The National Security Act of 1947 was a law enacting major restructuring of the United States government's military and intelligence agencies following World War II. The majority of the provisions of the act took effect on September 18, 1947, the day after the Senate confirmed James Forrestal as the first secretary of defense.

Alben William Barkley was an American lawyer and politician from Kentucky who served as the 35th vice president of the United States from 1949 to 1953 under President Harry S. Truman. In 1905, he was elected to local offices and in 1912 as a U.S. representative. Serving in both houses of Congress, he was a liberal Democrat, supporting President Woodrow Wilson's New Freedom domestic agenda and foreign policy.

Husband Edward Kimmel was a United States Navy four-star admiral who was the commander in chief of the United States Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT) during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was removed from that command after the attack, in December 1941, and was reverted to his permanent two-star rank of rear admiral due to no longer holding a four-star assignment. He retired from the Navy in early 1942. The United States Senate voted to restore Kimmel's permanent rank to four stars in 1999, but President Clinton did not act on the resolution, and neither have any of his successors.

The 82nd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 1951, to January 3, 1953, during the last two years of President Harry S. Truman's second term in office.

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Nations. He is best known for leading the Republican Party from a foreign policy of isolationism to one of internationalism, and supporting the Cold War, the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and NATO. He served as president pro tempore of the United States Senate from 1947 to 1949.

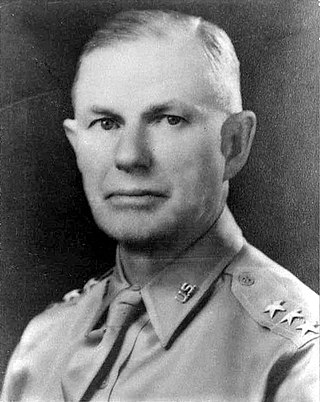

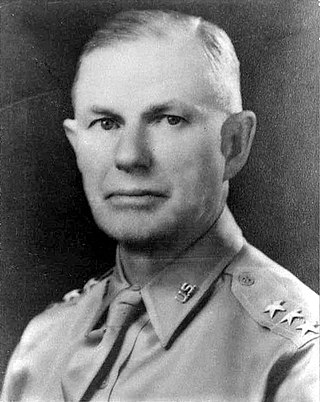

Walter Campbell Short was a lieutenant general and major general of the United States Army and the U.S. military commander responsible for the defense of U.S. military installations in Hawaii at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

A select or special committee of the United States Congress is a congressional committee appointed to perform a special function that is beyond the authority or capacity of a standing committee. A select committee is usually created by a resolution that outlines its duties and powers and the procedures for appointing members. Select and special committees are often investigative, rather than legislative, in nature though some select and special committees have the authority to draft and report legislation.

The Joint Inquiry into Intelligence Community Activities before and after the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001, is the official name of the inquiry conducted by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence into the activities of the U.S. Intelligence Community in connection with the attacks of September 11, 2001. The investigation began in February 2002 and the final report was released in December 2002.

Frank Comerford Walker was an American lawyer and politician. He was the United States Postmaster General from 1940 until 1945, and the chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1943 until 1944.

The 80th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January 3, 1947, to January 3, 1949, during the third and fourth years of Harry S. Truman's presidency. The apportionment of seats in this House of Representatives was based on the 1940 United States census.

The 77th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 1941, to January 3, 1943, during the ninth and tenth years of Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidency. The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the 1930 United States census.

The 79th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 1945, to January 3, 1947, during the last months of Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidency, and the first two years of Harry Truman's presidency. The apportionment of seats in this House of Representatives was based on the 1940 United States census.

The 78th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 1943, to January 3, 1945, during the last two years of Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidency. The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the 1940 United States census.

The 76th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 1939, to January 3, 1941, during the seventh and eighth years of Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidency. The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the 1930 United States census.

The Truman Committee, formally known as the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, was a United States Congressional investigative body, headed by Senator Harry S. Truman. The bipartisan special committee was formed in March 1941 to find and correct problems in US war production with waste, inefficiency, and war profiteering. The Truman Committee proved to be one of the most successful investigative efforts ever mounted by the U.S. government: an initial budget of $15,000 was expanded over three years to $360,000 to save an estimated $10–15 billion in military spending and thousands of lives of U.S. servicemen. For comparison, the entire cost of the simultaneous Manhattan Project, which created the first atomic bombs, was $2 billion. Chairing the committee helped Truman make a name for himself beyond his political machine origins and was a major factor in the decision to nominate him as vice president, which would propel him to the presidency after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

John William Murphy was a United States representative from Pennsylvania and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania.

The First Congress of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, also known as the Postwar Congress, and the Liberation Congress, refers to the meeting of the bicameral legislature composed of the Senate and House of Representatives, from 1945 to 1946. The meeting only convened after the reestablishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines in 1945 when President Sergio Osmeña called it to hold five special sessions. Osmeña had replaced Manuel L. Quezon as president after the former died in exile in the United States in 1944.

Ralph Owen Brewster was an American politician from Maine. Brewster, a Republican, served as the 54th Governor of Maine from 1925 to 1929, in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1935 to 1941 and in the U.S. Senate from 1941 to 1952. Brewster was a close confidant of Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin and an antagonist of Howard Hughes. He was defeated by Frederick G. Payne, whose campaign was heavily funded by Hughes, in the 1952 Republican primary.

The Military Intelligence Division was the military intelligence branch of the United States Army and United States Department of War from May 1917 to March 1942. It was preceded by the Military Information Division and the General Staff Second Division and in 1942 was reorganised as the Military Intelligence Service.

The presidency of Harry S. Truman began on April 12, 1945, when Harry S. Truman became the 33rd president upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953.