Related Research Articles

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four million people died from violence, famine or diseases which were directly caused by the conflict; additionally, the conflict severely damaged the power of the French monarchy. The fighting ended in 1598 when Henry of Navarre, who had converted to Catholicism in 1593, was proclaimed Henry IV of France and issued the Edict of Nantes, which granted substantial rights and freedoms to the Huguenots. However, the Catholics continued to have a hostile opinion of Protestants in general and they also continued to have a hostile opinion of him as a person, and his assassination in 1610 triggered a fresh round of Huguenot rebellions in the 1620s.

Anne, Duke of Montmorency, Honorary Knight of the Garter was a French soldier, statesman and diplomat. He became Marshal of France and Constable of France and served five kings.

Henri I de Bourbon, Prince of Condé was a French Prince du Sang and Huguenot general like his more prominent father, Louis I, Prince of Condé.

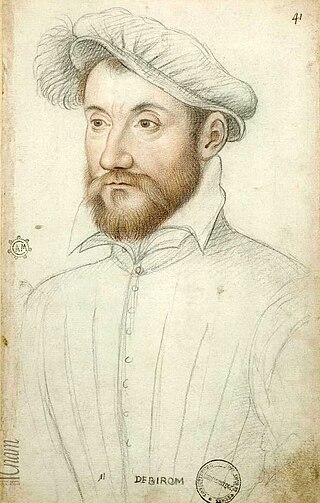

Armand de Gontaut, baron de Biron was a soldier, diplomat and Marshal of France. Beginning his service during the Italian Wars, Biron served in Italy under Marshal Brissac and Guise in 1557 before rising to command his own cavalry regiment. Returning to France with the Peace of Cateau-Cambresis he took up his duties in Guyenne, where he observed the deteriorating religious situation that was soon to devolve into the French Wars of Religion. He fought at the Battle of Dreux in the first civil war. In the peace that followed he attempted to enforce the terms on the rebellious governorship of Provence.

Jacques de Savoie, duc de Nemours was a French military commander, governor and Prince Étranger. Having inherited his titles at a young age, Nemours fought for king Henri II during the latter Italian Wars, seeing action at the siege of Metz and the stunning victories of Renty and Calais in 1554 and 1558. Already a commander of French infantry, he received promotion to commander of the light cavalry after the capture of Calais in 1558. A year prior he had accompanied François, Duke of Guise on his entry into Italy, as much for the purpose of campaigning as to escape the king's cousin Antoine of Navarre who was threatening to kill him for his extra-marital pursuit of Navarre's cousin.

Jacques d'Albon, Seigneur de Saint-André was a French governor, Marshal, and favourite of Henri II. He began his career as a confident of the dauphin during the reign of François I, reared with the prince under the governorship of his father at court. In 1547 at the advent of Henri's reign he was appointed as his father's deputy, serving as lieutenant general for the Lyonnais. Concurrently he entered the king's conseil privé and was made a Marshal and Grand Chamberlain.

The Battle of Saint-Denis was fought on 10 November 1567 between a Royalist army and Huguenot rebels during the second of the French Wars of Religion. Although their 74 year old commander, Anne de Montmorency, was killed in the fighting, the Royalists forced the rebels to withdraw, allowing them to claim victory.

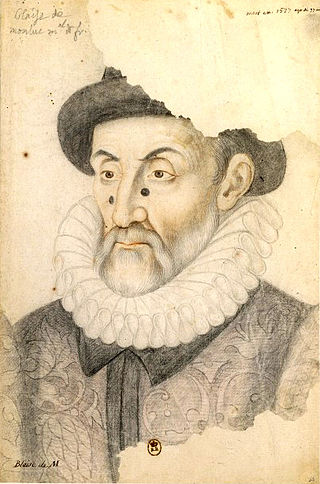

Blaise de Monluc, also known as Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Monluc, was a professional soldier whose career began in 1521 and reached the rank of marshal of France in 1574. Written between 1570 and 1576, an account of his life titled Commentaires de Messire Blaise de Monluc was published in 1592, and remains an important historical source for 16th century warfare.

Louis de Clermont, seigneur de Bussy d'Amboise (1549–1579) was a noble, military commander and governor during the French Wars of Religion. His great-uncle was Georges d'Amboise, who was the primary adviser to king Louis XII, as a result he inherited a range of lands from his father. Entering politics in 1568, he led a company of men-at-arms in the third civil war. In 1574 he fought in the fourth civil war in Normandy and was rewarded for his service with the office of maître de camp and three more companies.

The Peace of Longjumeau was signed on 23 March 1568 by Charles IX of France and Catherine de' Medici. The edict brought to an end the brief second French Wars of Religion with terms that largely confirmed those of the prior edict of Amboise. Unlike the previous edict it would not be sent to the Parlements to examine prior to its publication, due to what the crown had felt was obstructionism the last time. The edict would not however last, and it would be overturned later in the year, being replaced by the Edict of Saint-Maur which outlawed Protestantism at the beginning of the third war of religion.

Louis de Gonzague, Duke of Nevers was a soldier, governor and statesman during the French Wars of Religion. Of Italian extraction, his father and brother were dukes of Mantua. He came to France in 1549, and fought for Henri II of France during the latter wars of religion, getting himself captured during the battle of Saint Quentin. Due to his Italian heritage he was seen as a useful figure to have as governor of French Piedmont, a post he would hold until Henri III ceded the territory in 1574. In 1565 his patron, Catherine de Medici secured for him a marriage with the key heiress Henriette de Clèves, elevating him to duke of Nevers and count of Rethelois. He fought for the crown through the early wars of religion, receiving a bad injury in the third war. At this time he formed a close bond with the young Anjou, future king Henri III, a bond that would last until the kings death.

Anne de Batarnay de Joyeuse, Baron d'Arques, Vicomte then Duke of Joyeuse was a royal favourite and active participant in the French Wars of Religion.

Louis de Bourbon, Duc de Montpensier was the second Duke of Montpensier, a French Prince of the Blood, military commander and governor. He began his military career during the Italian Wars, and in 1557 was captured after the disastrous battle of Saint-Quentin. His liberty restored he found himself courted by the new regime as it sought to steady itself and isolate its opponents in the wake of the Conspiracy of Amboise. At this time Montpensier supported liberalising religious reform, as typified by the Edict of Amboise he was present for the creation of.

Albert de Gondi, duc de Retz seigneur du Perron, comte, then marquis de Belle-Isle (1573), duc de Retz, was a marshal of France and a member of the Gondi family. Beginning his career during the Italian Wars he fought at the Battle of Renty in 1554, and in many of the campaigns into Italy in the following years, before returning to France for the disastrous battle of Saint-Quentin and battle of Gravelines both of which saw the French army savaged.

The siege of Montpellier was a siege of the Huguenot city of Montpellier by the Catholic forces of Louis XIII of France, from August to October 1622. It was part of the Huguenot rebellions.

Honorat de Savoie, marquis of Villars was a marshal of France and admiral of France. Born into a cadet branch of the house of Savoy, he fought for first Francis I, and then Henri II during the Italian Wars. This included fighting at Hesdin and the battle of Saint-Quentin. During this period he also conducted diplomacy for the French court, and was involved in the negotiations that brought an end to the Italian Wars. Subsequently he received the office of lieutenant-general of Languedoc, in which he supressed Huguenots for several years before resigning the commission in 1562.

Artus de Cossé-Brissac (1512–1582), lord of Gonnor and Comte de Secondigny, was a Marshal of France, an office he was elevated to in 1567. He served to administer the armies finances during the first of the French Wars of Religion and would lead the royal army in its pursuit of the Prince of Condé during the second civil war. His failure to catch the army led to his dismissal from overall royal command. During the third civil war he would again lead troops, beating a small Protestant force, before being defeated in the final days of the war at Arney-le-Duc. His long history of Politique leanings would push him into the orbit of the Malcontents for which he would be arrested in 1574. In 1576 he would be released and restored to favour before he died in 1582.

Guillaume de Joyeuse (1520–1592) was a French military commander during the French Wars of Religion. Originally destined for the church, he assumed the office of vicomte de Joyeuse upon the death of his elder brother in 1554. He was subsequently appointed at lieutenant-general of Languedoc, under the governor Antoine de Crussol. In this capacity he established himself as a harsh persecutor of Protestantism. When the civil wars broke out in 1562 he assumed his military responsibilities, regularly fighting with the viscomtes de Languedoc throughout the early civil wars. He achieved a notable victory against them in 1568 on the field of Montfran. He did not spread the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew into the territory he controlled and remained loyal to the crown during the fifth civil war, fighting with the Malcontents. In 1582 he was elevated to Marshal of France by Henri III. He found himself increasingly drawn to the Catholic League (France) after its formal formation and when Henri III was assassinated in 1589 he fought against Navarre for Charles, Duke of Mayenne and the league. He died in 1592.

Jacques II de Goyon seigneur de Matignon (1525-1598) was a governor and Marshal of France. Coming from a prominent Norman family, he assumed the role of Lieutenant-General of lower Normandy. In this position he came into conflict with the Protestant governor of Normandy Bouillon. During the first civil war Matignon would come into conflict with the governor, who occupied a third individual position between the crown and the rebels as he felt his authority eroded. In 1574 the governorship of Normandy which had become vacant was split into three separate offices between Matignon, Moy and Carrouges. He would hold the governorship until it was reunited in 1583 for Henri III's favourite Anne de Joyeuse

Guillaume de Montmorency, comte de Thoré was a French noble, and military commander during the latter French Wars of Religion. Thoré was among those Catholic nobles who were perceived as soft on Protestantism, and as such during the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew he feared for his life. Shortly after the massacre as France descended back into civil war, Thoré, lacking military experience and keen to prove himself militarily joined the siege of La Rochelle.

References

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 76.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Thompson 1909, p. 497.

- ↑ Thompson 1909, p. 498.

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 34.

- ↑ Knecht 2016, p. 101.

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 35.

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 178.

- ↑ Salmon 1975, p. 203.

- ↑ Knecht 1998, p. 193.

- ↑ Roberts 2013, p. 136.

- ↑ Salmon 1975, p. 210.

- ↑ Knecht 1998, p. 199.