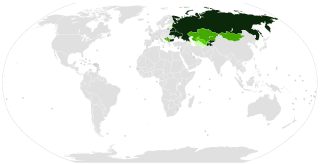

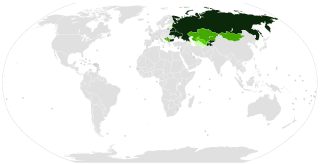

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic languages originated in a region of East Asia spanning from Mongolia to Northwest China, where Proto-Turkic is thought to have been spoken, from where they expanded to Central Asia and farther west during the first millennium. They are characterized as a dialect continuum.

Kazakh or Qazaq is a Turkic language of the Kipchak branch spoken in Central Asia by Kazakhs. It is closely related to Nogai, Kyrgyz and Karakalpak. It is the official language of Kazakhstan and a significant minority language in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in Xinjiang, north-western China, and in the Bayan-Ölgii Province of western Mongolia. The language is also spoken by many ethnic Kazakhs throughout the former Soviet Union, Germany, and Turkey.

Kyrgyz is a Turkic language of the Kipchak branch spoken in Central Asia. Kyrgyz is the official language of Kyrgyzstan and a significant minority language in the Kizilsu Kyrgyz Autonomous Prefecture in Xinjiang, China and in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of Tajikistan. There is a very high level of mutual intelligibility between Kyrgyz, Kazakh, and Altay. A dialect of Kyrgyz known as Pamiri Kyrgyz is spoken in north-eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. Kyrgyz is also spoken by many ethnic Kyrgyz through the former Soviet Union, Afghanistan, Turkey, parts of northern Pakistan, and Russia.

Tatar is a Turkic language spoken by the Volga Tatars mainly located in modern Tatarstan, as well as Siberia. It should not be confused with Crimean Tatar or Siberian Tatar, which are closely related but belong to different subgroups of the Kipchak languages.

Bashkir or Bashkort is a Turkic language belonging to the Kipchak branch. It is co-official with Russian in Bashkortostan. It is spoken by 1.09 million native speakers in Russia, as well as in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Estonia and other neighboring post-Soviet states, and among the Bashkir diaspora. It has three dialect groups: Southern, Eastern and Northwestern.

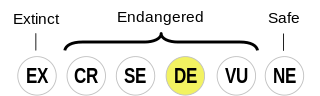

The Karaim language, also known by its Hebrew name Lashon Kedar is a Turkic language belonging to the Kipchak group, with Hebrew influences, similarly to Yiddish or Judaeo-Spanish. It is spoken by only a few dozen Crimean Karaites in Lithuania, Poland, Crimea, and Galicia in Ukraine. The three main dialects are those of Crimea, Trakai-Vilnius and Lutsk-Halych, all of which are critically endangered. The Lithuanian dialect of Karaim is spoken mainly in the town of Trakai by a small community living there since the 14th century.

Crimean Tatar, also called Crimean, is a moribund Kipchak Turkic language spoken in Crimea and the Crimean Tatar diasporas of Uzbekistan, Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria, as well as small communities in the United States and Canada. It should not be confused with Tatar, spoken in Tatarstan and adjacent regions in Russia; the two languages are related, but belong to different subgroups of the Kipchak languages, while maintaining a significant degree of mutual intelligibility. Crimean Tatar has been extensively influenced by nearby Oghuz dialects and is also mutually intelligible with them, to varying degrees.

Nogai also known as Noğay, Noghay, Nogay, or Nogai Tatar, is a moribund Turkic language spoken in Southeastern European Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey. It is the ancestral language of the Nogais. As a member of the Kipchak branch, it is closely related to Kazakh, Karakalpak and Crimean Tatar. In 2014 the first Nogai novel was published, written in the Latin alphabet.

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group and nation native to Crimea. The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, uniting Cumans, who appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with other peoples who had inhabited Crimea since ancient times and gradually underwent Tatarization, including Ukrainian Greeks, Italians, Goths, Sarmatians and many others.

Cuman or Kuman was a West Kipchak Turkic language spoken by the Cumans and Kipchaks; the language was similar to today's various languages of the West Kipchak branch. Cuman is documented in medieval works, including the Codex Cumanicus, and in early modern manuscripts, like the notebook of Benedictine monk Johannes ex Grafing. It was a literary language in Central and Eastern Europe that left a rich literary inheritance. The language became the main language of the Golden Horde.

Karakalpak is a Turkic language spoken by Karakalpaks in Karakalpakstan. It is divided into two dialects, Northeastern Karakalpak and Southwestern Karakalpak. It developed alongside Nogai and neighbouring Kazakh languages, being markedly influenced by both. Typologically, Karakalpak belongs to the Kipchak branch of the Turkic languages, thus being closely related to and highly mutually intelligible with Kazakh and Nogai.

The Common Turkic alphabet is a project of a single Latin alphabet for all Turkic languages based on a slightly modified Turkish alphabet, with 34 letters recognised by the Organization of Turkic States. Its letters are as follows:

Krymchak is a moribund Turkic language spoken in Crimea by the Krymchak people. The Krymchak community was composed of Jewish immigrants who arrived from all over Europe and Asia and who continuously added to the Krymchak population. The Krymchak language, as well as culture and daily life, was similar to Crimean Tatar, the peninsula's majority population, with the addition of a significant Hebrew influence.

The Kipchak languages are a sub-branch of the Turkic language family spoken by approximately 28 million people in much of Central Asia and Eastern Europe, spanning from Ukraine to China. Some of the most widely spoken languages in this group are Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Tatar.

The Urums are several groups of Turkic-speaking Greek Orthodox people native to Crimea. The emergence and development of the Urum identity took place from 13th to the 17th centuries. Bringing together the Hellenes along with Greek-speaking Crimean Goths, with other indigenous groups that had long inhabited the region, resulting in a gradual transformation of their collective identity.

Numerous Cyrillic alphabets are based on the Cyrillic script. The early Cyrillic alphabet was developed in the 9th century AD and replaced the earlier Glagolitic script developed by the Bulgarian theologians Cyril and Methodius. It is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, Slavic origin, and non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages. About half of them are in Russia. Cyrillic is one of the most-used writing systems in the world. The creator is Saint Clement of Ohrid from the Preslav literary school in the First Bulgarian Empire.

Mariupolitan Greek, or Crimean Greek also known as Tauro-Romaic or Ruméika, is a Greek dialect spoken by the ethnic Greeks living along the northern coast of the Sea of Azov, in southeastern Ukraine; the community itself is referred to as Azov Greeks. Although Rumeíka, along with the Urum language, remained the main language spoken by the Azov Greeks well into the 20th century, currently it is used by only a small part of Ukraine's ethnic Greeks.

Siberian Tatar is a moribund Turkic language spoken in Western Siberia, Russia, primarily in the oblasts of Tyumen, Novosibirsk, Omsk but also in Tomsk and Kemerovo. According to Marcel Erdal, due to its particular characteristics, Siberian Tatar can be considered as a bridge to Siberian Turkic languages.

Armeno-Kipchak was a Turkic language belonging to the Kipchak branch of the family that was spoken in Crimea during the 14–15th centuries. The language has been documented from the literary monuments of 16–17th centuries written in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the Armenian script. Armeno-Kipchak resembles the language of Codex Cumanicus, which was compiled in the 13th century.