Related Research Articles

The Sinhala script, also known as Sinhalese script, is a writing system used by the Sinhalese people and most Sri Lankans in Sri Lanka and elsewhere to write the Sinhala language as well as the liturgical languages Pali and Sanskrit. The Sinhalese Akṣara Mālāva, one of the Brahmic scripts, is a descendant of the Ancient Indian Brahmi script. It is also related to the Grantha script.

Brahmi is a writing system of ancient India that appeared as a fully developed script in the 3rd century BCE. Its descendants, the Brahmic scripts, continue to be used today across Southern and Southeastern Asia.

The Tamil script is an abugida script that is used by Tamils and Tamil speakers in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and elsewhere to write the Tamil language. It is one of the official scripts of the Indian Republic. Certain minority languages such as Saurashtra, Badaga, Irula and Paniya are also written in the Tamil script.

The Indus script, also known as the Harappan script, is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilisation. Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not they constituted a writing system used to record the as-yet unidentified language(s) of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Despite many attempts, the 'script' has not yet been deciphered, but efforts are ongoing. There is no known bilingual inscription to help decipher the script, which shows no significant changes over time. However, some of the syntax varies depending upon location.

Several Dhivehi scripts have been used by Maldivians during their history. The early Dhivehi scripts fell into the abugida category, while the more recent Thaana has characteristics of both an abugida and a true alphabet. An ancient form of Nagari script, as well as the Arabic and Devanagari scripts, have also been extensively used in the Maldives, but with a more restricted function. Latin was official only during a very brief period of the Islands' history.

Tamilakam is the geographical region inhabited by the ancient Tamil people, covering the southernmost region of the Indian subcontinent. Tamilakam covered today's Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, Lakshadweep and southern parts of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Traditional accounts and the Tolkāppiyam referred to these territories as a single cultural area, where Tamil was the natural language and permeated the culture of all its inhabitants. The ancient Tamil country was divided into kingdoms. The best known among them were the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyans and Pallavas. During the Sangam period, Tamil culture began to spread outside Tamilakam. Ancient Tamil settlements were also established in Sri Lanka and the Maldives (Giravarus).

Vatteluttu, popularly romanised as Vattezhuthu, was an alphasyllabic writing system of south India and Sri Lanka used for writing the Tamil and Malayalam languages.

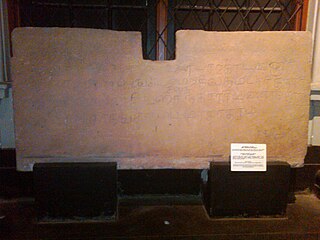

Tamil-Brahmi, also known as Tamili or Damili, was a variant of the Brahmi script in southern India. It was used to write inscriptions in the early form of Old Tamil. The Tamil-Brahmi script has been paleographically and stratigraphically dated between the third century BCE and the first century CE, and it constitutes the earliest known writing system evidenced in many parts of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Sri Lanka. Tamil Brahmi inscriptions have been found on cave entrances, stone beds, potsherds, jar burials, coins, seals, and rings.

Iravatham Mahadevan was an Indian epigraphist and civil servant, known for his decipherment of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions and for his expertise on the epigraphy of the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Kalinga script or Southern Nagari is a Brahmic script used in the region of what is now modern-day Odisha, India and was primarily used to write Odia language in the inscriptions of the kingdom of Kalinga which was under the reign of early Eastern Ganga dynasty. By the 12th century, with the defeat of the Somavamshi dynasty by the Eastern Ganga monarch Anantavarman Chodaganga and the subsequent reunification of the Trikalinga(the three regions of ancient Odra- Kalinga, Utkala and Dakshina Koshala) region, the Kalinga script got replaced by the Siddhaṃ script-derived Proto-Oriya script which became the ancestor of the modern Odia script.

There are literary, archaeological, epigraphic and numismatic sources of ancient Tamil history. The foremost among these sources is the Sangam literature, generally dated to 5th century BCE to 3rd century CE. The poems in Sangam literature contain vivid descriptions of the different aspects of life and society in Tamilakam during this age; scholars agree that, for the most part, these are reliable accounts. Greek and Roman literature, around the dawn of the Christian era, give details of the maritime trade between Tamilakam and the Roman empire, including the names and locations of many ports on both coasts of the Tamil country. There are evidences as could be seen comparing standard forms of Sumerian literature and those recovered through present form of Tamil, for example the word for father in Sumerian transliteration is given as, "a-ia" that could easily be compared with Tamil word, "ayya". This also places ancient form of Tamil to early Sumerian period, say as ancient as 3500 BC.

The Kotagama inscription found in Kegalle District in Sri Lanka is a record of victory left by the Aryacakravarti kings of the Jaffna Kingdom in western Sri Lanka. The inscription reads;

"The women-folks of lords of Anurai who did not submit to Ariyan of Cinkainakar of foaming and resounding waters shed tears from eyes that glinted like spears and performed the rites of pouring water with gingerly seed from the bejeweled lotus like hands."

Tissamaharama is a town in Hambantota District, Southern Province, Sri Lanka.

Kandarodai is a small hamlet and archaeological site of Chunnakam town, a suburb in Jaffna District, Sri Lanka.

The Anuradhapura period was a period in the history of Sri Lanka of the Anuradhapura Kingdom from 377 BCE to 1017 CE. The period begins when Pandukabhaya, King of Upatissa Nuwara moved the administration to Anuradhapura, becoming the kingdom's first monarch. Anuradhapura is heralded as an ancient cosmopolitan citadel with diverse populations.

The Anaikoddai seal is a soapstone seal that was found in Anaikoddai, Sri Lanka during archeological excavations of a megalithic burial site by a team of researchers from the University of Jaffna. The seal was originally part of a signet ring and contains one of the oldest Brahmi inscriptions mixed with megalithic graffiti symbols found on the island. It was dated paleographically to the early third century BC.

Megalithic markings, megalithic graffiti marks, megalithic symbols or non-Brahmi symbols are markings found on mostly potsherds found in Central India, South India and Sri Lanka during the Megalithic Iron Age in India. A number of scholars have tried to decipher the symbols since 1878, and currently there is no consensus as to whether they constitute undeciphered writing or graffiti or symbols without any syllabic or alphabetic meaning.

Mangulam or Mankulam is a village in Madurai district, Tamil Nadu, India. It is located 25 kilometres (16 mi) from Madurai. The inscriptions discovered in the region are the earliest Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions.

This is a list of archaeological artefacts and epigraphs which have Tamil inscriptions. Of the approximately 100,000 inscriptions found by the Archaeological Survey of India in India, about 60,000 were in Tamil Nadu

Tamil inscriptions in Sri Lanka date from the centuries before Christ to the modern era. The vast majority of inscriptions date to the centuries following the 10th century AD, and were issued under the reigns of both Tamil and Sinhala rulers alike. Out of the Tamil rulers, almost all surviving inscriptions were issued under the occupying Chola dynasty, whilst one stone inscription and coins of the Jaffna Kingdom have also been found.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Falk, H. (2014). "Owners' Graffiti on Pottery from Tissamaharama". Zeitschrift für Archäologie Aussereuropäischer Kulturen. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag: 45–94.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mahathevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu . Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ragupathy, P (28 June 2010). "Tissamaharama potsherd evidences ordinary early Tamils among population". Tamilnet. Tamilnet. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Somadeva, R. (2010). "තිස්සමහාරාම කුරුටු ලිපියේ ජර්මානු කියැවීම ශාස්ත්රීය නොමග යැවීමක්ද? (In Sinhala)". Dinithi. I (Part IV): 2–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pushparatnam, P. (2014). "Tamil Brahmi Inscription Belonging to 2200 years ago, Discovered by German Archaeological Team in Southern Sri Lanka". Jaffna University International Research Conference: 541–542.

- ↑ "Tissamaharama potsherd with alleged Tamil Brahmi inscription".

- ↑ Mahadevan 2003 , p. 195

- ↑ Paranavitana, S (1970). Inscriptions of Ceylon; Vol I. The Department of Archaeology Ceylon. p. 6.

- ↑ Mahadevan 2003 , pp. 179–180

- ↑ Mahadevan 2003 , p. 180