The Nicaragua Canal, formally the Nicaraguan Canal and Development Project was a proposed shipping route through Nicaragua to connect the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. Scientists were concerned about the project's environmental impact, as Lake Nicaragua is Central America's key freshwater reservoir while the project's viability was questioned by shipping experts and engineers.

The Suez Canal is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The 193.30-kilometre-long (120.11 mi) canal is a key trade route between Europe and Asia.

Malacca Strait is a narrow stretch of water, 500 mi long and from 40 to 155 mi wide, located between the Indonesian island of Sumatra to the southwest and the Malay Peninsula to the northeast, connecting the Andaman Sea with the Singapore Strait and the South China Sea As the main shipping channel between the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, it is one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. It is named after the Phyllanthus emblica, which known by the locals as the Malaka tree, grown in coastal regions alongside the strait.

The Bab-el-Mandeb, the Gate of Grief or the Gate of Tears, is a strait between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa. It connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and by extension the Indian Ocean.

The Sunda Strait is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Ranong is one of Thailand's southern provinces (changwat), on the west coast along the Andaman Sea. It has the fewest inhabitants of all Thai provinces. provinces neighboring Ranong are (clockwise) Chumphon, Surat Thani, and Phang Nga. To the west, it borders Kawthaung, Tanintharyi, Myanmar.

The Kra Isthmus in Thailand is the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula. The western part of the isthmus belongs to Ranong Province and the eastern part to Chumphon Province, both in Southern Thailand. The isthmus is bordered to the west by the Andaman Sea and to the east by the Gulf of Thailand.

A cargo ship or freighter is a merchant ship that carries cargo, goods, and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year, handling the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usually specially designed for the task, often being equipped with cranes and other mechanisms to load and unload, and come in all sizes. Today, they are almost always built of welded steel, and with some exceptions generally have a life expectancy of 25 to 30 years before being scrapped.

In military strategy, a choke point, or sometimes bottleneck, is a geographical feature on land such as a valley, defile or bridge, or maritime passage through a critical waterway such as a strait, which an armed force is forced to pass through in order to reach its objective, sometimes on a substantially narrowed front and therefore greatly decreasing its combat effectiveness by making it harder to bring superior numbers to bear. A choke point can allow a numerically inferior defending force to use the terrain as a force multiplier to thwart or ambush a much larger opponent, as the attacker cannot advance any further without first securing passage through the choke point.

Kyaukphyu is a major town in Rakhine State, in western Myanmar. It is located on the north western corner of Yanbye Island on Combermere Bay, and is 250 miles (400 km) north-west of Yangon. It is the principal town of Kyaukphyu Township and Kyaukphyu District. The town is situated on a superb natural harbor which connects the rice trade between Calcutta and Yangon. The estimated population in 1983 was 19,456 inhabitants. The population of Kyaukphyu's urban area is 20,866 as of 2014, while Kyaukphyu Township's population is 165,352.

The Gwadar Port is situated on the Arabian Sea at Gwadar in Balochistan province of Pakistan and is under the administrative control of the Maritime Secretary of Pakistan and operational control of the China Overseas Port Holding Company. The port features prominently in the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) plan, and is considered to be a link between the Belt and Road Initiative and the Maritime Silk Road projects. It is about 120 kilometres (75 mi) southwest of Turbat, and 170 kilometres (110 mi) to the east of Chabahar Port.

Piracy in the Strait of Malacca has long been a threat to ship owners and the mariners who ply the 900 km-long sea lane. In recent years, coordinated patrols by Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore along with increased security on vessels have sparked a sharp downturn in piracy.

Malaccamax is a naval architecture term for the largest tonnage of ship capable of fitting through the 25-metre-deep (82 ft) Strait of Malacca. Bulk carriers and supertankers have been built to this tonnage, and the term is chosen for very large crude carriers (VLCC). They can transport oil from Arabia to China. A typical Malaccamax tanker can have a maximum length of 333 m (1,093 ft), beam of 60 m (197 ft), draught of 20.5 m (67.3 ft), and tonnage of 300,000 DWT.

The Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC) is the only tri-service theater command of the Indian Armed Forces, based at Port Blair in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a Union Territory of India. It was created in 2001 to safeguard India's strategic interests in Southeast Asia and the Strait of Malacca by increasing rapid deployment of military assets in the region. It provides logistical and administrative support to naval ships which are sent on deployment to East Asia and the Pacific Ocean.

The String of Pearls is a geopolitical hypothesis proposed by United States political researchers in 2004. The term refers to the network of Chinese military and commercial facilities and relationships along its sea lines of communication, which extend from the Chinese mainland to Port Sudan in the Horn of Africa. The sea lines run through several major maritime choke points such as the Strait of Mandeb, the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Lombok Strait as well as other strategic maritime centres in Somalia and the littoral South Asian countries of Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and the Maldives.

Piracy in Indonesia is not only notorious, but according to a survey conducted by the International Maritime Bureau, it was also the country sporting the highest rate of pirate attacks back in 2004, where it subsequently dropped to second place of the world's worst country of pirate attacks in 2008, finishing just behind Nigeria. However, Indonesia is still deemed the country with the world's most dangerous water due to its high piracy rate. With more than half of the world's piracy crimes surrounding the South-East Asia aquatic regions, the turmoil caused by piracy has made the Strait of Malacca a distinct pirate hotspot accounting for most of the attacks in Indonesia, making the ships that sail in this region risky ever since the Europeans arrived. The term 'Piracy in Indonesia' includes both cases of Indonesian pirates hijacking other cargo and tanks, as well as the high rate of practising piracy within the country itself. The Strait of Malacca is also one of the world's busiest shipping routes as it accounts for more than twenty-five percent of the world's barter goods that come mainly from China and Japan. Approximately 50,000 vessels worth of the world's trade employ the strait annually, including oil from the Persian Gulf and manufactured goods to the Middle East and Suez Canal. The success that stems from this trade portal makes the Strait an ideal location for pirate attacks.

The Central Spine Road 2 or Malacca Strait Bridge is a proposed bridge that would connect Telok Gong, near Masjid Tanah, Malacca in Peninsular Malaysia to Rupat Island and Dumai in Sumatra island, Indonesia. The project has been submitted for government approval, and is expected to take 10 years to complete. Once completed, the 48-kilometre-long (30 mi) bridge will be the longest sea-crossing bridge in the world. The project will have two cable-stayed bridges and one suspension bridge, both the longest in the world.

The Istanbul Canal is a project for an artificial sea-level waterway planned by Turkey in East Thrace, connecting the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara, and thus to the Aegean and Mediterranean seas. Istanbul Canal would bisect the current European side of Istanbul and thus form an island between Asia and Europe. The new waterway would bypass the current Bosporus.

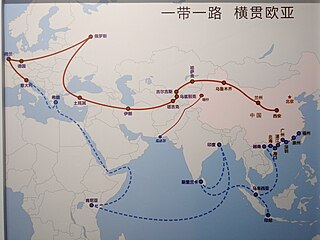

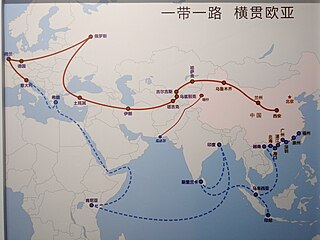

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, commonly just Maritime Silk Road (MSR), is the sea route part of the Belt and Road Initiative which is a Chinese strategic initiative to increase investment and foster collaboration across the historic Silk Road.