Christmas elf in modern American folklore.

In Germanic paganism, Nerthus is a goddess associated with a ceremonial wagon procession. Nerthus is attested by first century AD Roman historian Tacitus in his ethnographic work Germania.

In Italian folklore, the Befana is an old woman or witch who delivers gifts to children throughout Italy on Epiphany Eve in a similar way to Santa Claus or the Three Magi Kings.

Mention of textiles in folklore is ancient, and its lost mythic lore probably accompanied the early spread of this art. Textiles have also been associated in several cultures with spiders in mythology.

The central and eastern Alps of Europe are rich in folklore traditions dating back to pre-Christian times, with surviving elements originating from Germanic, Gaulish (Gallo-Roman), Slavic (Carantanian) and Raetian culture.

Swiss folklore describes a collection of local stories, celebrations, and customs of the alpine and sub-alpine peoples that occupy Switzerland. The country of Switzerland is made up of several distinct cultures including German, French, Italian, as well as the Romansh speaking population of Graubünden. Each group has its own unique folkloric tradition.

German folklore is the folk tradition which has developed in Germany over a number of centuries. Seeing as Germany was divided into numerous polities for most of its history, this term might both refer to the folklore of Germany proper and of all German-speaking countries, this wider definition including folklore of Austria and Liechtenstein as well as the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Italy.

"Frau Holle" is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in Children's and Household Tales in 1812. It is of Aarne-Thompson type 480.

The Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht, Fasnacht or Fasnat/Faschnat is the pre-Lenten carnival of Alemannic folklore in Switzerland, southern Germany, Alsace and Vorarlberg.

In German folklore, the Weiße Frauen are elven-like spirits that may have derived from Germanic paganism in the form of legends of light elves. The Dutch Witte Wieven went at least as far back as the 7th century, and their mistranslation as White Women instead of the original Wise Women can be explained by the Dutch word wit also meaning white. They are described as beautiful and enchanted creatures who appear at noon and can be seen sitting in the sunshine brushing their hair or bathing in a brook. They may be guarding treasure or haunting castles. They entreat mortals to break their spell, but this is always unsuccessful. The mythology dates back at least to the Middle Ages and was known in the present-day area of Germany.

In Germanic paganism, Tamfana is a goddess. The destruction of a temple dedicated to the goddess is recorded by Roman senator Tacitus to have occurred during a massacre of the Germanic Marsi by forces led by Roman general Germanicus. Scholars have analyzed the name of the goddess and have advanced theories regarding her role in Germanic paganism.

Lotte Motz, born Lotte Edlis was an Austrian-American scholar, obtaining a Ph.D. in German and philology, who published four books and many scholarly papers, primarily in the fields of Germanic mythology and folklore.

In Germanic mythology, an idis is a divine female being. Idis is cognate to Old High German itis and Old English ides, meaning 'well-respected and dignified woman.' Connections have been assumed or theorized between the idisi and the North Germanic dísir; female beings associated with fate, as well as the amended place name Idistaviso.

*Frijjō ("Frigg-Frija") is the reconstructed name or epithet of a hypothetical Common Germanic love goddess, the most prominent female member of the *Ansiwiz (gods), and often identified as the spouse of the chief god, *Wōdanaz (Woden-Odin).

Perchtenlaufen is a folk custom found in the Tyrol region of Central Europe. Occurring on set occasions, the ceremony involves two groups of locals fighting against one another, using wooden canes and sticks. Both groups are masked, one as 'beautiful' and the other as 'ugly' Perchte.

The Krampus is a horned anthropomorphic figure who, in the Central and Eastern Alpine folkloric tradition, is said to accompany Saint Nicholas on visits to children during the night of 5 December (Krampusnacht; “Krampus Night”), immediately before the Feast of St. Nicholas on 6 December. In this tradition, Saint Nicholas rewards well-behaved children with small gifts, while Krampus punishes badly-behaved ones with birch rods.

![Peruchty in Hrdly [cs], Kingdom of Bohemia, 1910 Masopust drzime 10.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/03/Masopust_dr%C5%BE%C3%ADme_10.jpg/260px-Masopust_dr%C5%BE%C3%ADme_10.jpg)