Related Research Articles

Hausa is a Chadic language that is spoken by the Hausa people in the northern parts of Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Benin and Togo, and the southern parts of Niger, and Chad, with significant minorities in Ivory Coast. A small number of speakers also exist in Sudan.

Historical linguistics, also termed diachronic linguistics, is the scientific study of language change over time. Principal concerns of historical linguistics include:

- to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages

- to reconstruct the pre-history of languages and to determine their relatedness, grouping them into language families

- to develop general theories about how and why language changes

- to describe the history of speech communities

- to study the history of words, i.e. etymology

- to explore the impact of cultural and social factors on language evolution.

A lingua franca, also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups of people who do not share a native language or dialect, particularly when it is a third language that is distinct from both of the speakers' native languages.

In linguistics, diglossia is a situation in which two dialects or languages are used by a single language community. In addition to the community's everyday or vernacular language variety, a second, highly codified lect is used in certain situations such as literature, formal education, or other specific settings, but not used normally for ordinary conversation. The H variety may have no native speakers within the community. In cases of three dialects, the term triglossia is used. When referring to two writing systems coexisting for a single language, the term digraphia is used.

Liberian English refers to the varieties of English spoken in Liberia. There are four such varieties:

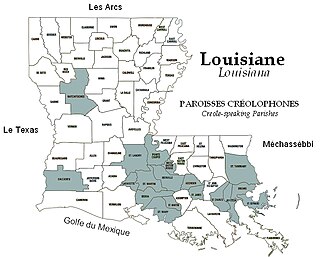

Louisiana Creole is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana. Also known as Kouri-Vini, it is spoken today by people who may racially identify as white, black, mixed, and Native American, as well as Cajun and Creole. It should not be confused with its sister language, Louisiana French, a dialect of the French language. Many Louisiana Creoles do not speak the Louisiana Creole language and may instead use French or English as their everyday languages.

Nigerian Pidgin, also known as Naija or Naijá in scholarship, is an English-based creole language spoken as a lingua franca across Nigeria. The language is sometimes referred to as Pijin, Brokun 'Ullu' or "Vernacular". It can be spoken as a pidgin, a creole, dialect or a decreolised acrolect by different speakers, who may switch between these forms depending on the social setting. In the 2010s, a common orthography was developed for Pidgin which has been gaining significant popularity in giving the language a harmonized writing system.

The Sierra Leonean Creole or Krio is an English-based creole language that is lingua franca and de facto national language spoken throughout the West African nation of Sierra Leone. Krio is spoken by 96 percent of the country's population, and it unites the different ethnic groups in the country, especially in their trade and social interaction with each other. Krio is the primary language of communication among Sierra Leoneans at home and abroad, and has also heavily influenced Sierra Leonean English. The language is native to the Sierra Leone Creole people, or Krios, a community of about 104,311 descendants of freed slaves from the West Indies, Canada, United States and the British Empire, and is spoken as a second language by millions of other Sierra Leoneans belonging to the country's indigenous tribes. Krio, along with English, is the official language of Sierra Leone.

Cameroonian Pidgin English, or Cameroonian Creole, is a language variety of Cameroon. It is also known as Kamtok. It is primarily spoken in the North West and South West English speaking regions. Five varieties are currently recognised:

An ethnolect is generally defined as a language variety that marks speakers as members of ethnic groups who originally used another language or distinctive variety. According to another definition, an ethnolect is any speech variety associated with a specific ethnic group. It may be a distinguishing mark of social identity, both within the group and for outsiders. The term combines the concepts of an ethnic group and dialect.

An English-based creole language is a creole language for which English was the lexifier, meaning that at the time of its formation the vocabulary of English served as the basis for the majority of the creole's lexicon. Most English creoles were formed in British colonies, following the great expansion of British naval military power and trade in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. The main categories of English-based creoles are Atlantic and Pacific.

West African Pidgin English, also known as Guinea Coast Creole English, is a West African pidgin language lexified by English and local African languages. It originated as a language of commerce between British and African slave traders during the period of the transatlantic slave trade. As of 2017, about 75 million people in Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana and Equatorial Guinea used the language.

Ghana is a multilingual country in which about eighty languages are spoken. Of these, English, which was inherited from the colonial era, is the official language and lingua franca. Of the languages indigenous to Ghana, Akan is the most widely spoken in the south. Dagbani is most widely spoken in the north.

There are over 525 native languages spoken in Nigeria. The official language and most widely spoken lingua franca is English, which was the language of Colonial Nigeria. Nigerian Pidgin – an English-based creole – is spoken by over 60 million people.

A post-creole continuum is a dialect continuum of varieties of a creole language between those most and least similar to the superstrate language. Due to social, political, and economic factors, a creole language can decreolize towards one of the languages from which it is descended, aligning its morphology, phonology, and syntax to the local standard of the dominant language but to different degrees depending on a speaker's status.

World Englishes is a term for emerging localised or indigenised varieties of English, especially varieties that have developed in territories influenced by the United Kingdom or the United States. The study of World Englishes consists of identifying varieties of English used in diverse sociolinguistic contexts globally and analyzing how sociolinguistic histories, multicultural backgrounds and contexts of function influence the use of English in different regions of the world.

In sociolinguistics, digraphia refers to the use of more than one writing system for the same language. Synchronic digraphia is the coexistence of two or more writing systems for the same language, while diachronic digraphia is the replacement of one writing system by another for a particular language.

Nigerian English, also known as Nigerian Standard English, is a dialect of English spoken in Nigeria. Based on British English, the dialect contains various loanwords and collocations from the native languages of Nigeria, due to the need to express concepts specific to the cultures of ethnic groups in the nation.

Ghanaian English is a variety of English spoken in Ghana. English is the official language of Ghana, and is used as a lingua franca throughout the country. English remains the designated language for all official and formal purposes even as there are 11 indigenous government-sponsored languages used widely throughout the country.

References

- ↑ Ghanaian Pidgin English at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Huber, Magnus (1 January 1999). Ghanaian Pidgin English in its West African Context. Varieties of English Around the World. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. doi:10.1075/veaw.g24. ISBN 978-90-272-4882-4.

- ↑ McArthur, Tom (23 April 1998). The English Languages (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9780511621048.008. ISBN 978-0-521-48130-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Amoako, Joe K.Y.B. (1992). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: In Search of Synchronic, Diachronic, and Sociolinguistic Evidence" (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Florida at Gainesville.

- 1 2 Dako, Kari (24 February 2004). "Student Pidgin (SP): the Language of the Educated Male Elite". Research Review of the Institute of African Studies. 18 (2): 53–62. doi:10.4314/rrias.v18i2.22862. ISSN 0855-4412. S2CID 146536980.

- ↑ Yakpo, Kofi (1 January 2016). ""The only language we speak really well": the English creoles of Equatorial Guinea and West Africa at the intersection of language ideologies and language policies". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2016 (239). doi:10.1515/ijsl-2016-0010. ISSN 0165-2516. S2CID 147057342.

- ↑ Huber, Magnus (19 December 2008). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: Morphology and Syntax". In Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Vol. 2. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 866–878. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-123. ISBN 978-3-11-019718-1. S2CID 241854285.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Huber, Magnus (1 January 1995). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: An Overview". English World-Wide. 16 (2): 215–249. doi:10.1075/eww.16.2.04hub. ISSN 0172-8865.

- 1 2 Huber, Magnus (2008). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: Phonology". In Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Vol. 1. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 866–873. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-053. S2CID 243085546.

- 1 2 3 4 Ewusi, Kelly Jo Trennepohl (2015). "Communicational Strategies in Ghanaian Pidgin English: Turn-Taking, Overlap and Repair" (Ph.D. Dissertation). Indiana University.

- ↑ Amoako, Joe (2011). Ghanaian Pidgin English: Diachronic, Synchronic and Sociolinguistic Perspectives. New York: Novinka. ISBN 978-1-5361-1284-9.

- ↑ Huber (1999), p. 150.

- ↑ Huber, Magnus (1999). Ghanaian Pidgin English in its West African context: A Sociohistorical and Structural Analysis. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-55619-722-2.

- ↑ Michaelis, Susanne; Philippe Maurer; Martin Haspelmath; Magnus Huber, eds. (2013). The atlas of Pidgin and Creole language structures. [Oxford], United Kingdom: APiCS Consortium. ISBN 978-0-19-969139-5. OCLC 839396764 . Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ flashfictiongh (8 April 2016). "'Ebi Time' by Fui Can-Tamakloe". Flash Fiction GHANA. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- 1 2 Huber, Magnus (1 January 1995). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: An Overview". English World-Wide. 16 (2): 215–249. doi:10.1075/eww.16.2.04hub. ISSN 0172-8865.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Amoako, Joe K.Y.B. (1992). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: In Search of Synchronic, Diachronic, and Sociolinguistic Evidence" (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Florida at Gainesville.

- ↑ McArthur, Tom (23 April 1998). The English Languages (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9780511621048.008. ISBN 978-0-521-48130-4.

- ↑ Naro, Anthony (1978). "A Study on the Origins of Pidginization". Language. 54 (2): 314–347. doi:10.2307/412950. JSTOR 412950.

- ↑ Huber, Magnus (2008). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: Phonology". In Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Vol. 1. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 866–873. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-053. S2CID 243085546.

- ↑ Ewusi, Kelly Jo Trennepohl (2015). "Communicational Strategies in Ghanaian Pidgin English: Turn-Taking, Overlap and Repair" (Ph.D. Dissertation). Indiana University.

- ↑ McArthur, Tom (1998). The English Languages. p. 164.

- ↑ Dako, Kari (24 February 2004). "Student Pidgin (SP): the Language of the Educated Male Elite". Research Review of the Institute of African Studies. 18 (2): 53–62. doi:10.4314/rrias.v18i2.22862. ISSN 0855-4412. S2CID 146536980.

- ↑ Criper, Lindsay (1971). "A Classification of Types of English in Ghana". Journal of African Languages. 10: 6–17.

- ↑ Amoako, Joe K.Y.B. (1992). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: In Search of Synchronic, Diachronic, and Sociolinguistic Evidence" (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Florida at Gainesville.

- 1 2 Amoako, Joe K.Y.B. (1992). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: In Search of Synchronic, Diachronic, and Sociolinguistic Evidence" (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Florida at Gainesville.

- ↑ Huber, Magnus (2008). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: Phonology". In Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Vol. 1. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 866–873. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-053. S2CID 243085546.

- 1 2 3 Amoako, Joe K.Y.B. (1992). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: In Search of Synchronic, Diachronic, and Sociolinguistic Evidence" (Ph.D. Dissertation). University of Florida at Gainesville.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Huber, Magnus (19 December 2008). "Ghanaian Pidgin English: Morphology and Syntax". In Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. Vol. 2. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 866–878. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-123. ISBN 978-3-11-019718-1. S2CID 241854285.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Huber, Magnus (1 January 1999). Ghanaian Pidgin English in its West African Context. Varieties of English Around the World. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. doi:10.1075/veaw.g24. ISBN 978-90-272-4882-4.

- ↑ Ewusi, Kelly Jo Trennepohl (2015). "Communicational Strategies in Ghanaian Pidgin English: Turn-Taking, Overlap and Repair" (Ph.D. Dissertation). Indiana University.

- Edgar W. Schneider, Bernd Kortmann (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: a multimedia reference tool (XVII, 1226 S. ed.). Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 866–73. ISBN 3110175320.

- Huber, Magnus (1999). Ghanaian Pidgin English in its West African Context: a sociohistorical and structural analysis. John Benjamins. ISBN 9027248826.