A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus Mammuthus. They lived from the late Miocene epoch into the Holocene about 4,000 years ago, and various species existed in Africa, Europe, Asia, and North America. Mammoths are more closely related to living Asian elephants than African elephants.

Proboscidea is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three species of elephant are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant.

Elephantidae is a family of large, herbivorous proboscidean mammals collectively called elephants and mammoths. These are large terrestrial mammals with a snout modified into a trunk and teeth modified into tusks. Most genera and species in the family are extinct. Only two genera, Loxodonta and Elephas, are living.

Mammutidae is an extinct family of proboscideans belonging to Elephantimorpha. It is best known for the mastodons, which inhabited North America from the Late Miocene until their extinction at beginning of the Holocene, around 11,000 years ago. The earliest fossils of the group are known from the Late Oligocene of Africa, around 24 million years ago, and fossils of the group have also been found across Eurasia. The name "mastodon" derives from Greek, μαστός "nipple" and ὀδούς "tooth", referring to their characteristic teeth.

Elephas is one of two surviving genera in the family of elephants, Elephantidae, with one surviving species, the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus. Several extinct species have been identified as belonging to the genus, extending back to the Pliocene era.

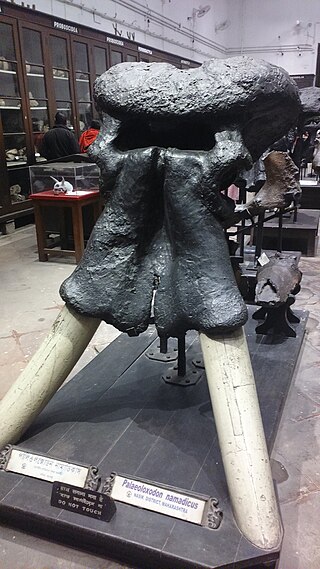

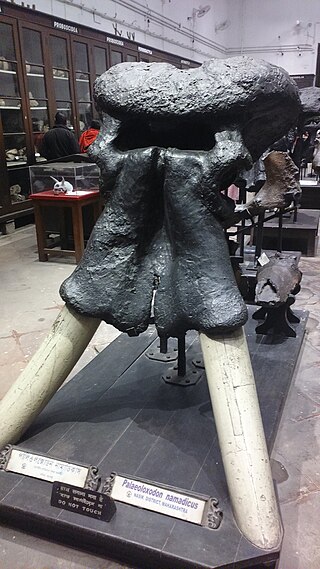

Palaeoloxodon is an extinct genus of elephant. The genus originated in Africa during the Early Pleistocene, and expanded into Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene. The genus contains some of the largest known species of elephants, over 4 metres (13 ft) tall at the shoulders, including the African Palaeoloxodon recki, the European straight-tusked elephant and the South Asian Palaeoloxodon namadicus. P. namadicus has been suggested to be the largest known land mammal by some authors based on extrapolation from fragmentary remains, though these estimates are highly speculative. In contrast, the genus also contains many species of dwarf elephants that evolved via insular dwarfism on islands in the Mediterranean, some only 1 metre (3.3 ft) in height, making them the smallest elephants known. The genus has a long and complex taxonomic history, and at various times, it has been considered to belong to Loxodonta or Elephas, but today is usually considered a valid and separate genus in its own right.

Gomphotheres are an extinct group of proboscideans related to modern elephants. They were widespread across Afro-Eurasia and North America during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs and dispersed into South America during the Pleistocene as part of the Great American Interchange. Gomphotheres are a paraphyletic group that is ancestral to Elephantidae, which contains modern elephants, as well as Stegodontidae. While most famous forms such as Gomphotherium had long lower jaws with tusks, which is the ancestral condition for the group, some later members developed shortened (brevirostrine) lower jaws with either vestigial or no lower tusks, looking very similar to modern elephants, an example of parallel evolution, which outlasted the long-jawed gomphotheres. By the end of the Early Pleistocene, gomphotheres became extinct in Afro-Eurasia, with the last two genera, Cuvieronius ranging from southern North America to western South America, and Notiomastodon having a wide range over most of South America until the end of the Pleistocene around 12,000 years ago, when they became extinct following the arrival of humans.

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephants are an example of insular dwarfism, the phenomenon whereby large terrestrial vertebrates that colonize islands evolve dwarf forms, a phenomenon attributed to adaptation to resource-poor environments and lack of predation and competition.

Palaeoloxodon recki, often known by the synonym Elephas recki is an extinct species of elephant native to Africa and West Asia from the Pliocene or Early Pleistocene to the Middle Pleistocene. During most of its existence, the species represented the dominant elephant species in East Africa. The species is divided into five roughly chronologically successive subspecies. While the type and latest subspecies P. recki recki as well as the preceding P. recki ileretensis are widely accepted to be closely related to Eurasian Palaeoloxodon, the relationships of the other, chronologically earlier subspecies to P. recki recki and P. recki ileretensis are uncertain, with it being suggested they are unrelated and should be elevated to separate species.

Anancus is an extinct genus of "tetralophodont gomphothere" native to Afro-Eurasia, that lived from the Tortonian stage of the late Miocene until its extinction during the Early Pleistocene, roughly from 8.5–2 million years ago.

Sinomastodon is an extinct gomphothere genus known from the Late Miocene to Early Pleistocene of Asia, including China, Japan, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia and probably Kashmir.

Palaeoloxodon namadicus is an extinct species of prehistoric elephant known from the early Middle to Late Pleistocene of the Indian subcontinent, and possibly also elsewhere in Asia. The species grew larger than any living elephant, and some authors have suggested it to have been the largest known land mammal based on extrapolation from fragmentary remains, though these estimates are speculative.

Stegolophodon is an extinct genus of stegodontid proboscideans. It lived during the Miocene epoch in Asia. The earliest fossils are known from the Early Miocene, with one of the oldest fossils being from Japan, estimated to be 17.3 million years old. It is suggested to be the ancestor of Stegodon, and transitional fossils between the two genera known from the Late Miocene of Southeast Asia and Yunnan in South China. Like modern elephants, Stegolophodon developed proal jaw movement, where the lower jaw moves in a back-to-front motion, rather than the oblique chewing motion used by earlier proboscideans, with this development already present by 17.3 million years ago. Members of the genus generally have tetralophodont molars, and retain tusks on the lower jaw. The upper tusks have an enamel band.

Elephas hysudricus is an extinct elephant species known from the Pleistocene of Asia. It is thought to be ancestral to the living Asian elephant, from which it is distinguished by the molar teeth having a lower crown height and a lower lamellae number. Remains of the species are primarily known from the Indian subcontinent, with the most important remains coming from the Siwalik Hills. The oldest remains of the species in the Siwaliks are placed at around 2.6 million year ago at the beginning of the Early Pleistocene, with the youngest dates in the Siwaliks during the Middle Pleistocene around 0.6 million years ago, though it likely persisted on the subcontinent later than this based on remains found elsewhere. Remains likely attributable to the species are also known from the Levant in Israel and Jordan, dating to the late Middle Pleistocene, likely sometime between 500-100,000 years ago. Isotopic analysis of specimens from the Indian subcontinent suggests that early members of the species were likely primarily grazers, but shifted towards mixed feeding after the arrival of the substantially larger elephant species Palaeoloxodon namadicus to the region. It is suggested to be closely related and possibly ancestral to the extinct Elephas hysudrindicus from the Pleistocene of Java in Indonesia.

Stegodontidae is an extinct family of proboscideans from Africa and Asia from the Early Miocene to the Late Pleistocene. It contains two genera, the earlier Stegolophodon, known from the Miocene of Asia and the later Stegodon, from the Late Miocene to Late Pleistocene of Africa and Asia which is thought to have evolved from the former. The group is noted for their plate-like lophs on their teeth, which are similar to elephants and different from those of other extinct proboscideans like gomphotheres and mammutids, with both groups having a proal jaw movement utilizing forward strokes of the lower jaw. These similarities with modern elephants were probably convergently evolved. Like elephantids, stegodontids are thought to have evolved from gomphothere ancestors.

Palaeoloxodon naumanni, occasionally called Naumann's elephant, is an extinct species belonging to the genus Palaeoloxodon found in the Japanese archipelago during the Middle to Late Pleistocene around 330,000 to 24,000 years ago. It is named after Heinrich Edmund Naumann who discovered the first fossils at Yokosuka, Kanagawa, Japan. Fossils attributed to P. naumanni are also known from China and Korea, though the status of these specimens is unresolved, and some authors regard them as belonging to separate species.

Elephas hysudrindicus, commonly known also as the Blora elephant in Indonesia, is a species of extinct elephant from the Pleistocene of Java. It is anatomically distinct from the Asian elephant, the last remaining species of elephant under the genus Elephas. The species existed from around the end of the Early Pleistocene until the end of the Middle Pleistocene, when it was replaced by the modern Asian elephant, coexisting alongside fellow proboscidean Stegodon trigonocephalus, as well archaic humans belonging to the species Homo erectus.

Stegodon aurorae, also known as the Akebono elephant, is a species of fossil elephantoid known from Early Pleistocene Japan and Taiwan.

Elephas planifrons is an extinct species of elephant, known from the Late Pliocene-Early Pleistocene of the Indian subcontinent.

Stegoloxodon is an extinct genus of dwarf elephant known from the Early Pleistocene of Indonesia. It contains two species, S. indonesicus from Java, and S. celebensis from Sulawesi. Its relationship with other elephants is uncertain.