Yoga for therapeutic purposes is the use of yoga as exercise, consisting mainly of postures called asanas, as a gentle form of exercise and relaxation applied specifically with the intention of improving health. This form of yoga is widely practised in classes, and may involve meditation, imagery, breath work (pranayama) and music. [1]

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting mainly of postures (asanas), often connected by flowing sequences called vinyasas, sometimes accompanied by rhythmic breathing (pranayama), and often ending with relaxation or meditation. Yoga in this form has become familiar across the world, especially in America and Europe. Like other forms of modern yoga, it is derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, and is sometimes so named, but it is generally simply called "yoga". This is despite the existence of multiple older traditions of yoga within Hinduism dating back to the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, some not involving asanas at all, and despite the fact that in no tradition was the practice of asanas central. Academics have given yoga as exercise a variety of names, including "modern postural yoga", "modern transnational yoga", and "transnational anglophone yoga".

An asana is a body posture, originally a sitting pose for meditation, and later in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses to the meditation seats. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

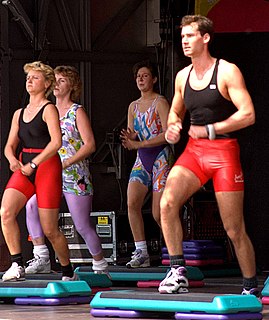

Exercise is any bodily activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness. It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, preventing aging, developing muscles and the cardiovascular system, honing athletic skills, weight loss or maintenance, improving health and also for enjoyment. Many individuals choose to exercise outdoors where they can congregate in groups, socialize, and enhance well-being.

Contents

- Context

- Types of claim

- Magical powers

- Biomedical claims for marketing purposes

- Evidence-based medical claims

- Research

- Methodology

- Mechanisms

- Low back pain

- Mental disorders

- Other conditions

- Safety

- See also

- References

- Sources

- External links

At least three types of health claim have been made for yoga: magical claims for medieval haṭha yoga, including the power of healing; unsupported claims of benefits to organ systems from the practice of asanas; and more or less well supported claims of specific medical and psychological benefits from studies of differing sizes using a wide variety of methodologies.

Siddhis are spiritual, paranormal, supernatural, or otherwise magical powers, abilities, and attainments that are the products of spiritual advancement through sādhanās such as meditation and yoga. The term ṛddhi is often used interchangeably in Buddhism.

Organs are groups of tissues with similar functions. Plant and animal life relies on many organs that coexist in organ systems.

Systematic reviews have found beneficial effects of yoga on low back pain [2] and depression, [3] but despite much investigation little or no evidence for benefit for specific medical conditions. Study of trauma-sensitive yoga has been hampered by weak methodology. [4]

Low back pain (LBP) is a common disorder involving the muscles, nerves, and bones of the back. Pain can vary from a dull constant ache to a sudden sharp feeling. Low back pain may be classified by duration as acute, sub-chronic, or chronic. The condition may be further classified by the underlying cause as either mechanical, non-mechanical, or referred pain. The symptoms of low back pain usually improve within a few weeks from the time they start, with 40–90% of people completely better by six weeks.

Depression is a state of low mood and aversion to activity. It can affect a person's thoughts, behavior, motivation, feelings, and sense of well-being. It may feature sadness, difficulty in thinking and concentration and a significant increase/decrease in appetite and time spent sleeping, and people experiencing depression may have feelings of dejection, hopelessness and, sometimes, suicidal thoughts. It can either be short term or long term. Depressed mood is a symptom of some mood disorders such as major depressive disorder or dysthymia; it is a normal temporary reaction to life events, such as the loss of a loved one; and it is also a symptom of some physical diseases and a side effect of some drugs and medical treatments.

Trauma-sensitive yoga is yoga as exercise, adapted from 2002 onwards for work with individuals affected by psychological trauma. The goal of trauma-sensitive yoga is for trauma survivors to develop a greater sense of mind-body connection, ease their physiological experiences of trauma, gain a greater sense of ownership over their bodies, and augment their overall well-being.