Quechua, also called Runasimi in Southern Quechua, is an indigenous language family that originated in central Peru and thereafter spread to other countries of the Andes. Derived from a common ancestral "Proto-Quechua" language, it is today the most widely spoken pre-Columbian language family of the Americas, with the number of speakers estimated at 8–10 million speakers in 2004, and just under 7 million from the most recent census data available up to 2011. Approximately 13.9% of Peruvians speak a Quechua language.

The different varieties of the Spanish language spoken in the Americas are distinct from each other as well as from those varieties spoken in the Iberian peninsula, collectively known as Peninsular Spanish and Spanish spoken elsewhere, such as in Africa and Asia. There is great diversity among the various Latin American vernaculars, and there are no traits shared by all of them which are not also in existence in one or more of the variants of Spanish used in Spain. A Latin American "standard" does, however, vary from the Castilian "standard" register used in television and notably the dubbing industry. Of the more than 498 million people who speak Spanish as their native language, more than 455 million are in Latin America, the United States and Canada in 2022. The total amount of native and non-native speakers of Spanish as of October 2022 exceeds 595 million.

The Andalusian dialects of Spanish are spoken in Andalusia, Ceuta, Melilla, and Gibraltar. They include perhaps the most distinct of the southern variants of peninsular Spanish, differing in many respects from northern varieties in a number of phonological, morphological and lexical features. Many of these are innovations which, spreading from Andalusia, failed to reach the higher strata of Toledo and Madrid speech and become part of the Peninsular norm of standard Spanish. Andalusian Spanish has historically been stigmatized at a national level, though this appears to have changed in recent decades, and there is evidence that the speech of Seville or the norma sevillana enjoys high prestige within Western Andalusia.

Aymara is an Aymaran language spoken by the Aymara people of the Bolivian Andes. It is one of only a handful of Native American languages with over one million speakers. Aymara, along with Spanish and Quechua, is an official language in Bolivia and Peru. It is also spoken, to a much lesser extent, by some communities in northern Chile, where it is a recognized minority language.

Some of the regional varieties of the Spanish language are quite divergent from one another, especially in pronunciation and vocabulary, and less so in grammar.

This article is about the phonology and phonetics of the Spanish language. Unless otherwise noted, statements refer to Castilian Spanish, the standard dialect used in Spain on radio and television. For historical development of the sound system, see History of Spanish. For details of geographical variation, see Spanish dialects and varieties.

Rioplatense Spanish, also known as Rioplatense Castilian, River Plate Spanish, or Argentine Spanish, is a variety of Spanish originating in and around the Río de la Plata Basin, and now spoken throughout most of Argentina and Uruguay. It is the most prominent dialect to employ voseo in both speech and writing. Many features of Rioplatense are also shared with the varieties spoken in south and eastern Bolivia, and Paraguay. This dialect is often spoken with an intonation resembling that of the Neapolitan language of Southern Italy, but there are exceptions.

Yeísmo is a distinctive feature of certain dialects of the Spanish language, characterized by the loss of the traditional palatal lateral approximant phoneme and its merger into the phoneme. It is an example of delateralization.

Chilean Spanish is any of several varieties of the Spanish language spoken in most of Chile. Chilean Spanish dialects have distinctive pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, and slang usages that differ from those of Standard Spanish. Formal Spanish in Chile has recently incorporated an increasing number of colloquial elements.

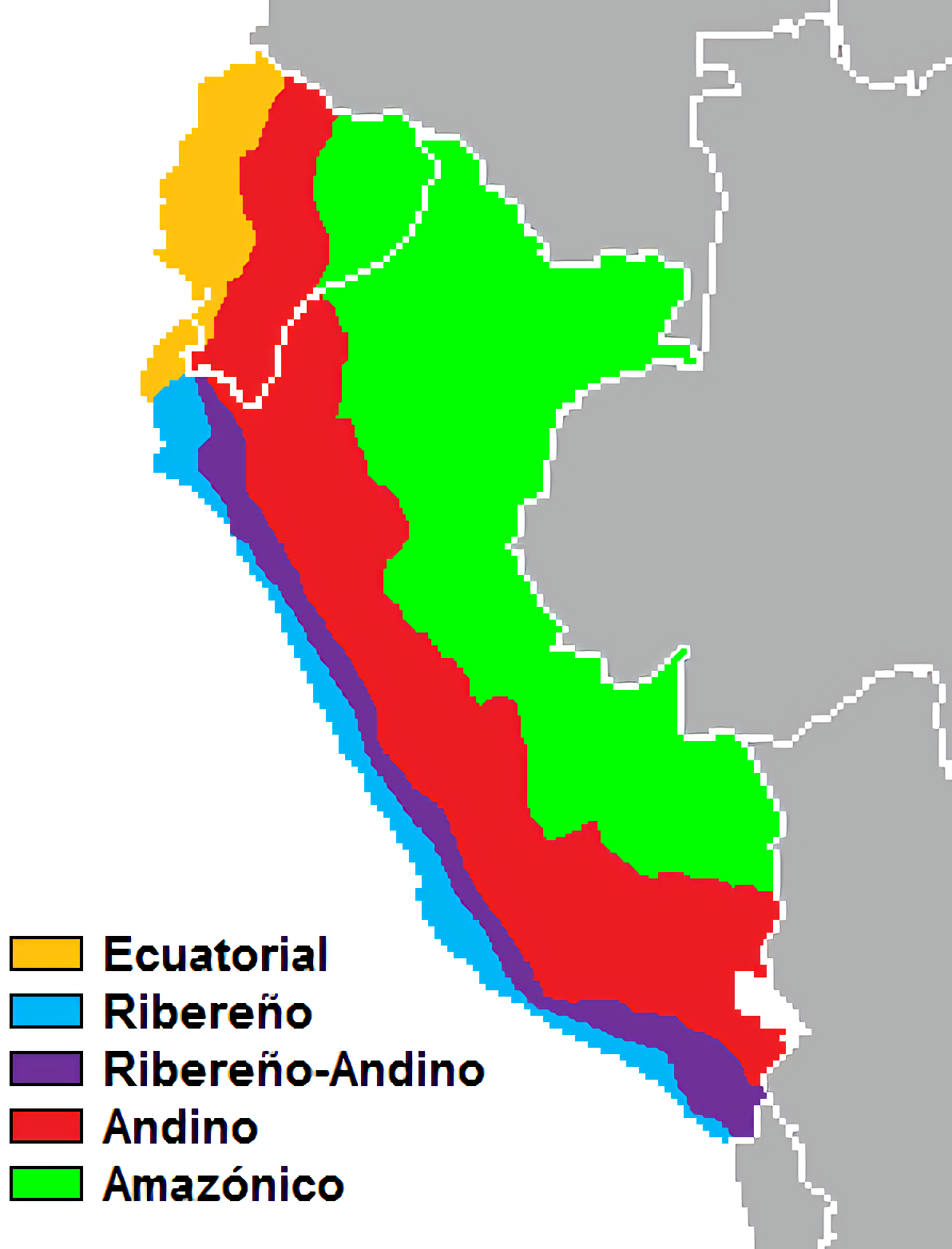

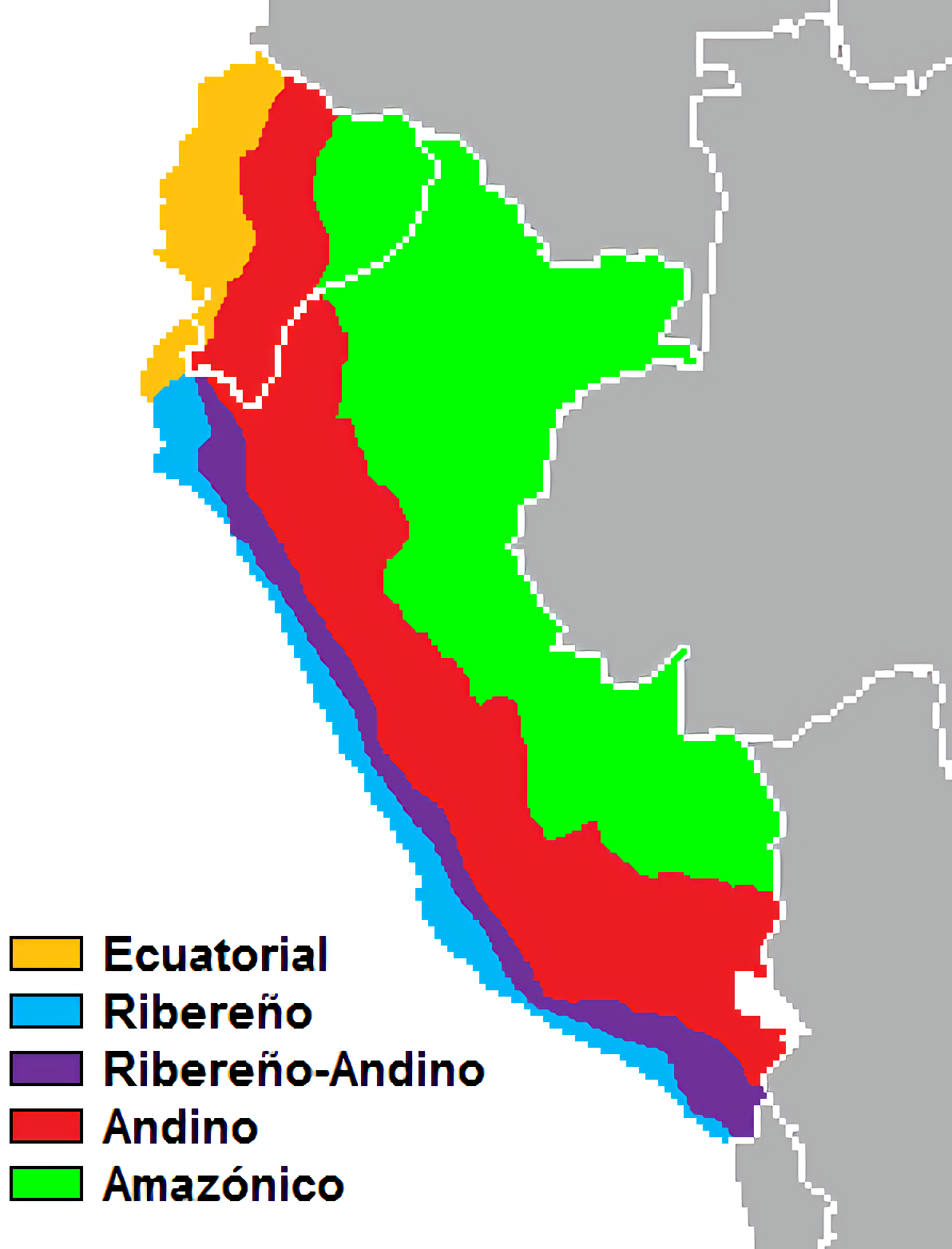

Peruvian Ribereño Spanish or Peruvian Coastal Spanish is the form of the Spanish language spoken in the coastal region of Peru. The Spanish spoken in Coastal Peru has four characteristic forms today: the original one, that of the inhabitants of Lima near the Pacific coast and parts south ; the inland immigrant sociolect ; the Northern, in Trujillo, Chiclayo or Piura; and the Southern. The majority of Peruvians speak Peruvian Coast Spanish, as Peruvian Coast Spanish is the standard dialect of Spanish in Peru.

Southern Quechua, or simply Quechua, is the most widely spoken of the major regional groupings of mutually intelligible dialects within the Quechua language family, with about 6.9 million speakers. It is also the most widely spoken indigenous language in the Americas. The term Southern Quechua refers to the Quechuan varieties spoken in regions of the Andes south of a line roughly east–west between the cities of Huancayo and Huancavelica in central Peru. It includes the Quechua varieties spoken in the regions of Ayacucho, Cusco and Puno in Peru, in much of Bolivia and parts of north-west Argentina. The most widely spoken varieties are Cusco, Ayacucho, Puno (Collao), and South Bolivian.

Cuzco Quechua is a dialect of Southern Quechua spoken in Cuzco and the Cuzco Region of Peru.

The High Academy of the Quechua Language, or AMLQ, is a Peruvian organization dedicated to the teaching, promotion, and dissemination of the Quechua language.

Arabela is a nearly extinct indigenous American language of the Zaparoan family spoken in two Peruvian villages in tropical forest along the Napo tributary of the Arabela river.

Colombian Spanish is a grouping of the varieties of Spanish spoken in Colombia. The term is of more geographical than linguistic relevance, since the dialects spoken in the various regions of Colombia are quite diverse. The speech of the northern coastal area tends to exhibit phonological innovations typical of Caribbean Spanish, while highland varieties have been historically more conservative. The Caro and Cuervo Institute in Bogotá is the main institution in Colombia to promote the scholarly study of the language and literature of both Colombia and the rest of Spanish America. The educated speech of Bogotá, a generally conservative variety of Spanish, has high popular prestige among Spanish-speakers throughout the Americas.

Panamanian Spanish is the Spanish language as spoken in the country of Panama. Despite Panama's location in Central America, Panamanian Spanish is considered a Caribbean variety.

Andean Spanish is a dialect of Spanish spoken in the central Andes, from southern Colombia, with influence as far south as northern Chile and Northwestern Argentina, passing through Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. While similar to other Spanish dialects, Andean Spanish shows influence from Quechua, Aymara, and other indigenous languages, due to prolonged and intense language contact. This influence is especially strong in rural areas.

Spanish is the most-widely spoken language in Ecuador, though great variations are present depending on several factors, the most important one being the geographical region where it is spoken. The three main regional variants are:

North Junín Quechua is a language dialect of Quechua spoken throughout the Andean highlands of the Northern Junín and Tarma Provinces of Perú. Dialects under North Junín Quechua include Tarma Quechua spoken in Tarma Province and the subdialect San Pedros de Cajas Quechua. North Junín Quechua belongs to the Yaru Quechua dialect cluster under the Quechua I dialects. Initially spoken by Huancas and neighboring native people, Quechua's Junín dialect was absorbed by the Inca Empire in 1460 but relatively unaffected by the Southern Cuzco dialect. The Inca Empire had to defeat stiff resistance by the Huanca people.

Bolivian Spanish is the variety of Spanish spoken by the majority of the population in Bolivia, either as a mother tongue or as a second language. Within the Spanish of Bolivia there are different regional varieties. In the border areas, Bolivia shares dialectal features with the neighboring countries.