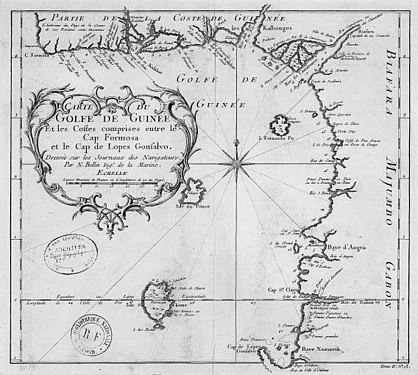

The Armed Forces of São Tomé and Príncipe are the armed forces of the island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe, off the coast of West Africa. The islands' military consists of a small land and naval contingent, with a limited budget. Sitting adjacent to strategically important sea lane of communication in the Gulf of Guinea, due to recent concerns about regional security issues including security for oil tankers transiting the area, the US military and other foreign navies have increased their engagement with the FASTP, providing the country with assistance in the form of construction projects and training missions, as well as integration into international information and intelligence sharing programs.

Annobón is a province of Equatorial Guinea. The province consists of the island of Annobón and its associated islets in the Gulf of Guinea. Annobón is the smallest province of Equatorial Guinea in both area and population. According to the 2015 census, Annobón had 5,314 inhabitants, a small population increase from the 5,008 registered by the 2001 census. The official language is Spanish but most of the inhabitants speak a creole form of Portuguese. The island's main industries are fishing and forestry.

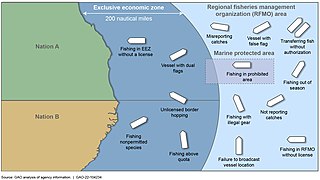

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) is an issue around the world. Fishing industry observers believe IUU occurs in most fisheries, and accounts for up to 30% of total catches in some important fisheries.

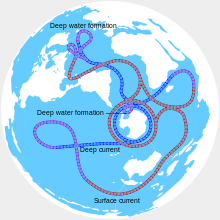

Maritime security is an umbrella term informed to classify issues in the maritime domain that are often related to national security, marine environment, economic development, and human security. This includes the world's oceans but also regional seas, territorial waters, rivers and ports, where seas act as a “stage for geopolitical power projection, interstate warfare or militarized disputes, as a source of specific threats such as piracy, or as a connector between states that enables various phenomena from colonialism to globalization”. The theoretical concept of maritime security has evolved from a narrow perspective of national naval power projection towards a buzzword that incorporates many interconnected sub-fields. The definition of the term maritime security varies and while no internationally agreed definition exists, the term has often been used to describe both existing, and new regional and international challenges to the maritime domain. The buzzword character enables international actors to discuss these new challenges without the need to define every potentially contested aspect of it. Maritime security is of increasing concern to the global shipping industry, where there are a wide range of security threats and challenges. Some of the practical issues clustered under the term of maritime security include crimes such as piracy, armed robbery at sea, trafficking of people and illicit goods, illegal fishing or marine pollution. War, warlike activity, maritime terrorism and interstate rivalry are also maritime security concerns.

Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea affects a number of countries in West Africa as well as the wider international community. By 2011, it had become an issue of global concern. Pirates in the Gulf of Guinea are often part of heavily armed criminal enterprises, who employ violent methods to steal oil cargo. In 2012, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), Oceans Beyond Piracy and the Maritime Piracy Humanitarian Response Program reported that the number of vessels attacks by West African pirates had reached a world high, with 966 seafarers attacked during the year. According to the Control Risks Group, pirate attacks in the Gulf of Guinea had by mid-November 2013 maintained a steady level of around 100 attempted hijackings in the year, a close second behind the Strait of Malacca in Southeast Asia.

Africa Partnership Station is an international initiative developed by United States Naval Forces Europe-Africa, which works cooperatively with U.S. and international partners to improve maritime safety and security in Africa as part of US Africa Command's Security Cooperation program.

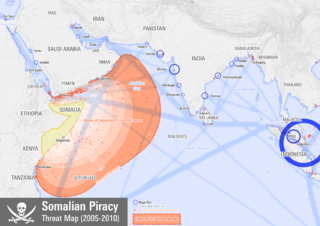

Piracy off the coast of Somalia occurs in the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel, and Somali Sea, in Somali territorial waters and other surrounding places and has a long troubled history with different perspectives from different communities. It was initially a threat to international fishing vessels during the early 2000s, only to rapidly escalate and expand to international shipping during the War in Somalia (2006–2009).

Piracy in the 21st century has taken place in a number of waters around the world, including the Gulf of Guinea, Strait of Malacca, Sulu and Celebes Seas, Indian Ocean, and Falcon Lake.

Abshir Abdillahi, known as "Boyah" is a Somali pirate.

Piracy in Somalia has been a threat to international shipping since the beginning of the country's civil war in the early 1990s. Since 2005, many international organizations have expressed concern over the rise in acts of piracy. Piracy impeded the delivery of shipments and increased shipping expenses, costing an estimated $6.6 to $6.9 billion a year in global trade in 2011 according to Oceans Beyond Piracy (OBP).

The Directorate General of Marine and Fisheries Resources Surveillance is a government agency under the management of the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of Indonesia. Formally established on 23 November 2000 according to Presidential Decree No. 165/2000, the PSDKP is the agency responsible for supervising the marine and fishery resources of the Republic of Indonesia. The main mission of PSDKP is the prevention of Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in Indonesian waters, which has caused a substantial loss for Indonesia's fishing industry. In its mission to prevent illegal fishing, PSDKP has conducted joint-operations with the Indonesian Navy, Water Police, Sea and Coast Guard, the Maritime Security Agency and Customs. PSDKP is however is not associated with these agencies.

Piracy off the coast of Venezuela increased during the crisis in Venezuela. The situation has been compared to piracy off the coast of Somalia, which was also caused by economic collapse. As Venezuelans grow more desperate, fears of increasing incidents and range of piracy have been reported. Venezuelan pirates often smuggle weapons, drugs and sex trafficking victims. Authorities have also been involved in piracy near the coast of Venezuela.

Transshipment or transhipment at sea is done by transferring goods such as cargo, personnel, and equipment from one ship to another. It is a common practice in global fisheries and typically takes place between smaller fishing vessels and large specialized refrigerated transport vessels, also referred to as “reefers” that onload catch and deliver supplies if necessary.

As a practice of piracy, petro-piracy, also sometimes called oil piracy or petrol piracy, is defined as “illegal taking of oil after vessel hijacks, which are sometimes executed with the use of motorships” with huge potential financial rewards. Petro-piracy is mostly a practice that is connected to and originates from piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, but examples of petro-piracy outside of the Gulf of Guinea is not uncommon. At least since 2008, the Gulf of Guinea has been home to pirates practicing petro-piracy by targeting the region's extensive oil industry. Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea has risen in the last years to become the hot spot of piracy globally with 76 actual and attempted attacks, according to the International Maritime Bureau (IMB). Most of these attacks in the Gulf of Guinea take place in inland or territorial waters, but recently pirates have been proven to venture further out to sea, e.g. crew members were kidnapped from the tanker David B. 220 nautical miles outside of Benin. Pirates most often targets vessels carrying oil products and kidnappings of crew for ransom. IMB reports that countries in the Gulf of Guinea, Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Togo, Congo, and, especially, Nigeria, have experienced petro-piracy and kidnappings of crew as the most common trends of piracy attacks in the Gulf of Guinea.

Piracy kidnappings occur during piracy, when people are kidnapped by pirates or taken hostage. Article 1 of the United Nations International Convention against the Taking of Hostages defines a hostage-taker as "any person who seizes or detains and threatens to kill, to injure, or to continue to detain another person in order to compel a third party namely, a State, an international intergovernmental organization, a natural or Juridical person, or a group of people, to do or abstain from doing any act as an explicit or implicit condition tor the release of the hostage commits the offense of taking of hostages ("hostage-taking") within the meaning of this convention." Kidnappers often try to obtain the largest financial reward possible in exchange for hostages, but piracy kidnappings can also be politically motivated.

The European Union is one of the main anti-piracy actors in the Gulf of Guinea (GoG). At any one time, the EU has on average 30 owned or flagged vessels in the region. The piracy in the Gulf of Guinea is therefore a threat towards the EU, and as a response the organization adopted its strategy on the Gulf of Guinea in March 2014. The Strategy on the Gulf of Guinea is a 12-page document with the scope of the problem, what have previously been done, responses and the way forward with four strategic objectives. The EU's overriding objective are:

- to build a common understanding in regional countries of the threat and its long-term effect and the need to address the piracy issues among the regional and international community.

- to help the governments in the region to ensure maritime awareness, security and the rule of law by building robust institutions and maritime administrations.

- to assist vulnerable economies to withstand criminal or violent activity and to build resilience to communities.

- to strengthen cooperation between the countries and organizations on the region to fight threats both on land and sea.

Piracy network in Nigeria refers to the organisation of actors involved in the sophisticated, complex piracy activities: piracy kidnappings and petro-piracy. The most organised piracy activities in the Gulf of Guinea takes place in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. A large number of both non-state and formal state actors are involved in a piracy operation, indicating a vast social network. As revealed by the arrested pirate Bless Nube “we do not work in isolation. We have a network of ministries’ workers. What they do is to give us information on the location and content of the vessels to be hijacked. After furnishing us with the information, they would make part payment, and after the hijack, they would pay us the balance.” Pirate groups draw on the pirate network to gain access to actors who provide security, economic resources, and support to pirate operations. This includes government officials, businesspeople, armed groups, and transnational mafia.

Seychelles is a small island nation with a vast maritime territory, consisting of 115 islands and a 137 million square kilometer Exclusive Economic Zone. The prevalence of drugs in the country is high and the country is experiencing a heroin epidemic, with an equivalent to 10% of the working force using heroin in 2019. Due to its location along a major trafficking route, drugs can easily be trafficked by sea to Seychelles.

The Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) is a regional maritime security centre hosted by the Indian Navy. Launched in December 2018, the centre works towards enhancing maritime security and safety in the Indian Ocean. Currently, the IFC-IOR has International Liaison Officers (ILO) from 12 partner nations. It also has more than 65 international working-level linkages with nations and multi-national/ maritime security centres.

Fisheries crime describes the wide range of criminal activity that is common along the entire value chain of the fishing sector. It often occurs in conjunction with Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU), but next to illegal fish extraction include for example corruption, document fraud, tax evasion, money laundering, kidnapping, human trafficking and drug trafficking. The issue recently received increased attention in the UN, Interpol, and several other international bodies.