Huntsman spiders, members of the family Sparassidae, are known by this name because of their speed and mode of hunting. They are also called giant crab spiders because of their size and appearance. Larger species sometimes are referred to as wood spiders, because of their preference for woody places. In southern Africa the genus Palystes are known as rain spiders or lizard-eating spiders. Commonly, they are confused with baboon spiders from the Mygalomorphae infraorder, which are not closely related.

Nursery web spiders (Pisauridae) are a family of araneomorph spiders first described by Eugène Simon in 1890. Females of the family are known for building special nursery webs. When their eggs are about to hatch, a female spider builds a tent-like web, places her egg sac inside, and stands guard outside, hence the family's common name. Like wolf spiders, however, nursery web spiders are roaming hunters that don't use webs for catching prey.

Orb-weaver spiders are members of the spider family Araneidae. They are the most common group of builders of spiral wheel-shaped webs often found in gardens, fields, and forests. The English word "orb" can mean "circular", hence the English name of the group. Araneids have eight similar eyes, hairy or spiny legs, and no stridulating organs.

Tegenaria is a genus of fast-running funnel weavers that occupy much of the Northern Hemisphere except for Japan and Indonesia. It was first described by Pierre André Latreille in 1804, though many of its species have been moved elsewhere. The majority of these were moved to Eratigena, including the giant house spider and the hobo spider.

Dolomedes is a genus of large spiders of the family Pisauridae. They are also known as fishing spiders, raft spiders, dock spiders or wharf spiders. Almost all Dolomedes species are semiaquatic, with the exception of the tree-dwelling D. albineus of the southeastern United States. Many species have a striking pale stripe down each side of the body.

Hersiliidae is a tropical and subtropical family of spiders first described by Tamerlan Thorell in 1869, which are commonly known as tree trunk spiders. They have two prominent spinnerets that are almost as long as their abdomen, earning them another nickname, the "two-tailed spiders". They range in size from 10 to 18 mm long. Rather than using a web that captures prey directly, they lay a light coating of threads over an area of tree bark and wait for an insect to stray onto the patch. When this happens, they encircle their spinnerets around their prey while casting silk on it. When the insect is immobilized, they can bite it through the shroud.

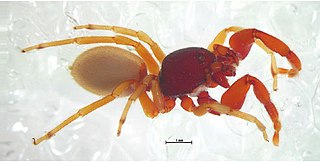

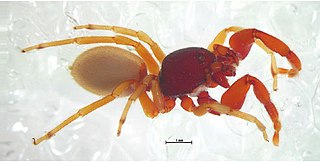

Xysticus is a genus of ground crab spiders described by C. L. Koch in 1835, belonging to the order Araneae, family Thomisidae. The genus name is derived from the Ancient Greek root xyst, meaning "scraped, scraper".

Pellenes is a genus of jumping spiders that was first described by Eugène Louis Simon in 1876. It is considered a senior synonym of Hyllothyene.

Palpimanidae, also known as palp-footed spiders, is a family of araneomorph spiders first described by Tamerlan Thorell in 1890. They are widely distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, the Mediterranean and one in Uzbekistan, but not Australia. They are not common and there is a high degree of endemism.

Cheiracanthium, commonly called yellow sac spiders, is a genus of araneomorph spiders in the family Cheiracanthiidae, and was first described by Carl Ludwig Koch in 1839. They are usually pale in colour, and have an abdomen that can range from yellow to beige. Both sexes range in size from 5 to 10 millimetres. They are unique among common house spiders because their tarsi do not point either outward, like members of Tegenaria, or inward, like members of Araneus), making them easier to identify.

Alopecosa is a spider genus in the family Lycosidae, with about 160 species. They have a largely Eurasian distribution, although some species are found in North Africa and North America.

Drassodes is a genus of ground spiders that was first described by Niklas Westring in 1851. They are brown, gray, and red spiders that live under rocks or bark in mostly dry habitats, and are generally 3.8 to 11.6 millimetres long, but can reach up to 20 millimetres (0.79 in) in length.

Theridion is a genus of tangle-web spiders with a worldwide distribution. Notable species are the Hawaiian happy face spider (T. grallator), named for the iconic symbol on its abdomen, and T. nigroannulatum, one of few spider species that lives in social groups, attacking prey en masse to overwhelm them as a team.

Hogna is a genus of wolf spiders with more than 200 described species. It is found on all continents except Antarctica.

Pardosa is a large genus of wolf spiders, commonly known as the thin-legged wolf spiders. It was first described by C. L. Koch, in 1847, with more than 500 described species that are found in all regions of the world.

The Artoriinae are a subfamily of wolf spiders. The monophyly of the subfamily has been confirmed in a molecular phylogenetic study, although the relationships among the subfamilies was shown to be less certain.

Allocosa is a spider genus of the wolf spider family, Lycosidae. The 130 or more recognized species are spread worldwide.

Hippasa is a genus of spiders in the wolf spider family Lycosidae, first described by Eugène Simon in 1885.

Artoria is a genus of spiders in the family Lycosidae. It was first described in 1877 by Tamerlan Thorell, and the type species is Artoria parvula. In 1960, Roewer erected the genera Artoriella and Trabeola. However, in 2002, Volker Framenau reviewed Artoria and synonymised both these genera with Artoria.