Albinism is a congenital condition characterized in humans by the partial or complete absence of pigment in the skin, hair and eyes. Albinism is associated with a number of vision defects, such as photophobia, nystagmus, and amblyopia. Lack of skin pigmentation makes for more susceptibility to sunburn and skin cancers. In rare cases such as Chédiak–Higashi syndrome, albinism may be associated with deficiencies in the transportation of melanin granules. This also affects essential granules present in immune cells, leading to increased susceptibility to infection.

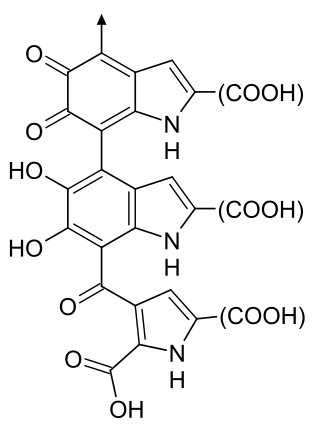

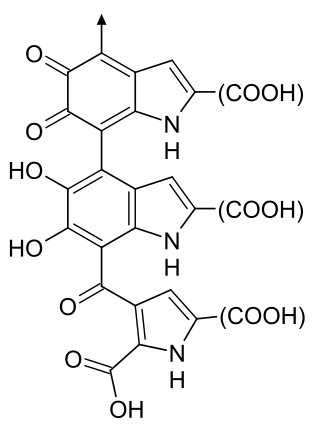

Melanin consist of oligomers or polymers arranged in a disordered manner which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes. They have been described as "among the last remaining biological frontiers with the unknown".

The Eurasian teal, common teal, or Eurasian green-winged teal is a common and widespread duck that breeds in temperate Eurosiberia and migrates south in winter. The Eurasian teal is often called simply the teal due to being the only one of these small dabbling ducks in much of its range. The bird gives its name to the blue-green colour teal.

The superb fairywren is a passerine bird in the Australasian wren family, Maluridae, and is common and familiar across south-eastern Australia. It is a sedentary and territorial species, also exhibiting a high degree of sexual dimorphism; the male in breeding plumage has a striking bright blue forehead, ear coverts, mantle, and tail, with a black mask and black or dark blue throat. Non-breeding males, females and juveniles are predominantly grey-brown in colour; this gave the early impression that males were polygamous, as all dull-coloured birds were taken for females. Six subspecies groups are recognized: three larger and darker forms from Tasmania, Flinders and King Island respectively, and three smaller and paler forms from mainland Australia and Kangaroo Island.

The variegated fairywren is a fairywren that lives in eastern Australia. As a species that exhibits sexual dimorphism, the brightly coloured breeding male has chestnut shoulders and azure crown and ear coverts, while non-breeding males, females and juveniles have predominantly grey-brown plumage, although females of two subspecies have mainly blue-grey plumage.

The science of budgerigar color genetics deals with the heredity of mutations which cause color variation in the feathers of the species known scientifically as Melopsittacus undulatus. Birds of this species are commonly known by the terms 'budgerigar', or informally just 'budgie'.

Gamebird hybrids are the result of crossing species of game birds, including ducks, with each other and with domestic poultry. These hybrid species may sometimes occur naturally in the wild or more commonly through the deliberate or inadvertent intervention of humans.

The splendid fairywren is a passerine bird in the Australasian wren family, Maluridae. It is also known simply as the splendid wren or more colloquially in Western Australia as the blue wren. The splendid fairywren is found across much of the Australian continent from central-western New South Wales and southwestern Queensland over to coastal Western Australia. It inhabits predominantly arid and semi-arid regions. Exhibiting a high degree of sexual dimorphism, the male in breeding plumage is a small, long-tailed bird of predominantly bright blue and black colouration. Non-breeding males, females and juveniles are predominantly grey-brown in colour; this gave the early impression that males were polygamous as all dull-coloured birds were taken for females. It comprises several similar all-blue and black subspecies that were originally considered separate species.

The red-winged fairywren is a species of passerine bird in the Australasian wren family, Maluridae. It is non-migratory and endemic to the southwestern corner of Western Australia. Exhibiting a high degree of sexual dimorphism, the male adopts a brilliantly coloured breeding plumage, with an iridescent silvery-blue crown, ear coverts and upper back, red shoulders, contrasting with a black throat, grey-brown tail and wings and pale underparts. Non-breeding males, females and juveniles have predominantly grey-brown plumage, though males may bear isolated blue and black feathers. No separate subspecies are recognised. Similar in appearance and closely related to the variegated fairywren and the blue-breasted fairywren, it is regarded as a separate species as no intermediate forms have been recorded where their ranges overlap. Though the red-winged fairywren is locally common, there is evidence of a decline in numbers.

The white-winged fairywren is a species of passerine bird in the Australasian wren family, Maluridae. It lives in the drier parts of Central Australia; from central Queensland and South Australia across to Western Australia. Like other fairywrens, this species displays marked sexual dimorphism and one or more males of a social group grow brightly coloured plumage during the breeding season. The female is sandy-brown with light-blue tail feathers; it is smaller than the male, which, in breeding plumage, has a bright-blue body, black bill, and white wings. Younger sexually mature males are almost indistinguishable from females and are often the breeding males. In spring and summer, a troop of white-winged fairywrens has a brightly coloured older male accompanied by small, inconspicuous brown birds, many of which are also male. Three subspecies are recognised. Apart from the mainland subspecies, one is found on Dirk Hartog Island, and another on Barrow Island off the coast of Western Australia. Males from these islands have black rather than blue breeding plumage.

The red-backed fairywren is a species of passerine bird in the Australasian wren family, Maluridae. It is endemic to Australia and can be found near rivers and coastal areas along the northern and eastern coastlines from the Kimberley in the northwest to the Hunter Region in New South Wales. The male adopts a striking breeding plumage, with a black head, upperparts and tail, and a brightly coloured red back and brown wings. The female has brownish upperparts and paler underparts. The male in eclipse plumage and the juvenile resemble the female. Some males remain in non-breeding plumage while breeding. Two subspecies are recognised; the nominate M. m.melanocephalus of eastern Australia has a longer tail and orange back, and the short-tailed M. m. cruentatus from northern Australia has a redder back.

The genetic basis of coat colour in the Labrador Retriever has been found to depend on several distinct genes. The interplay among these genes is used as an example of epistasis.

The science of cockatiel colour genetics deals with the heredity of colour variation in the feathers of cockatiels, Nymphicus hollandicus. Colour mutations are a natural but very rare phenomenon that occur in either captivity or the wild. About fifteen primary colour mutations have been established in the species which enable the production of many different combinations. Note that this article is heavily based on the captive or companion cockatiel rather than the wild cockatiel species.

Amelanism is a pigmentation abnormality characterized by the lack of pigments called melanins, commonly associated with a genetic loss of tyrosinase function. Amelanism can affect fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals including humans. The appearance of an amelanistic animal depends on the remaining non-melanin pigments. The opposite of amelanism is melanism, a higher percentage of melanin.

Lavender or self-blue refers to a plumage color pattern in the chicken characterized by a uniform, pale bluish grey color across all feathers. The distinctive color is caused by the action of an autosomal recessive gene, commonly designated as "lav", which reduces the expression of eumelanin and phaeomelanin so that black areas of the plumage appear pale grey instead, and red areas appear a pale buff.

Solid black plumage color refers to a plumage pattern in chickens characterized by a uniform, black color across all feathers. There are chicken breeds where the typical plumage color is black, such as Australorp, Sumatra, White-Faced Black Spanish, Jersey Giant and others. And there are many other breeds having different color varieties, which also have an extended black variety, such as Leghorn, Minorca, Wyandotte, Orpington, Langshan and others.

In poultry standards, solid white is coloration of plumage in chickens characterized by a uniform pure white color across all feathers, which is not generally associated with depigmentation in any other part of the body.

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and reddish pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albinos.

Dogs have a wide range of coat colors, patterns, textures and lengths. Dog coat color is governed by how genes are passed from dogs to their puppies and how those genes are expressed in each dog. Dogs have about 19,000 genes in their genome but only a handful affect the physical variations in their coats. Most genes come in pairs, one being from the dog's mother and one being from its father. Genes of interest have more than one expression of an allele. Usually only one, or a small number of alleles exist for each gene. In any one gene locus a dog will either be homozygous where the gene is made of two identical alleles or heterozygous where the gene is made of two different alleles.

The purple-backed fairywren is a fairywren that is native to Australia. Described by Alfred John North in 1901, it has four recognised subspecies. In a species that exhibits sexual dimorphism, the brightly coloured breeding male has chestnut shoulders and azure crown and ear coverts, while non-breeding males, females and juveniles have predominantly grey-brown plumage, although females of two subspecies have mainly blue-grey plumage. Distributed over much of the Australian continent, the purple-backed fairywren is found in scrubland with plenty of vegetation providing dense cover.