A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus Mammuthus. They lived from the late Miocene epoch into the Holocene about 4,000 years ago, and various species existed in Africa, Europe, Asia, and North America. Mammoths are more closely related to living Asian elephants than African elephants.

Elephantidae is a family of large, herbivorous proboscidean mammals collectively called elephants and mammoths. These are large terrestrial mammals with a snout modified into a trunk and teeth modified into tusks. Most genera and species in the family are extinct. Only two genera, Loxodonta and Elephas, are living.

Elephas is one of two surviving genera in the family of elephants, Elephantidae, with one surviving species, the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus. Several extinct species have been identified as belonging to the genus, extending back to the Pliocene era.

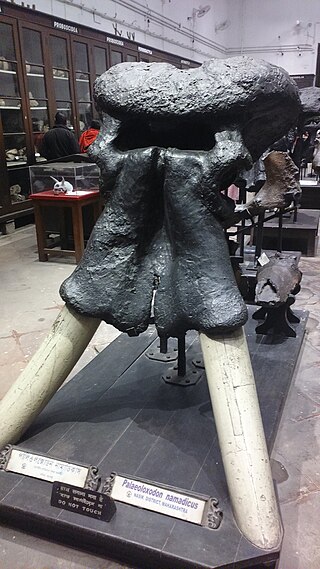

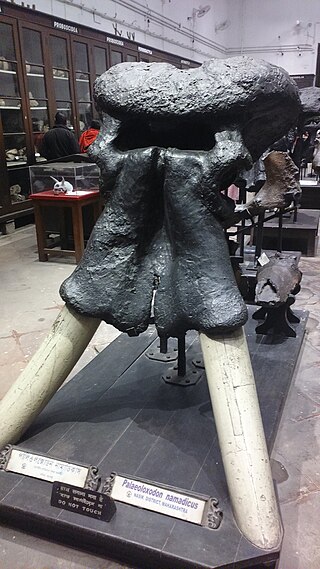

Palaeoloxodon is an extinct genus of elephant. The genus originated in Africa during the Early Pleistocene, and expanded into Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene. The genus contains some of the largest known species of elephants, over 4 metres (13 ft) tall at the shoulders, including the African Palaeoloxodon recki, the European straight-tusked elephant and the South Asian Palaeoloxodon namadicus. P. namadicus has been suggested to be the largest known land mammal by some authors based on extrapolation from fragmentary remains, though these estimates are highly speculative. In contrast, the genus also contains many species of dwarf elephants that evolved via insular dwarfism on islands in the Mediterranean, some only 1 metre (3.3 ft) in height, making them the smallest elephants known. The genus has a long and complex taxonomic history, and at various times, it has been considered to belong to Loxodonta or Elephas, but today is usually considered a valid and separate genus in its own right.

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephants are an example of insular dwarfism, the phenomenon whereby large terrestrial vertebrates that colonize islands evolve dwarf forms, a phenomenon attributed to adaptation to resource-poor environments and lack of predation and competition.

Palaeoloxodon recki, often known by the synonym Elephas recki is an extinct species of elephant native to Africa and West Asia from the Pliocene or Early Pleistocene to the Middle Pleistocene. During most of its existence, the species represented the dominant elephant species in East Africa. The species is divided into five roughly chronologically successive subspecies. While the type and latest subspecies P. recki recki as well as the preceding P. recki ileretensis are widely accepted to be closely related to Eurasian Palaeoloxodon, the relationships of the other, chronologically earlier subspecies to P. recki recki and P. recki ileretensis are uncertain, with it being suggested they are unrelated and should be elevated to separate species.

The Chibanian, widely known as the Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. The Chibanian name was officially ratified in January 2020. It is currently estimated to span the time between 0.770 Ma and 0.126 Ma, also expressed as 770–126 ka. It includes the transition in palaeoanthropology from the Lower to the Middle Paleolithic over 300 ka.

Anancus is an extinct genus of "tetralophodont gomphothere" native to Afro-Eurasia, that lived from the Tortonian stage of the late Miocene until its extinction during the Early Pleistocene, roughly from 8.5–2 million years ago.

Palaeoloxodon falconeri is an extinct species of dwarf elephant from the Middle Pleistocene of Sicily and Malta. It is amongst the smallest of all dwarf elephants at only 1 metre (3.3 ft) in height. A member of the genus Palaeoloxodon, it derived from a population of the mainland European straight-tusked elephant.

Mammuthus meridionalis, sometimes called the southern mammoth, is an extinct species of mammoth native to Eurasia, including Europe, during the Early Pleistocene, living from around 2.5 million years ago to 800,000 years ago.

Mammuthus trogontherii, sometimes called the steppe mammoth, is an extinct species of mammoth that ranged over most of northern Eurasia during the Early and Middle Pleistocene, approximately 1.7 million-200,000 years ago. One of the largest mammoth species, it evolved in East Asia during the Early Pleistocene, around 1.8 million years ago, before migrating into North America around 1.5 million years ago, and into Europe during the Early/Middle Pleistocene transition, around 1 to 0.7 million years ago. It was the ancestor of the woolly mammoth and Columbian mammoth of the later Pleistocene.

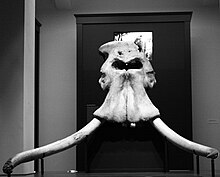

Palaeoloxodon namadicus is an extinct species of prehistoric elephant known from the early Middle to Late Pleistocene of the Indian subcontinent, and possibly also elsewhere in Asia. The species grew larger than any living elephant, and some authors have suggested it to have been the largest known land mammal based on extrapolation from fragmentary remains, though these estimates are speculative.

Mammuthus lamarmorai is a species of dwarf mammoth which lived during the late Middle and Late Pleistocene on the island of Sardinia in the Mediterranean. It has been estimated to have had a shoulder height of around 1.4 metres (4.6 ft). Remains have been found across the western part of the island.

Palaeoloxodon cypriotes is an extinct species of dwarf elephant that inhabited the island of Cyprus during the Late Pleistocene. Remains comprise 44 molars, found in the north of the island, seven molars discovered in the south-east, a single measurable femur and a single tusk among very sparse additional bone and tusk fragments. The molars support derivation from the large straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus). The species is presumably derived from the older, larger P. xylophagou from the late Middle Pleistocene which reached the island presumably during a Pleistocene glacial maximum when low sea levels allowed a low probability sea crossing between Cyprus and Asia Minor. During subsequent periods of isolation the population adapted within the evolutionary mechanisms of insular dwarfism, which the available sequence of molar fossils confirms to a certain extent. The fully developed Palaeoloxodon cypriotes weighed not more than 200 kg (440 lb) and had a height of around 1 m (3.28 ft). The species became extinct around 12,000 years ago, around the time humans first colonised Cyprus.

The woolly mammoth is an extinct species of mammoth that lived from the Middle Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African Mammuthus subplanifrons in the early Pliocene. The woolly mammoth began to diverge from the steppe mammoth about 800,000 years ago in Siberia. Its closest extant relative is the Asian elephant. The Columbian mammoth lived alongside the woolly mammoth in North America, and DNA studies show that the two hybridised with each other.

Palaeoloxodon mnaidriensis is an extinct species of dwarf elephant belonging to the genus Palaeoloxodon, native to the Siculo-Maltese archipelago during the late Middle Pleistocene and Late Pleistocene. It is derived from the European mainland straight-tusked elephant.

Palaeoloxodon naumanni, occasionally called Naumann's elephant, is an extinct species belonging to the genus Palaeoloxodon found in the Japanese archipelago during the Middle to Late Pleistocene around 330,000 to 24,000 years ago. It is named after Heinrich Edmund Naumann who discovered the first fossils at Yokosuka, Kanagawa, Japan. Fossils attributed to P. naumanni are also known from China and Korea, though the status of these specimens is unresolved, and some authors regard them as belonging to separate species.

The narrow-nosed rhinoceros, also known as the steppe rhinoceros is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus Stephanorhinus that lived in western Eurasia, including Europe, as well as North Africa during the Pleistocene. It first appeared in Europe some 600,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene and survived there until at least 34,000 years Before Present.

Bubalus murrensis, also known as European water buffalo, is an extinct buffalo species native to Europe during the Pleistocene epoch.

Palaeoloxodon huaihoensis is an extinct species of elephant belonging to the genus Palaeoloxodon known from the Pleistocene of China.