Anointing of the sick, known also by other names such as unction, is a form of religious anointing or "unction" for the benefit of a sick person. It is practiced by many Christian churches and denominations.

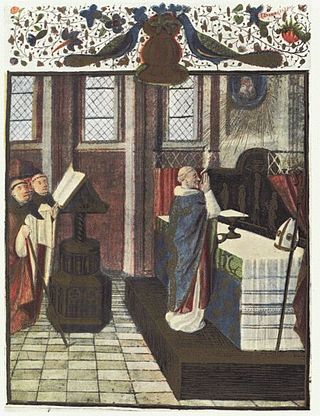

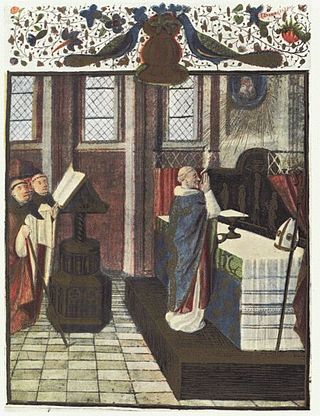

The Eucharist, also known as Holy Communion, Blessed Sacrament and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. Christians believe that the rite was instituted by Jesus at the Last Supper, the night before his crucifixion, giving his disciples bread and wine. Passages in the New Testament state that he commanded them to "do this in memory of me" while referring to the bread as "my body" and the cup of wine as "the blood of my covenant, which is poured out for many". According to the Synoptic Gospels this was at a Passover meal.

In certain Christian denominations, holy orders are the ordained ministries of bishop, priest (presbyter), and deacon, and the sacrament or rite by which candidates are ordained to those orders. Churches recognizing these orders include the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, Assyrian, Old Catholic, Independent Catholic and some Lutheran churches. Except for Lutherans and some Anglicans, these churches regard ordination as a sacrament.

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term Mass is commonly used in the Catholic Church, Western Rite Orthodoxy, Old Catholicism, and Independent Catholicism. The term is also used in some Lutheran churches, as well as in some Anglican churches, and on rare occasion by other Protestant churches.

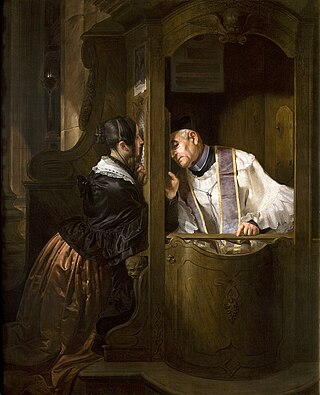

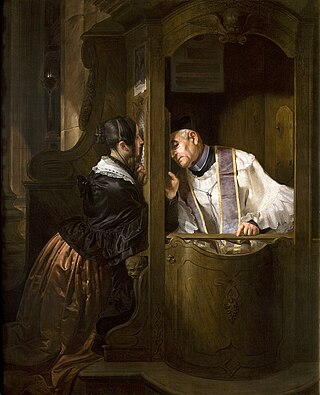

Confession, in many religions, is the acknowledgment of sinful thoughts and actions. This may occur directly to a god or to fellow people.

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of repentance for sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession. It also plays a part in confession among Anglicans and Methodists, in which it is a rite, as well as among other Protestants. The word penance derives from Old French and Latin paenitentia, both of which derive from the same root meaning repentance, the desire to be forgiven. Penance and repentance, similar in their derivation and original sense, have come to symbolize conflicting views of the essence of repentance, arising from the controversy as to the respective merits of "faith" and "good works". Word derivations occur in many languages.

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on of hands.

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Christian priests and experienced by Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, although the theology and the practice of absolution vary between Christian denominations.

Ex opere operato is a Latin phrase meaning "from the work performed" and, in reference to sacraments, signifies that they derive their efficacy, not from the minister or the recipient, but from the sacrament considered independently of the merits of the minister or the recipient. According to the ex opere operato interpretation of the sacraments, any positive effect comes not from their worthiness or faith but from the sacrament as an instrument of God.

Eucharistic discipline is the term applied to the regulations and practices associated with an individual preparing for the reception of the Eucharist. Different Christian traditions require varying degrees of preparation, which may include a period of fasting, prayer, repentance, and confession.

Eucharistic theology is a branch of Christian theology which treats doctrines concerning the Holy Eucharist, also commonly known as the Lord's Supper and Holy Communion. It exists exclusively in Christianity, as others generally do not contain a Eucharistic ceremony.

Catholicity is a concept of pertaining to beliefs and practices that are widely accepted by numerous Christian denominations, most notably by those Christian denominations that describe themselves as catholic in accordance with the Four Marks of the Church, as expressed in the Nicene Creed formulated at the First Council of Constantinople in 381: "[I believe] in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church." The English adjective catholic is derived from the Ancient Greek adjective καθολικός, meaning "general", "universal". Thus, "catholic" means that in the Church the wholeness of the Christian faith, full and complete, all-embracing, and with nothing lacking, is proclaimed to all people without excluding any part of the faith or any class or group of people. An early definition for what is "catholic" was summarized in what is known as the Vincentian Canon in the 5th century Commonitory: "what has been believed everywhere, always, and by all."

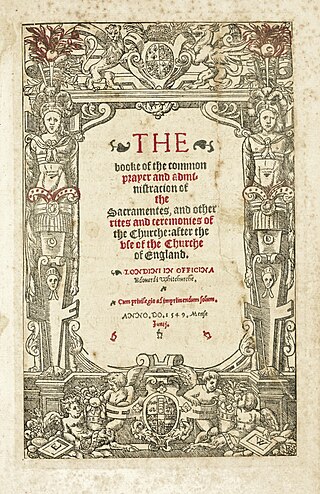

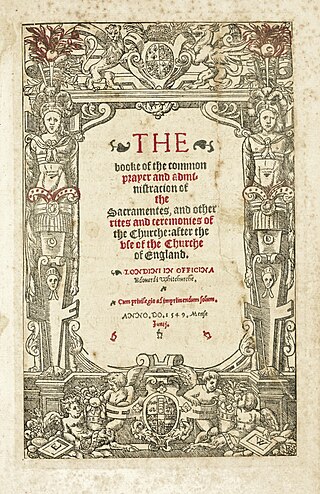

Anglican eucharistic theology is diverse in practice, reflecting the comprehensiveness of Anglicanism. Its sources include prayer book rubrics, writings on sacramental theology by Anglican divines, and the regulations and orientations of ecclesiastical provinces. The principal source material is the Book of Common Prayer, specifically its eucharistic prayers and Article XXVIII of the Thirty-Nine Articles. Article XXVIII comprises the foundational Anglican doctrinal statement about the Eucharist, although its interpretation varies among churches of the Anglican Communion and in different traditions of churchmanship such as Anglo-Catholicism and Evangelical Anglicanism.

The sacrament of holy orders in the Catholic Church includes three orders: bishops, priests, and deacons, in decreasing order of rank, collectively comprising the clergy. In the phrase "holy orders", the word "holy" means "set apart for a sacred purpose". The word "order" designates an established civil body or corporation with a hierarchy, and ordination means legal incorporation into an order. In context, therefore, a group with a hierarchical structure that is set apart for ministry in the Church.

Lay confession is confession in the religious sense, made to a lay person.

The Lutheran sacraments are "sacred acts of divine institution". Lutherans believe that, whenever they are properly administered by the use of the physical component commanded by God along with the divine words of institution, God is, in a way specific to each sacrament, present with the Word and physical component. They teach that God earnestly offers to all who receive the sacrament forgiveness of sins and eternal salvation. They teach that God also works in the recipients to get them to accept these blessings and to increase the assurance of their possession.

This is a glossary of terms used within the Catholic Church. Some terms used in everyday English have a different meaning in the context of the Catholic faith, including brother, confession, confirmation, exemption, faithful, father, ordinary, religious, sister, venerable, and vow.

There are seven sacraments of the Catholic Church, which according to Catholic theology were instituted by Jesus Christ and entrusted to the Church. Sacraments are visible rites seen as signs and efficacious channels of the grace of God to all those who receive them with the proper disposition.

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the reality of God, as well as a channel for God's grace. Many denominations, including the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian Anglican, Methodist, and Reformed, hold to the definition of sacrament formulated by Augustine of Hippo: an outward sign of an inward grace, that has been instituted by Jesus Christ. Sacraments signify God's grace in a way that is outwardly observable to the participant.

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the original version of the Book of Common Prayer, variations of which are still in use as the official liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican churches. Written during the English Reformation, the prayer book was largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, who borrowed from a large number of other sources. Evidence of Cranmer's Protestant theology can be seen throughout the book; however, the services maintain the traditional forms and sacramental language inherited from medieval Catholic liturgies. Criticised by Protestants for being too traditional, it was replaced by the significantly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer.