Hydraulics is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counterpart of pneumatics, which concerns gases. Fluid mechanics provides the theoretical foundation for hydraulics, which focuses on the applied engineering using the properties of fluids. In its fluid power applications, hydraulics is used for the generation, control, and transmission of power by the use of pressurized liquids. Hydraulic topics range through some parts of science and most of engineering modules, and cover concepts such as pipe flow, dam design, fluidics and fluid control circuitry. The principles of hydraulics are in use naturally in the human body within the vascular system and erectile tissue. Free surface hydraulics is the branch of hydraulics dealing with free surface flow, such as occurring in rivers, canals, lakes, estuaries and seas. Its sub-field open-channel flow studies the flow in open channels.

A stream bed or streambed is the channel bottom of a stream or river, the physical confine of the normal water flow. The lateral confines or channel margins are known as the stream banks or river banks, during all but flood stage. Under certain conditions a river can branch from one stream bed to multiple stream beds. A flood occurs when a stream overflows its banks and flows onto its flood plain. As a general rule, the bed is the part of the channel up to the normal water line, and the banks are that part above the normal water line. However, because water flow varies, this differentiation is subject to local interpretation. Usually, the bed is kept clear of terrestrial vegetation, whereas the banks are subjected to water flow only during unusual or perhaps infrequent high water stages and therefore might support vegetation some or much of the time.

A weir or low head dam is a barrier across the width of a river that alters the flow characteristics of water and usually results in a change in the height of the river level. There are many designs of weir, but commonly water flows freely over the top of the weir crest before cascading down to a lower level.

A flume is a human-made channel for water in the form of an open declined gravity chute whose walls are raised above the surrounding terrain, in contrast to a trench or ditch. Flumes are not to be confused with aqueducts, which are built to transport water, rather than transporting materials using flowing water as a flume does. Flumes route water from a diversion dam or weir to a desired materiel collection location.

Hydraulic machines are machinery and tools that use liquid fluid power to do simple work, operated by the use of hydraulics, where a liquid is the powering medium. In heavy equipment and other types of machine, hydraulic fluid is transmitted throughout the machine to various hydraulic motors and hydraulic cylinders and becomes pressurised according to the resistance present. The fluid is controlled directly or automatically by control valves and distributed through hoses and tubes.

Thermal hydraulics is the study of hydraulic flow in thermal fluids. The area can be mainly divided into three parts: thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and heat transfer, but they are often closely linked to each other. A common example is steam generation in power plants and the associated energy transfer to mechanical motion and the change of states of the water while undergoing this process. Thermal-hydraulic analysis can determine important parameters for reactor design such as plant efficiency and coolability of the system.

Hydraulic head or piezometric head is a specific measurement of liquid pressure above a vertical datum.

The Manning formula is an empirical formula estimating the average velocity of a liquid flowing in a conduit that does not completely enclose the liquid, i.e., open channel flow. However, this equation is also used for calculation of flow variables in case of flow in partially full conduits, as they also possess a free surface like that of open channel flow. All flow in so-called open channels is driven by gravity. It was first presented by the French engineer Philippe Gauckler in 1867, and later re-developed by the Irish engineer Robert Manning in 1890.

Open-channel flow, a branch of hydraulics and fluid mechanics, is a type of liquid flow within a conduit with a free surface, known as a channel. The other type of flow within a conduit is pipe flow. These two types of flow are similar in many ways but differ in one important respect: the free surface. Open-channel flow has a free surface, whereas pipe flow does not.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Storm Water Management Model is a dynamic rainfall–runoff–subsurface runoff simulation model used for single-event to long-term (continuous) simulation of the surface/subsurface hydrology quantity and quality from primarily urban/suburban areas. It can simulate the Rainfall- runoff, runoff, evaporation, infiltration and groundwater connection for roots, streets, grassed areas, rain gardens and ditches and pipes, for example. The hydrology component of SWMM operates on a collection of subcatchment areas divided into impervious and pervious areas with and without depression storage to predict runoff and pollutant loads from precipitation, evaporation and infiltration losses from each of the subcatchment. Besides, low impact development (LID) and best management practice areas on the subcatchment can be modeled to reduce the impervious and pervious runoff. The routing or hydraulics section of SWMM transports this water and possible associated water quality constituents through a system of closed pipes, open channels, storage/treatment devices, ponds, storages, pumps, orifices, weirs, outlets, outfalls and other regulators. SWMM tracks the quantity and quality of the flow generated within each subcatchment, and the flow rate, flow depth, and quality of water in each pipe and channel during a simulation period composed of multiple fixed or variable time steps. The water quality constituents such as water quality constituents can be simulated from buildup on the subcatchments through washoff to a hydraulic network with optional first order decay and linked pollutant removal, best management practice and low-impact development removal and treatment can be simulated at selected storage nodes. SWMM is one of the hydrology transport models which the EPA and other agencies have applied widely throughout North America and through consultants and universities throughout the world. The latest update notes and new features can be found on the EPA website in the download section. Recently added in November 2015 were the EPA SWMM 5.1 Hydrology Manual and in 2016 the EPA SWMM 5.1 Hydraulic Manual and EPA SWMM 5.1 Water Quality Volume (III) + Errata”

Pipe flow, a branch of hydraulics and fluid mechanics, is a type of liquid flow within a closed conduit. The other type of flow within a conduit is open channel flow. These two types of flow are similar in many ways, but differ in one important aspect. Pipe flow does not have a free surface which is found in open-channel flow. Pipe flow, being confined within closed conduit, does not exert direct atmospheric pressure, but does exert hydraulic pressure on the conduit.

The depth–slope product is used to calculate the shear stress at the bed of an open channel containing fluid that is undergoing steady, uniform flow. It is widely used in river engineering, stream restoration, sedimentology, and fluvial geomorphology. It is the product of the water depth and the mean bed slope, along with the acceleration due to gravity and density of the fluid.

Bridge scour is the removal of sediment such as sand and gravel from around bridge abutments or piers. Scour, caused by swiftly moving water, can scoop out scour holes, compromising the integrity of a structure.

Hubert Chanson is a professor in hydraulic engineering and applied fluid mechanics in the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Queensland since 1990. He lectures civil and environmental engineering students in a variety of courses including fluid mechanics, hydraulic engineering, civil design, engineering history, coastal processes and environmental modelling. His research interests include the hydraulics of open channel flow, the design of hydraulic structures, experimental investigations of two-phase flows, coastal and estuarine hydrodynamics, water quality modelling, environmental management and natural resources.

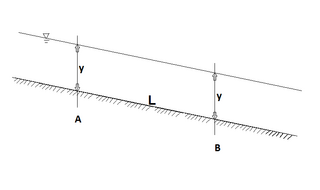

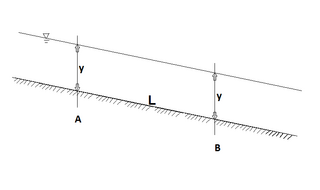

A venturi flume is a critical-flow open flume with a constricted flow which causes a drop in the hydraulic grade line, creating a critical depth.

The Reynolds number is an important dimensionless quantity in fluid mechanics used to help predict flow patterns in different fluid flow situations. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be dominated by laminar (sheet-like) flow, while at high Reynolds numbers turbulence results from differences in the fluid's speed and direction, which may sometimes intersect or even move counter to the overall direction of the flow. These eddy currents begin to churn the flow, using up energy in the process, which for liquids increases the chances of cavitation. The Reynolds number has wide applications, ranging from liquid flow in a pipe to the passage of air over an aircraft wing. It is used to predict the transition from laminar to turbulent flow, and is used in the scaling of similar but different-sized flow situations, such as between an aircraft model in a wind tunnel and the full size version. The predictions of the onset of turbulence and the ability to calculate scaling effects can be used to help predict fluid behaviour on a larger scale, such as in local or global air or water movement and thereby the associated meteorological and climatological effects.

Hydraulic jump in a rectangular channel, also known as classical jump, is a natural phenomenon that occurs whenever flow changes from supercritical to subcritical flow. In this transition, the water surface rises abruptly, surface rollers are formed, intense mixing occurs, air is entrained, and often a large amount of energy is dissipated. In other words, a hydraulic jump happens when a higher velocity, v1, supercritical flow upstream is met by a subcritical downstream flow with a decreased velocity, v2, and sufficient depth. Numeric models created using the standard step method or HEC-RAS are used to track supercritical and subcritical flows to determine where in a specific reach a hydraulic jump will form.

The standard step method (STM) is a computational technique utilized to estimate one-dimensional surface water profiles in open channels with gradually varied flow under steady state conditions. It uses a combination of the energy, momentum, and continuity equations to determine water depth with a given a friction slope , channel slope , channel geometry, and also a given flow rate. In practice, this technique is widely used through the computer program HEC-RAS, developed by the US Army Corps of Engineers Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC).

Chow, V. T. (2008). Open-channel hydraulics. Caldwell, New Jersey: Blackburn Press.